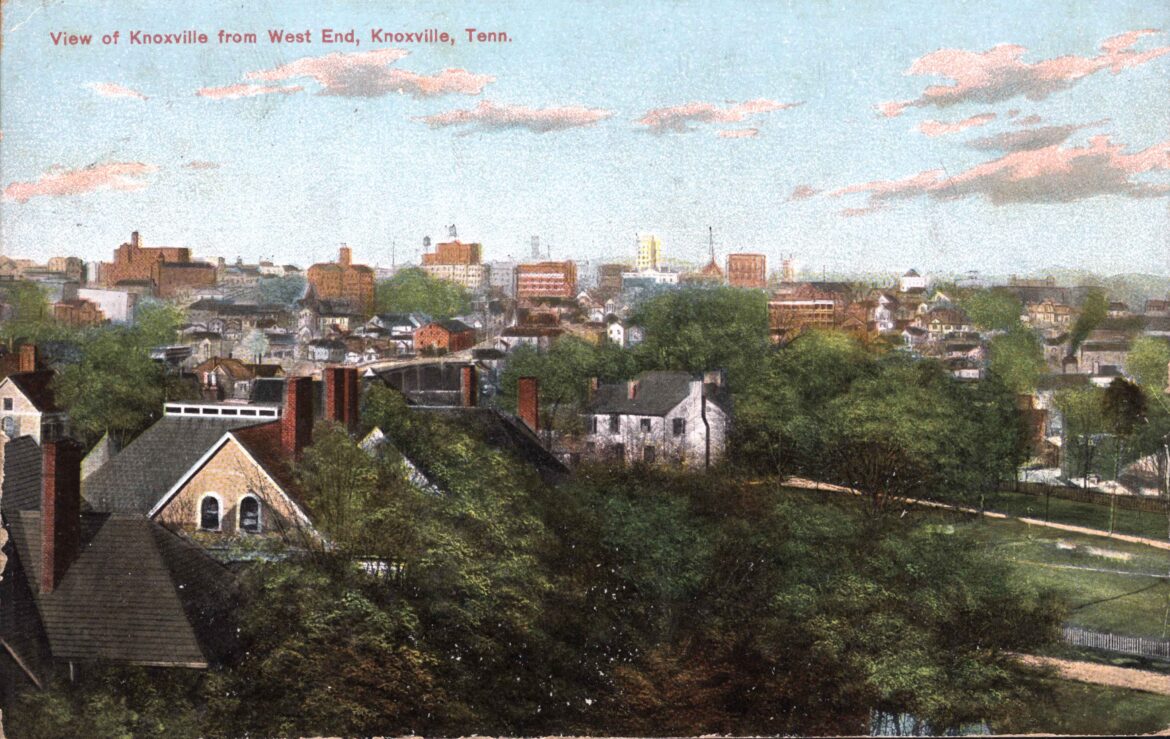

In Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, a father and son walk through a post-apocalyptic landscape that, to Knoxville readers, could resemble the Henley Street Bridge and Chapman Highway. They stop at the father’s decaying boyhood home, finding the nail holes in the mantel where they hung Christmas stockings, then walk down the highway toward the mountains. Was it the McCarthy family’s home on Martin Mill Pike? “Yes, that was it,” confirmed Dennis McCarthy, Cormac’s youngest brother, in an impromptu conversation at Kroger not long after the book came out in 2006. “As a matter of fact,” he added, “that house burned down just a couple of weeks ago.”

It was suggested that this was a terrible loss to Knoxville’s literary legacy, akin to the razing of James Agee’s boyhood home in Fort Sanders. “Nah,” he said. “That house was pretty well gone.”

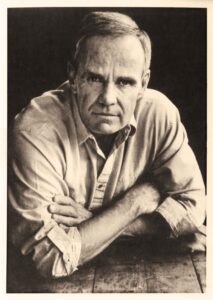

McCarthy’s 11th and 12th novels, The Passenger and Stella Maris, were released in late 2022, and he died at age 89 a few months later on June 13, 2023. With those events “the McCarthy discourse has changed,” says UT Professor of English Bill Hardwig, who teaches courses on McCarthy and is working on a book, How Cormac Works: McCarthy, Language, and Style.

“McCarthy hadn’t published any fiction since 2006 and The Road, so he wasn’t in the minds of many readers and scholars. It’s led to the re-evaluation of his six-decade career and the very public acknowledgment of just how accomplished and important a writer he was.”

Prominent regional references in The Passenger and Stella Maris—to Oak Ridge during the Manhattan Project and homes inundated by Tennessee Valley Authority dams—reopened the discourse on the importance of Knoxville and its environs in McCarthy’s first four novels. “So many of his pictures of the city are not terribly flattering,” says Hardwig. “Down and out people, people at the margins. Once Knoxville got used to being the Scruffy City, it was easier to celebrate McCarthy.”

