In the not too distant past, an honors research project usually comprised a thesis, 60 or so pages of supporting arguments, a smattering of primary and secondary sources, and a nice plastic slipcover.

Today, library trips and a carafe’s worth of ink are still essential to many honors projects, but a growing number of students are forsaking the study carrel for the film studio, the conservatory, or the forest. In the case of honors students Jenny Bledsoe, Jaclyn Barnhart, and Jayanni Webster, such projects involved journeying abroad and into research work that was anything but traditional. Here, these three remarkable students share their experiences abroad and what they learned on their nontraditional journeys.

Renaissance Woman

Jenny Bledsoe is a few centuries ahead of her time. Although her studies focus on the late medieval period, Bledsoe is a textbook example of a Renaissance woman. This year alone, the religious studies major is completing her Chancellor’s Honors Program honors thesis project, editing the University of Tennessee’s undergraduate research journal, Pursuit, serving as a teaching fellow for a first-year seminar class, chairing the steering committee of the Honors Symposium, and participating in the Honors Ambassadors Program, in which honors students speak to prospective students and parents about academics and life at the university. The only thing that might be missing is a Lady Vols jersey.

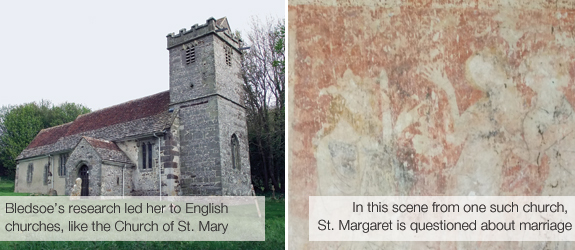

First and foremost on Bledsoe’s plate is her research project, which thus far has involved a substantial use of interlibrary loan services, some intercontinental travel, and even a dragon. Her paper explores depictions of the fourth-century virgin martyr St. Margaret of Antioch and how her story was used to shape collective and individual devotional practice in the Middle Ages.

“I’m mainly working with saints’ lives, and particularly with virgin martyr legends,” she says. “I’m really interested in the texts and what the authors’ intentions were for the texts, and how the readers might have used them in their own lives.”

Bledsoe’s research project developed from a fall 2009 graduate- level class she took with Mary Dzon, an assistant professor in the English department. Under the guidance of English professor Thomas Heffernan and religious studies associate professor Christine Shepardson, Bledsoe developed her thesis and selected sources to study. By spring 2010, she was planning a research trip to Europe.

“I stumbled across this church in England that has 14 scenes from Margaret’s life, and the paintings are all from the 14th century, and they’re of remarkably good quality,” she says. One of the more stunning paintings shows Margaret bursting from the stomach of a dragon, which had eaten her but then exploded when she made the sign of the cross in its stomach.

In summer 2010, Bledsoe visited this church, as well as others across Europe. Her travel was funded in part by grants from the Office of Research and the Chancellor’s Honors Program.

Bledsoe and other undergraduates from across the country will present their research at UT this spring during a conference Bledsoe herself organized, which will present research on the subjects of mysticism, heresy, and witchcraft in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance.

In addition to the conference, Bledsoe is also chairing the steering committee for this year’s Honors Symposium, a daylong event during which students in campuswide and/ or departmental honors programs present their original research to the university community and the public. Participating students gain valuable experience presenting research information to others—a task that will help them in their future careers, as well as graduate school, should they choose to go.

Her research project may be the most involved of Bledsoe’s honors projects, but it is by no means her only endeavor. She also serves as editor-in-chief of Pursuit, the university’s undergraduate research journal, and she participated in UT’s honors teaching fellowship program, in which upper-class honors students help teach a first-year honors seminar. Fellows help freshmen get engaged on campus, providing answers and advice to students adjusting to college-level academics and their new social lives.

“It’s a problem with freshmen just feeling overwhelmed and not knowing how to get involved,” Bledsoe explains.

Her teaching, leadership, writing, and myriad other skills will no doubt pay off when Bledsoe applies to graduate school, which she is currently doing. She hopes to specialize in late medieval religious culture.

—Meredith McGroarty

Reciprocity in Rwanda

“Mandatory volunteer work” may sound like an oxymoron, but for several years the government of Rwanda has been implementing just that, hoping that state-mandated public service can help heal a society fragmented by past violence.

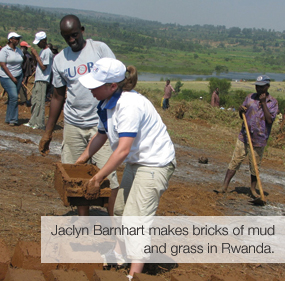

Jaclyn Barnhart recently traveled to Rwanda for an internship; while there, she also studied the country’s system of governmentorganized public service work, called umuganda. Her research, which she presented last spring at the Honors Symposium, grew out of her desire to learn more about the social and political possibilities and realities of such a system.

