Coming down Hall of Fame Drive in Knoxville, Tennessee, it’s hard to miss the mammoth orange basketball and hoop connected to a large white building. This is the Women’s Basketball Hall of Fame, celebrating the trailblazers, pioneers, and champions who have made up the sport—including many who played the game in Knoxville and a few who changed it for future generations.

Honoring the Past

The spirit of the hall’s motto—“Honor the past, celebrate the present, and promote the future”—is woven through exhibits that show the evolution of the game. One display shows the birth of women’s basketball, when the players shared a janitor’s closet with a damp mop and bucket. This was their locker room in 1892, a few months after the game was invented.

Women originally played 3-on-3 on a half-court setting. A copy of the original Spalding women’s rule book can be found in the museum, the pages tattered and yellowed from age, alongside a pair of the first women’s basketball shoes. They could be mistaken for old Converse high-tops at first glance—black with a white sole and laces and a white circular emblem on the ankle.

Some early uniforms hang nearby, including one that belonged to a woman who played for Cook’s Goldblume, a Nashville brewery. The shorts are silky royal blue with yellow stripes on the side and the hem, and the shirt is mustard yellow with royal blue accents.

Around the corner from the first uniforms, visitors hear a distinct voice fill the room. The late Pat Summitt—a larger-than-life hero in college basketball—is heard from a mockup of a contemporary locker room. Two benches, each with two player mannequins, sit in front of a screen where Summitt is giving one of her infamous speeches. The lockers represent how far the professional sphere for women has changed. On the far left hang three uniforms from the Women’s National Basketball Association. In the middle is a Team USA jersey with three basketballs underneath it. The far right showcases broadcasting, with ESPNU and ESPNW represented. The common denominator in all three showcases is Summitt.

Pat Summitt coaches during a game at Thompson-Boling Arena in Knoxville. Photo by Tennessee Athletics

Kelly Mathis, director of development at the Hall of Fame, says this is her favorite exhibit. “I listen to the way they communicate and inspire,” Mathis says. “I think that’s the key to coaching—not just in athletics but the key to coaching anybody in anything.”

Summitt had a huge voice, on and off the court. Early in her coaching career at the University of Tennessee she helped pave the way for high school girls in the state to play under the same full-court rules as boys, and she remained a strong advocate for the principle that women players deserve equal opportunity and the same funding as their male counterparts. In turn, her players fought for her on the court. Summitt led her Lady Vols to eight NCAA championships, including three in a row from 1996 to 1998.

Gloria Scott Deathridge was the first Black Lady Vol basketball player. She remembers walking to class and seeing an ad on a telephone pole wanting women to try out for the Lady Volunteers. Deathridge took that opportunity and made her way down to Alumni Memorial Gym, a space on campus that has since been remodeled into lecture halls.

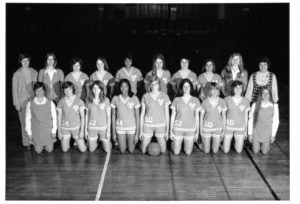

1973–74 Lady Vols. No. 44 Gloria Scott Deathridge is in the front row, fourth from left.

“I remember when Title IX was passed in 1972,” says Deathridge of the law that prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex in education programs and activities. “I also remember when Pat Head Summitt was determined to make us go five-on-five.”

Joan Cronan, now UT’s women’s athletic director emerita, started her career in 1973, just a year after the passing of Title IX. She met with Ted Stern, president of the College of Charleston, to express to him

the importance of Title IX and what it would mean for women years down the road. She left that meeting with four jobs: volleyball, basketball, and tennis coach and women’s athletics director. She left Charleston for UT in 1983.

“I knew at 12 I wanted to be in the business of basketball,” Cronan says. “And they did not have any opportunities for women.”

For Cronan, Title IX means women have the same equal opportunities as men do in sports. “The University of Tennessee did the most to help women in the world of athletics,” she says.

In the early days following the passage of Title IX, women’s athletics still did not have the same budgets or opportunities as men. Women’s teams often had to travel in station wagons while the men’s teams traveled in buses. “We raised money by selling doughnuts,” remembers Deathridge, “so we would have the money to go places.”

Head Coach Pat Summitt and Joan Cronan during the celebration of Summitt’s 1,000th win.

