What’s the most intellectually exciting spot in Tennessee? Thousands of professors have taught on the Hill, of course, and contributed to the tradition. But for more than a century, UT has attracted some of the great thinkers of the world to campus for a few hours or a few days. Many of them are giants of thought, known internationally, whose only visit to this region was to give an interesting lecture at UT.

William Jennings Bryan

The tradition of intellectual celebrities speaking on the Hill started before World War I. During the era of the teachers’ convention known as the Summer School of the South, Columbia philosopher–author John Dewey, Chicago reformer Jane Addams, and statesman William Jennings Bryan (during his final presidential campaign) all gave speeches to large crowds at Jefferson Hall, the large ad-hoc building that stood on the quad.

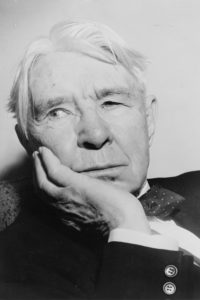

Carl Sandburg

By the 1920s, UT had enough students on its own to justify an occasional guest speaker. Carl Sandburg was already being hailed as one of America’s great poets when he spoke on the Hill (and sang and played banjo) in December 1924. And, if we can believe a newspaper report, while he was in town, Sandburg actually banged out another chapter of his famous biography Lincoln: The Prairie Years, in a newspaper office on Gay Street. Invited to a football game, he said he’d rather explore Knoxville’s Civil War sites.

It was the first of several visits. He developed longtime friendships with UT English professors Alvin Thaler and John Hodges, with whom he sometimes stayed. The Chicagoan eventually moved to Western North Carolina and was known to haunt Knoxville’s Market Square from time to time.

By 1955, a few weeks before he turned 80, a Sandburg lecture at UT was a big, public deal. He gave a memorable speech and reading at the Alumni Memorial Building, bewailing American conformity.

An impressive number of foreign scholars came to the Hill in the 1920s, most by way of an ambitious speaker initiative by English department head Charles Bell Burke, who brought in Icelandic polar explorer Vihjalmer Stefansson, British philosopher John Cowper Powys, Chinese art critic T.Y. Wang. In early 1926, Calcutta scholar M.H.H. Joachim spoke on “Gandhi and the Nationalist Movement” more than two decades before Indian independence. Borrowing a term, and perhaps a concept, from ancient Athens, Burke called his series the Lyceum.

Eleanor Roosevelt

In March 1937, just after her husband’s second inauguration, Eleanor Roosevelt gave UT’s most heralded talk of the decade at Alumni Memorial. Some people reportedly came from as much as 400 miles away to attend her talk on “The Responsibility of the Individual to His Community.” It was the last talk in her railroad speaking tour, which she narrated in her daily newspaper column.

Helen Keller

Reformer Helen Keller lectured at Alumni Memorial in November 1941, long before her story inspired the play The Miracle Worker.

Globetrotting journalist Harrison Salisbury spoke at UT in 1964, on the cusp of his early criticism of the Vietnam War. Historian and former John Kennedy aide Arthur Schlesinger spoke on “The Future of the Presidency” at Alumni Memorial in April 1966; he got to know UT pretty well, speaking here several times over his career.

Ralph Nader

Few famous speakers have returned to UT with the frequency of author and future presidential candidate Ralph Nader, who spoke at UT three times between 1966 and 1968, raising concerns about air pollution, noise pollution, and corporate greed. In 1969, Vance Packard, best known for his books on corporate manipulation of consumers, spoke at the University Center, raising alarms about consumers’ data privacy four decades before Facebook was born. Alan Guttmacher, president of Planned Parenthood, spoke at UT in 1969 on the subject of “Medicine and Social Responsibility.”

