The Saturday evening before the University of Tennessee GE College Bowl team was to take on Manhattan College, they went to Broadway’s Majestic Theatre and saw Camelot with William Squire as Arthur and Patricia Breden as Guenevere. On a page of her Playbill, the team’s coach, physics professor Isabel Tipton, scribbled in pencil the opening lyrics of a Guenevere and Arthur duet and key words of its four verses: “What do simple folk do—when they’re blue? Whistle, sing, dance, wonder what Royal folk do?!”

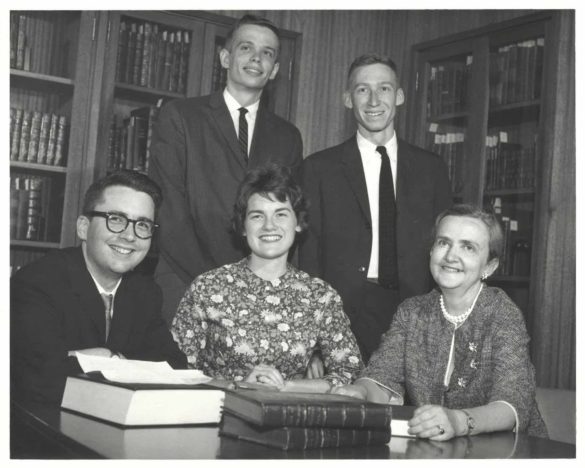

CBS program from the 1962 GE College Bowl.

It might have occurred to Tipton at the start of the experience that her team of Anne Dempster (now Anne Dempster Taylor), Joseph Gorman, David Rubin, and Harold Wimberly Jr.—whom she and eight alternates had drilled for two months—might have been seen as simple folk from East Tennessee. But after their upset of Manhattan College and three succeeding weeks of victories, they impressed a nationwide TV audience with their strong intellectual performance, earned a tickertape parade down Gay Street and Cumberland Avenue, and inspired 114 UT fans in three hired buses to journey to New York City to view their fifth and final match against the University of Rochester.

Wimberly recalled in later years, “We got a bigger response nationally than any other school, because no one expected that a team from UT could win. We were looked upon as a backwoods school. At that time, UT didn’t even have a Phi Beta Kappa chapter.” Three years later, a chapter of the prestigious academic society was established at UT, influenced in part by the team’s accomplishments. (Two of the team members, Gorman and Rubin, were inducted retroactively.)

Twelve Gaping Mouths to Feed

In late February 1962, the GE College Bowl informed UT officials that their team would appear on the program on May 6. “Dr. Isabel H. Tipton, professor of physics, guessing only in part what she was letting herself in for, agreed to coach the team,” wrote James F. Davidson, assistant dean of the College of Liberal Arts and a professor of political science, in the Tennessee Alumnus magazine.

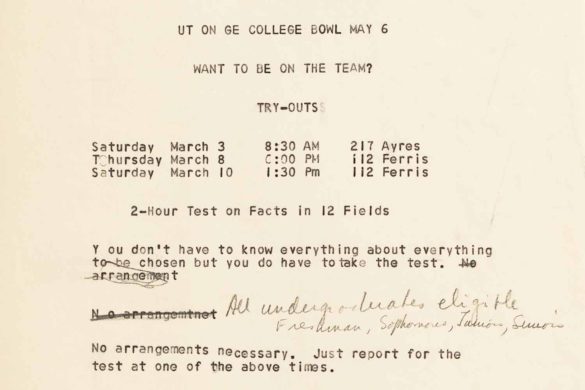

All undergraduates were invited to try out for the team. “The program does not pretend to be a balanced test of scholastic ability,” the announcement read. “It is frankly intellectual gamesmanship, stressing quickness of response and a wide range of information. As in all games, luck plays some part. Yet to thousands of viewers each Sunday these teams represent the students and the instruction at their respective schools. The University of Tennessee is committed to producing a team of ‘varsity scholars’ who can meet the best that X University has to offer.”