Umuganda was part of Rwandan society before the country’s mass killings in 1994, but during the genocide it became a tool for leaders to mobilize masses of people and have them conduct activities such as burning houses, enforcing roadblocks, and committing murder. Since the genocide, however, the Rwandan government has worked to restore umuganda to its original purpose: the performance of work for a collective good. The practice also aims to effect reconciliation and build a positive, singular national identity among Rwandans.

Now, umuganda takes place from 7 a.m. until noon on the last Saturday of every month. During that time, all Rwandan citizens perform various public service activities, such as public property maintenance, street cleaning, and construction. After the work, a local official gives a lecture on a selected theme.

Barnhart’s umuganda service included several manual tasks, including making bricks composed of mud and grass. At the end of the day, Barnhart and a fellow UOB employee had together made a total of 24 bricks. This firsthand experience lent depth and a necessary perspective to Barnhart’s research.

In addition to simply participating in umuganda, Barnhart examined how the practice relates to political mobilization and the construction of individual and national identities. She considers the current umuganda project to be largely unsuccessful, both in its ability to achieve unified political mobilization and in its goal of cultivating a singular national identity.

“Rwandans seem to identify with their Hutu or Tutsi status before their Rwandan identity,” she says. However, Barnhart feels some of this project’s findings may also be beneficial to the United States and its citizens.

“We must appreciate our interconnectedness and, therefore, our roles as stakeholders in the lives of everyone,” she says. “America could learn a lesson from this: avoid conflict by emphasizing the ‘American’ values of equality and of celebrating diversity.”

Barnhart is a senior in global studies. After graduation she plans to serve in Teach for America and the Peace Corps. She hopes to work in a field that promotes social justice and empowerment, which she feels will be found with a small nongovernmental organization that focuses on literacy and community organization, either in the United States or Latin America.

—Ariel Cowen (’10)

Teaching Peace in Uganda

Jayanni Webster’s experience as a student in the Memphis city public school system sparked her interest in education and society, particularly education policy and school-based programs focusing on issues like violence prevention, leadership, and cultural education.

“I always think of education as the fundamental basis of all human rights. If you educate a person on these issues, then they can be an upstanding citizen for those specific rights in their everyday lives,” she says.

Webster says she became interested in African education when she came to UT and got involved in the Jazz for Justice Project, an organization started by religious studies professor Rosalind Hackett in 2006 to raise awareness of the challenges facing northern Uganda. The group raises funds for peacebuilding and arts-related efforts in northern Uganda through creative endeavors like jazz concert benefits and sales of T-shirts and Ugandan-made jewelry and bags. The informal relationships forged by Jazz for Justice and Hackett with the communities in northern Uganda will soon be cemented when UT launches its new Gulu Study and Service Abroad Program, in which UT students will travel to the region to study and engage in service-learning projects (see sidebar).

“My work with Jazz for Justice inspired me academically. I became so passionate about Uganda, and I wondered how I could apply it to my schoolwork,” Webster says.

She decided to participate in the College Scholars program, which gives students more flexibility in their studies, including the ability to develop their own major. Webster is working toward a specialization in post-conflict education in Africa.

For her research project, Webster chose to combine her interest in education with her involvement in Ugandan issues by investigating several peace education and positive reinforcement children’s programs in northern Uganda. She says this idea sparked another research project when she saw how Facing History in Ourselves, a social responsibility-promoting program she participated in during high school, shared many messages and components with one of the peace education pilot projects in Uganda.

“I thought that was amazing, just how far that program had traveled and how it was revamped to fit the cultural things going on in northern Uganda, like putting in a component of conflict resolution,” she says.

During the spring and summer of 2010, Webster was able to conduct research in northern Uganda, designing her own itinerary. She interviewed teachers and students about their experiences with a peace education program administered by USAID and one run by a Boston-based nonprofit organization called Inside Collaborative; performed internships with groups like the Acholi Education Initiative and the Pincer International Limited Group; and examined the differences between community- based groups and foreign or national organizations.

The second part of Webster’s research will take place closer to home, examining how societies in the United States deal with youth education on issues of nonviolence, peace, leadership, cross-cultural understanding, and character development. She will be working with groups in the Knoxville community, such as the Boys and Girls Clubs. Her research here was recently given a boost by UT’s Howard H. Baker Center for Public Policy, which awarded Webster a spot as a Baker Scholar for the 2010-2011 academic year.

Thinking further ahead, Webster hopes to return to Africa to study. She plans to pursue a Fulbright Fellowship or work for a refugee resettlement agency in the United States before applying to graduate school for a master’s degree in peace and conflict studies or international human rights law.

1 comment

I am fascinated by Jenny Bledsoe’s research. Has she published anything yet? I would love to read more, as both a scholar in religious and gender studies.

Comments are closed.