A character in The Passenger asks, “Does Knoxville produce crazy people, or does it just attract them?” Another replies, “Interesting question. Nature, nurture. Actually, the more deranged of them seem to hail from the neighboring hinterlands. Good question though. Let me get back to you on that.”

McCarthy’s Time in Knoxville and at UT

McCarthy was born in Rhode Island and moved with his family to Knoxville in 1937, when his father took a job as a TVA lawyer. He attended St. Mary’s Parochial School, near the Church of the Immaculate Conception on Summit Hill, and Knox Catholic High, then in a Magnolia Avenue mansion. He attended UT from 1951 to 1952, left to serve in the Air Force, and returned in 1957. McCarthy’s love of writing was sparked by a project repunctuating 18th-century manuscripts for a textbook.

“He loved his creative writing classes and his English classes,” says Hardwig. McCarthy’s first short stories were published in the first two issues of UT’s Phoenix literary magazine, which longtime English Professor John C. Hodges founded in 1959.

McCarthy won two creative writing awards but did not graduate from UT; he was short a course or two.

In the summer of 1959, he began writing his first novel, The Orchard Keeper, about a moonshine runner in neighboring Sevier County who at one point gets some bad gas, stalls out on the Gay Street Bridge, and is arrested. “He was strongly influenced by Faulkner,” notes Hardwig.

McCarthy began writing Suttree in May 1962. It took 17 years and became his fourth novel. In the interim came Outer Dark (1968), taking place in Appalachia at the turn of the 20th century, and Child of God (1973) built on horrific real events in Sevier County.

“It’s graphic, violent, disturbing,” says Hardwig, “and a little less like Faulkner. In finding his voice, he was paying attention to the people and voices of East Tennessee. He was writing words the way he heard them in his head.” This accounts, in part, for McCarthy’s habit of avoiding commas and apostrophes.

Hardwig and McCarthy

Hardwig grew up in Knoxville and earned his BA at UT in 1991, but he didn’t encounter McCarthy’s work until the summer between years of working on his master’s at the University of Illinois at Chicago. He was temping in an office on the 72nd floor of what is now the Aon Center and read All the Pretty Horses during his lunch breaks.

McCarthy did not come up in Hardwig’s PhD work in American literature at Florida. It wasn’t until he was teaching Appalachian literature at UT that he included one of McCarthy’s novels, Child of God, in the syllabus.

Sarah Yancey, a PhD student in medieval literature who took the course, is drawn to Child of God as a retelling of Beowulf.

“In drafts he makes notes from the Burton Raffel translation of Beowulf,” she says. “In subsequent drafts he dialed it back. I have a sneaking suspicion he interacted with Beowulf at UT and that experience resonated.”

Blood Meridian, released in 1985, was critically acclaimed but not widely read, says Hardwig. “It wasn’t until All the Pretty Horses (1992), which became a national best-seller and winner of the National Book Award, that McCarthy became a widely read and discussed author.

Even then, the movie adaptations of his fiction—notably All the Pretty Horses (2000), No Country for Old

Men (2007), and The Road (2009)—did as much as anything to make him a household name.”

Knoxville’s Portrayal in Suttree

McCarthy’s 1979 novel Suttree takes place in 1951 Knoxville. Cornelius Suttree lives in a houseboat on the river amid communities of shanties.

He sells the more desirable fish he catches on Market Square, then descends to the Old City and the segregated Black shopping district to sell the less desirable ones. “This city constructed of no known paradigm,” writes McCarthy, “a mongrel architecture reading back through the works of man in a brief delineation of the aberrant disordered and mad.”

In Suttree, Yancey again notes similarities to Beowulf—in particular, Beowulf and the thanes just before

Grendel’s attack. She also sees parallels to another Old English heroic work, The Finnesburg

Fragment.

The real-life Suttree Landing Park is in the vicinity of a spot in South Knoxville where Suttree runs a police car into the river after stealing it.

Much of the novel takes place in the neighborhood McAnally Flats, which was razed to make room for I-40. Yancey lives in nearby Old Mechanicsville. “When I read about McAnally Flats,” she says, “I know what that looks like.”

Cameron Hashmi, a recent English master’s graduate, says, “It’s wonderful to have someone reach the heights of the great modernists using Knoxville as a setting, the same as Joyce uses Dublin in Ulysses, if you look at Suttree as a psycho-geographical portrait, sort of an extended metaphor in some way. The biggest thing for me is that it has imbued the place that I live in with this magic. It gives me a heightened sensibility in the way that he describes it, giving Knoxville this almost religious significance.”