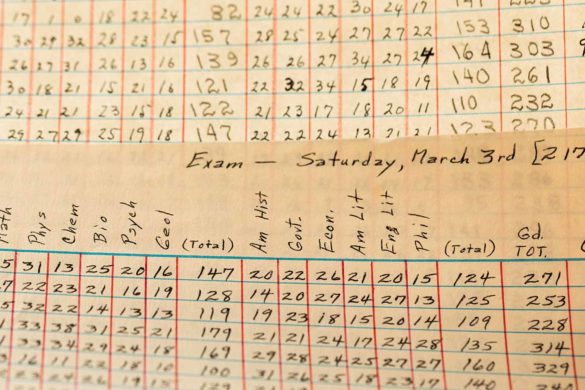

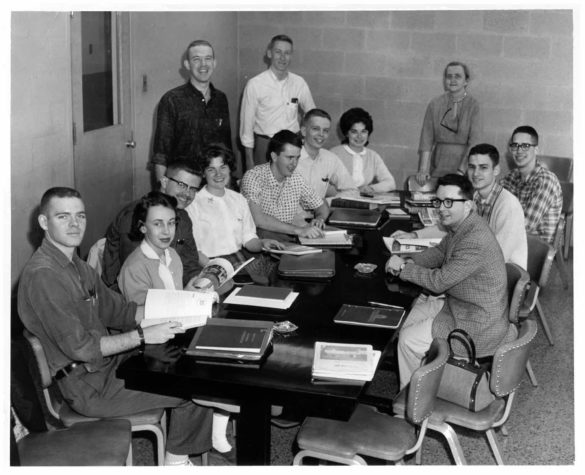

Of 182 students who took the written test, Tipton, assisted by other faculty members, tested 69 verbally and selected 12. Divided into three working teams, they formed the basic group that produced UT’s winning team. Every afternoon in April, eight or more of them met with Tipton in a room in the University Center for practice contests and review sessions. They did research on their own and brought information to the group. They quizzed one another privately. They consumed a thousand questions a week. Rubin remembers, “She was a wonderful teacher and extremely well organized.”

“Dr. Tipton stated immediately that this was going to be coaching and training and work to get there, which we did,” Dempster Taylor recently said. “So we played competitive games every day after class. We even made up a lot of questions and tested each other with questions. And we learned how to do the buzzer so that we weren’t going to be locked out. You know, the first person on the buzzer locks out everyone else. So you learn to be very fast.”