With UT and Summitt, women no longer had a glass ceiling to break. The world was realizing that women were just as competitive as men—and sometimes even better.

Celebrating the Present

Around the corner in the Hall of Fame, a display of jerseys celebrates the women’s Final Four teams from the 2022 NCAA tournament—South Carolina, Connecticut, Louisville, and Stanford. South Carolina defeated UConn 64–49 in the national championship game. The cases include warmup gear for each team as well as jerseys, shoes, mascots, and other school symbols.

With the passing of Title IX, the landscape of women’s sports exploded. The first women’s professional league was the Women’s Professional Basketball League, which had its inaugural season in 1978 with eight teams. The league grew to 14 teams before disbanding in 1981.

In 1982, the first women’s Final Four was played in Norfolk, Virginia. The teams were Louisiana Tech, UT, Cheyney, and Maryland. Louisiana Tech defeated Maryland 76–62 to become the first women’s basketball national champions.

Summitt, who coached that 1982 Lady Vols team, would go on to appear in 18 other Final Fours before retiring in 2012 following a diagnosis of early onset Alzheimer’s disease.

During Summitt’s tenure, she coached some of the greatest athletes in the history of women’s basketball, including Candace Parker, Tamika Catchings, Chamique Holdsclaw, and Kellie Jolly Harper.

Harper was with Summitt for the Lady Vols’ legendary three-peat in 1996 through 1998. She went on to the WNBA, playing for the Cleveland Rockers in 1999. In 2000, she began her coaching career with stops at Auburn, UT Chattanooga, and Missouri State, among others, before returning to her alma mater in 2019.

Forward Karoline Striplin, No. 11 of the Tennessee Lady Vols. Photo by Ian Cox/Tennessee Athletics

Karoline Striplin, now a sophomore forward for the Lady Vols, grew up around sports in Hartford, Alabama. Both of her parents played sports, and her father is the women’s basketball coach at her high school.

“You would always hear her name,” Striplin says of Summitt. “She’s the GOAT.”

Striplin has known only the opportunities and landscape of the current environment of women’s basketball, and she is inspired by those who fought for her opportunity to play. She recalls hearing about the hardships that women before her had to endure and is thankful for the freedom she has to play the sport she loves.

“As a player, Title IX really encourages me,” Striplin says. “Women getting the equal opportunity as men is something that we don’t want to take for granted.”

The theme of “Celebrating the Present” continues throughout the museum, taking up most of the space. The most prominent feature is the Ring of Honor, with more than 100 jerseys that hang from the rafter of the back rotunda in the museum representing the current high school Gatorade State Players of the Year and collegiate All-Americans—some of the nation’s finest young players and the future of the sport.

Promoting the Future

The Women’s Basketball Hall of Fame plays a prominent role in the community. Mathis’s passion is to educate young women who may not know about Title IX by embracing what she calls the three Es: educate, engage, and empower.

The hall honors the trailblazers who paved the way for the present and future hall of famers at its annual induction ceremony, which takes place each spring.

The Hall of Fame’s goal is to keep the stories of women’s basketball alive. For 2023, the Hall of Fame is putting together leadership programs. Mathis is working to gather donors and sponsors. “I’m really pushing for a H.E.R. Academy—H.E.R. being an acronym for health, empowerment, and respect,” she says.

The Hall of Fame wants to reach current and future players at all economic levels, especially girls who are in foster care. “We want to create an environment that is consistent for them and inspires them,” Mathis says.

The hall hosts an annual tournament called the Ladies Ball for teams that are selected by region in divisions ranging from fourth and fifth grades through ninth grade. Girls not only experience the tournament but are also educated on women’s basketball.

“We want to give the youth the best experience, because they should love playing and being around their friends instead of competing for a scholarship.”

—

Women’s Basketball Hall of Fame image by Steven Bearden

Other photos courtesy of Tennessee Athletics

4 comments

Awesome article. Gloria Deathridge truly embodies the Volunteer Sprit and Leadership!

A correction: The 2022 NCAA Women’s Championship featured South Carolina defeating Louisville in the Semifinal. South Carolina then defeated UConn in the finals, 64-49. This was particularly notable because it was the first time Geno Auriemma lost in the finals out of 11 appearances.

Thanks for the correction! It has been changed in the article.

Best,

Cassandra Sproles

Executive Editor

thx