A LITERARY CORRESPONDENCE

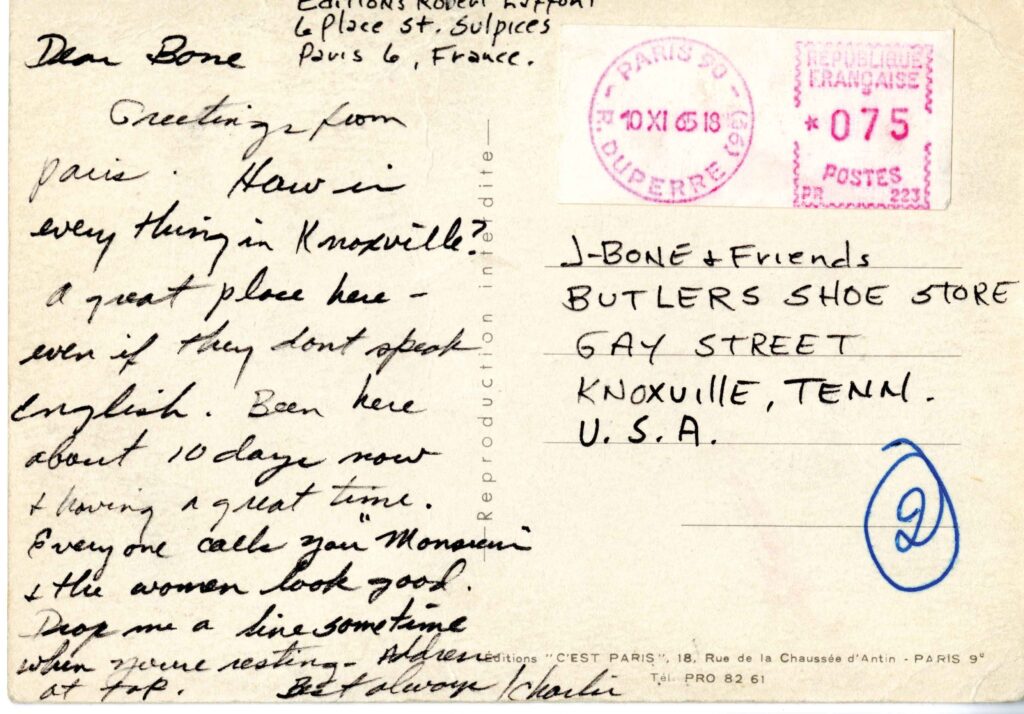

UT Libraries Special Collections has among its holdings Cormac McCarthy’s correspondence with John Fergus Ryan (1931–2003), a Memphis-based journalist, humorist, playwright, and novelist. Unlike most correspondence holdings, the collection is two-sided: in addition to 17 letters from McCarthy to Ryan, it includes carbon copies of 26 letters from Ryan to McCarthy.

The correspondence between the authors, which ranges from 1976 to 1985, begins with Ryan writing to McCarthy to introduce himself and congratulate McCarthy on his Guggenheim Award. At the beginning of the correspondence McCarthy is living in Louisville, Tennessee, just outside Knoxville. Later he writes from Knoxville; Lexington, Kentucky; El Paso, Texas; Santa Fe, New Mexico; New Orleans; and Chihuahua, Mexico.

The letters preserve the authors’ thoughts on a wide range of topics, from making a living as a writer to the various places they lived and visited to classical music. They discuss authors including Henry Miller, William S. Burroughs, and James Agee as well as the contemporary state of publishing. They provide candid insights into the lives of two Tennessee writers—one who would go on to global acclaim and the other who would attain distinction but never broad recognition.

The collection, officially titled A Literary Correspondence: Letters Between Cormac McCarthy and John Fergus Ryan, adds to the libraries’ substantial holdings of prominent writers with local and regional connections, including James Agee, Wilma Dykeman, Thomas Wolfe, Alex Haley, and David Madden.