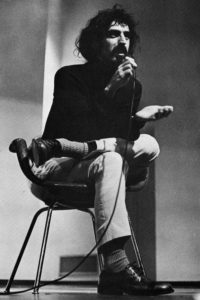

Frank Zappa

The same year, Benjamin Spock spoke, not on how to raise your children, but in opposition to the Vietnam War. Considering some assumptions of UT’s conservatism, it’s impressive how many bold speakers came to campus to talk about change. Leftist author/columnist Max Lerner was an attraction in 1968. Frank Zappa, one of the most daring musicians of his era, didn’t do a lot of speaking, but he gave it a try at UT in April 1969. An audio copy of his speech has drifted in and out of the Internet over the last several years. British filmmaker Peter Watkins, notable for his influence on John Lennon’s sudden interest in pacifist politics, spoke at UT in 1978.

A different sort of thinker of his time, Gene Roddenberry, spoke at Alumni Memorial in 1975, showing Star Trek outtakes.

Although UT was formally desegregated in 1961, event planners appear not to have been eager to include black intellectuals as speakers. UT invited Republican Edward Brooke of Massachusetts, then America’s only black US senator, to speak in early April 1968. The talk was a victim of terrible timing. Due to Martin Luther King Jr.’s funeral, Brooke canceled and apparently never rescheduled.

Civil rights speakers included NCAA chief Roy Wilkins, who in early 1969 led an interesting-sounding workshop at the University Center with civil engineers about improving conditions in the inner city. Hosea Williams, a close Martin Luther King Jr. aide and activist, spoke at the University Center in 1978.

Dick Gregory

Perhaps the most controversial speaker in UT history was black comedian—activist Dick Gregory, who was the subject of a two-year-long standoff between the student-run speaker committee, who invited him in 1968, when Gregory was running a long-shot presidential campaign on the Peace and Freedom ticket, and UT’s administration, who deemed him inappropriate. In April 1970, he finally appeared before a packed house at Alumni Memorial before 4,000 “wildly enthusiastic” attendees.

Several US Supreme Court justices have spoken on campus, beginning of course with Edward Terry Sanford, the UT alumnus who, before his death in 1930, spoke on the Hill hundreds of times. In more recent times, UT has welcomed Elena Kagan, Clarence Thomas, Antonin Scalia, and Sandra Day O’Connor.

Retired Chief Justice Warren Burger presided over several events on campus in 1993, partly in honor of his friend, Knoxville federal Judge Robert Taylor. He denounced grandstanding “Rambo lawyers” who he believed were dividing America by drawing dramatic attention to themselves.

It’s hard to imagine modern literature without the authors, poets, and playwrights who spoke at UT over the years. Modern poet Randall Jarrell spoke at the University Center in 1958.

Pearl Buck

Pearl S. Buck, whose novel about China, The Good Earth, was a major factor in her winning the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1938—the first American woman to do so—was 74 when she spoke at Alumni Memorial in 1967 about the problems and promise of contemporary Asia and to raise awareness for her foundation for the Asian children of American servicemen.

“Fugitive” poet Allan Tate spoke at the University Center in 1967. His sometime ally, Pulitzer-winning novelist Robert Penn Warren, spoke at Alumni Memorial the following year.

Novelist Saul Bellow attended a “Man and His Environment” event in April 1968. Known for his recent novel, Herzog, he was already honored, but greater fame came eight years later when he won both the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction (for Humboldt’s Gift) and the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Controversial modernist playwright Edward Albee gave a speech and a lively question-and-answer session at the Carousel Theatre in 1976.

British novelist Christopher Isherwood, here for the premiere of a dramatic interpretation of his novel, A Meeting by the River, spoke at Clarence Brown Theatre in early 1979. In 1980, playwright Tennessee Williams gave several talks at UT, his father’s alma mater.

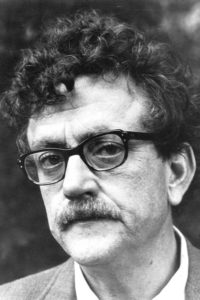

Kurt Vonnegut

Other literary speakers include John Gardner, Joseph Heller, Howard Nemerov, Marge Piercy, James Dickey, Lee Smith, Bobbie Ann Mason, and Norman Mailer (who had spoken at UT at least once before his final talk here in 1999). In 2001, Kurt Vonnegut returned to a campus where he briefly attended school in the early 1940s to give a talk to an overflow crowd at the University Center.

