On January 4, 1961, Theotis Robinson Jr. arrived on campus as an undergraduate student. It was his application and subsequent meetings with UT administrators, including President Andy Holt, that led to the change in the admissions policy that barred Black undergraduate students. Two other African American students joined him. “I had a sense of excitement,” Robinson recalls, “and a sense of being not quite sure what it was going to be like and what the reception was going to be.”

Robinson had grown up on Houston Street, two blocks from the all-white East High School. His parents, Alma and Theotis Sr., operated Five Points Restaurant at that storied East Knoxville intersection. After graduating from Austin High School in 1960, Robinson had taken part in sit-ins to integrate the lunch counters at stores like S. H. Kress, Woolworth’s, Miller’s, Cole’s Drugstore, W. T. Grant, McClellan’s, and Rich’s, which had a white lunch counter on its main floor and a black lunch counter in the basement. Through June and into July, the sit-ins continued. Some stores closed their lunch counters “for renovation.” Others announced they were closing them permanently.

On July 10, amid the furor, the Associated Council for Full Citizenship, which had organized the sit-ins, ran a quarter-page ad in the Sunday Knoxville News Sentinel titled “An Appeal for Human Rights,” listing 16 areas in which Black people in Knoxville were discriminated against. One was the university, whose undergraduate program did not admit Black people. “I said to myself, ‘This is something I can do something about.’”

UT had admitted four African Americans to its graduate and law programs in 1952. In 1955, the Board of Trustees voted to adopt a plan by the state Board of Education that would have desegregated all UT undergraduate and graduate programs, but this was met with a backlash by segregationists. In 1956, the state Supreme Court ruled that all state laws on segregation were invalid, but UT had made no move to integrate.

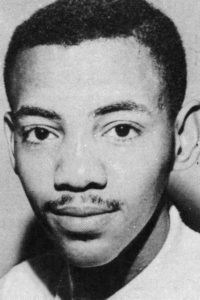

Theotis Robinson Jr., Charles Blair, and Willie Mae Gillespie were UT’s first admitted black undergraduates in January 1961.

“I sat down that evening at the family kitchen table and wrote a letter requesting admission,” says Robinson, who avoided any mention of race, his segregated high school, or other indicators that might reveal him to be Black. His return address was on the envelope, but his area of Houston Street had both white and Black residents. Robinson had a scholarship to historically Black Knoxville College. He wanted to major in political science, but a major in that discipline was not offered, so he requested admission to UT. He felt it was his right as a taxpayer, and, like other young Knoxvillians, he had an affinity for the university. In the early 1950s his father had been a cook for the athletes’ training table under the East stands of Shields-Watkins Field. His benefits included two tickets to football games, so father and son watched the games, albeit from a segregated section on the north end of the West stands.

“I’m one of the few people who can honestly say they saw Jim Haslam play football,” says Robinson with a chuckle. “I mention that to him every time I see him.”

On July 18, 1960, seven downtown lunch counters were opened to all customers without incident, turning the tide toward desegregation. But the university continued to stick with Jim Crow.

“I got a letter back from UT saying it was sorry, but the university would not accept ‘Negroes’ to the undergraduate school,” Robinson remembers. “I don’t know exactly how they did their checking, but they obviously ran a check and determined who I was.”

Robinson and his parents met with the two deans of graduate and undergraduate admissions, who had signed the rejection letter, and later with President Andy Holt to discuss the application. All the administrators said they could not admit Robinson unless the Board of Trustees allowed it. Holt asked if the Robinsons wanted him to take the matter to the board. They said yes. He then said that he could not guarantee what decision the board would make. Robinson and his parents said they understood. Young Robinson then said that if the board did not change its policy, the family would sue the university.

Holt agreed to present the matter to the board.

The board requested that the state attorney general attend its November meeting to discuss the matter. He was told that Robinson met the admissions requirements but asked if he thought he could win a lawsuit challenging the policy of segregation in the undergraduate school. He responded that given the precedents being established by the courts, he did not have a defense of the system of segregation that could prevail.

After learning that the university was likely to lose such a lawsuit, the board voted to admit African American undergraduates. And so a new era began for UT in January of 1961.

“I had that sense of not quite apprehension, but looking forward to this experience,” says Robinson. “I had never gone to school with white people. I knew a few white students who had taken part in the sit-ins, but that was it. It was peaceful, as compared to the University of Georgia five days later. When they admitted two Black transfer students, a riot broke out and a dorm was torched.”

As a married commuter student, Robinson was typically on campus during the day; after school he went to work for his parents at Five Points then returned home to study. His early days at UT were, on the whole, what he expected. There were racist students and professors, and there were friendlier ones. There were incidents that made him feel unwelcome, and there were some that gave him a sense of camaraderie with his fellow students. Playing basketball with football star Mike Lucci serves as an example.

Robinson became involved in civil rights demonstrations on campus and in the Knoxville community. He also became involved in campus politics, planning the elections of Black students for Student Government Association offices.

After leaving the university, Robinson went on to become the first African American in more than 50 years elected to the Knoxville City Council, where he served through 1977. He also served as vice president for economic development for the 1982 World’s Fair.

“It was an exhilarating time,” he remembers. “There was no template for what we were doing or certainly for what I was doing. I was advocating for Black inclusion in every aspect of the fair.”

This turned out to be smart marketing. “We had large Black attendance, and we made money. Other fairs that did not reach out to Black attendees lost their shirts.” Robinson taught a class in political science in 1989 and has often served as a guest lecturer at UT. He worked in the purchasing department and later became special projects coordinator in the Office of Government Relations. In 2000, he was named vice president for equity and diversity for the UT System. He held that position until his retirement in 2014.

He is also a regular contributor to editorial pages as a freelance columnist for the Knoxville News Sentinel (USA Today Network). At the September Alumni Awards Gala, Robinson was honored as a Distinguished Alumnus. The UT Board of Trustees, at its June 2019 meeting, granted Robinson an honorary doctorate from the College of Social Work. The degree was presented during commencement exercises in December.

“UT has come a long way,” he says, “and UT has a long way to go. Enrollment needs to reflect the diversity of the state. The Black population of Tennessee is roughly 14 percent. The Latino population is rising. Corporations want a diverse workforce. The university needs to be training a diverse workforce.”

This story is part of the University of Tennessee’s 225th anniversary celebration. Volunteers light the way for others across Tennessee and throughout the world.

This story is part of the University of Tennessee’s 225th anniversary celebration. Volunteers light the way for others across Tennessee and throughout the world.

Learn more about UT’s 225th anniversary