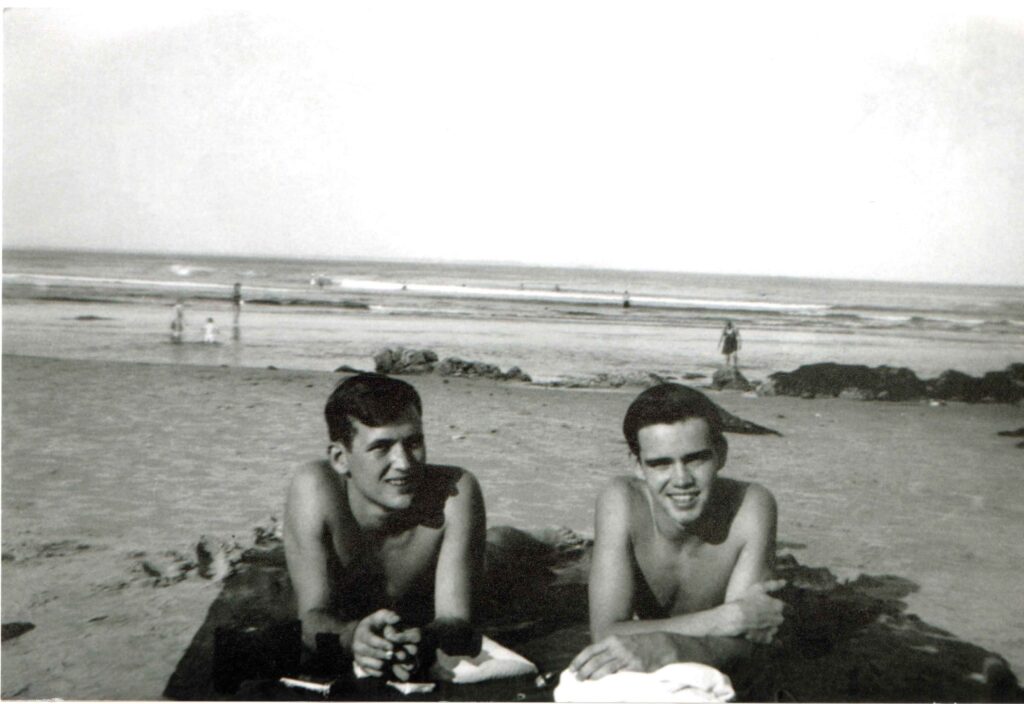

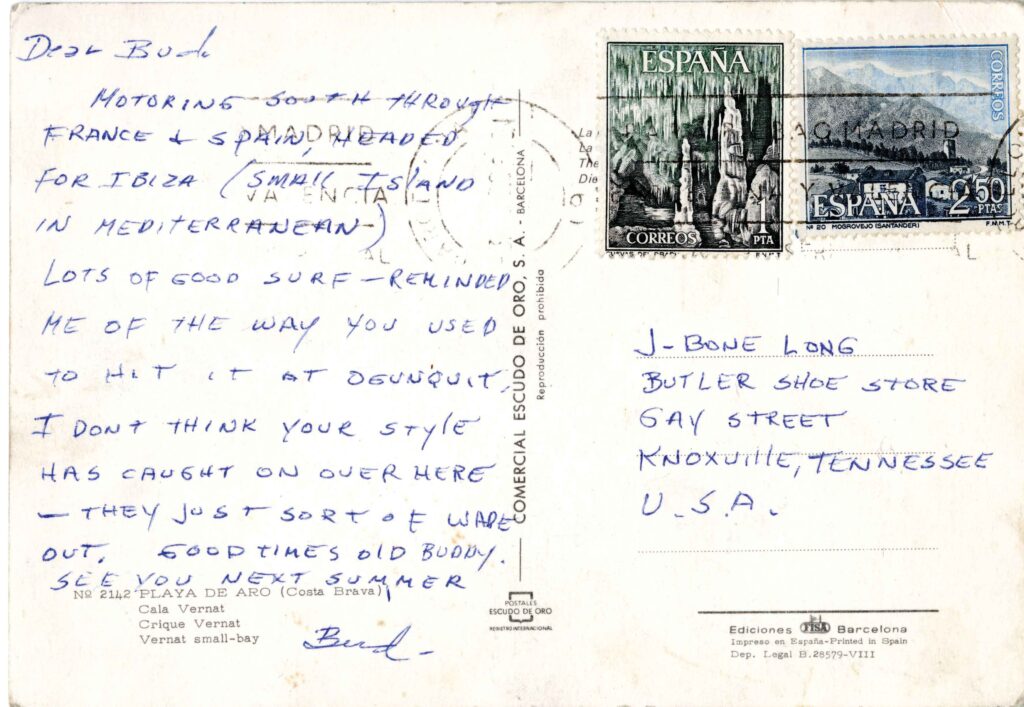

UT Libraries also recently acquired photos, letters, and postcards from the widow of Jim Long, the Knoxville man on whom McCarthy based one of his characters in Suttree. The collection includes Long’s inscribed first edition of Suttree, a photograph of McCarthy and Long on a beach in Maine, and postcards McCarthy sent from France, Ireland, Argentina, and Spain.

Images courtesy of UT Libraries Special Collections

—

Feature image courtesy of Knoxville History Project