And, of course, Alex Haley, who spoke at the UC ballroom in 1983 just as he was moving to the area permanently. It was the first of many lectures at UT for Haley who would later become an adjunct faculty member in the College of Communication and Information. He’s one of a few UT visiting speakers whose connections to UT rise to significance in their own lives.

Elizabeth Gilbert actually completed her international bestseller Eat, Pray, Love, in 2005 while she was working at UT as a teacher of creative writing.

Poet Robert Lowell gave the final reading of his career in the UC’s Shiloh Room in May 1977. He seemed ill during his visit and died in New York four months later.

He’s not the only major lecturer whose appearance at UT turned out to be his last. Russian-born modernist architect Louis Kahn worked with students at Estabrook Hall but gave a public lecture at the downtown Hyatt in February 1974, inaugurating UT’s Bob Church Memorial Lecture series, named for the architecture dean who was one of Kahn’s students, which continues today. He died unexpectedly in New York the following month.

An even more famous architect had spoken at UT a few years earlier at a climax of his career. In April 1967, Buckminster Fuller spoke at Alumni Memorial. It was at the height of the global fascination with his geodesic dome that formed the US pavilion at the Montreal World’s Fair, set to open weeks later.

Most of these were famous before they spoke at UT. British journalist Alistair Cooke was no household name when he spoke at a UT student forum in 1962, almost a decade before beginning his long tenure as host of Masterpiece Theatre.

UT rarely entertained comedians before recent times, but a few humorists, including Art Linkletter (1965), publisher Bennett Cerf (1966), “Li’l Abner” cartoonist Al Kapp (1967), and columnist Art Buchwald, who spoke at UT several times, were here long enough to draw a few guffaws.

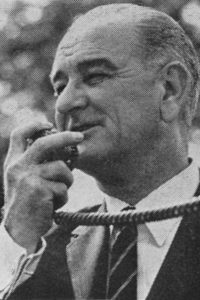

President Lyndon Johnson

In 1970, UT inaugurated a new holiday in an especially memorable way. For the very first Earth Day, the guest lecturer was Jane Jacobs, author of The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Although already well known then for her work opposing thoughtless development in New York, Jacobs would only later be acknowledged as the godmother of the international New Urbanist movement.

The first president to visit UT’s campus was probably Lyndon B. Johnson, whose motorcade paused in front of the University Center in 1964, when he was in town promoting his War on Poverty. Richard Nixon’s more famous, and more controversial, speech at Neyland Stadium followed six years later. Ronald Reagan discussed world trade at the UC in 1985 and President George H. W. Bush spoke about his administration’s educational goals in 1990.

President Richard Nixon

Heads of state visiting UT haven’t all been US presidents. In June 1976, General Jaafar Numeiri, president of Sudan, thanks to a military coup, was the honoree of a luncheon at the University Center. Accompanied by 40 Sudanese officials, he emphasized the kinship between Tennessee and Sudan. Soon after, though, he became an Islamist, instituting Sharia law. He was ousted from power in 1985.

And a few royals and nobles have made their way to campus. Prince Albert of Liege, many years later known as King Albert II of Belgium, took a quick tour of campus in 1955 as local reporters seemed mainly concerned in whether he was dating a UT coed he danced with at Cherokee Country Club.

There have been, of course, hundreds more. Timothy Leary, Bob Woodward, G. Gordon Liddy, Ted Turner, Tom Brokaw, lunar astronaut Harrison Schmitt, Henry Kissinger, David Halberstam, Sue Grafton, Al Gore, Edwin Newman, and Bill Nye the Science Guy. You may have your own list of major characters on the global stage you saw at UT, or wish you’d seen. The world would be unrecognizable without the hundreds of thinkers who at least once made it a priority to come speak at UT’s campus.

It’s never too late to catch the next one.

This story is part of the University of Tennessee’s 225th anniversary celebration. Volunteers light the way for others across Tennessee and throughout the world.

This story is part of the University of Tennessee’s 225th anniversary celebration. Volunteers light the way for others across Tennessee and throughout the world.

Learn more about UT’s 225th anniversary