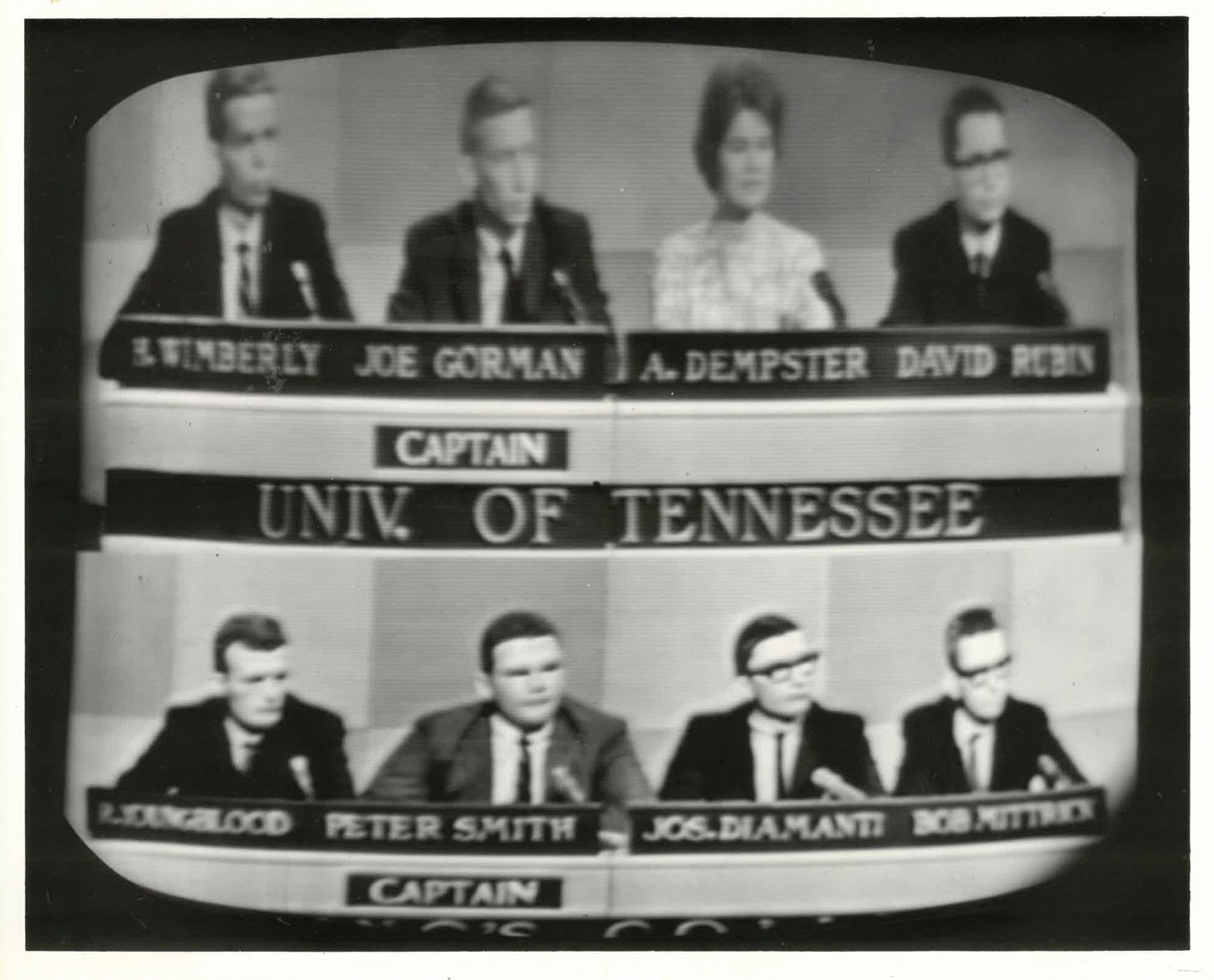

While the other eight members continued to provide questions and competition for practice, the team’s four principal members were designated in the last week of April:

- Team captain Gorman, a senior history major from Central High School in Knoxville, was attending UT on a full academic scholarship and had a 3.45 GPA. “A straight arrow,” remembers Rubin. Gorman was strong in history, geography, politics, and current events.

- Dempster, a sophomore fine arts major from West High School and St. Catherine’s School in Richmond, Virginia, with a 3.85 GPA, was only 18, having skipped a grade in her early school years. Besides knowing history, art, and literature, she did well on sports questions.

- Rubin, a senior French and English major with work in classics from Oak Ridge High School, had gone to the University of Chicago for his first year of college and had poems published in Poetry, the Quarterly Review of Literature, and the Chicago Review. He had a Barton Scholarship at UT and had been offered Woodrow Wilson and Fulbright Scholarships to graduate school. He was a solid scorer because of his wide knowledge of literature, mythology, and geography.

- Wimberly, a sophomore physics major from West High School in Knoxville, had won a National Merit Scholarship to UT and carried a 3.94 GPA. He was quick on the buzzer to answer math and science questions and demonstrated knowledge in all fields.

The team’s Friday practice games were open to the public. WBIR televised two practice broadcasts, aired at 4:30 p.m. on Friday afternoons, pitting the three UT units—Blue, Red, and White—against one another. DeWolfe Miller, an English professor, served as quizmaster. “It was good to see him again,” remembers Rubin. “I had done a reading course with him in American literature my sophomore year. He was a former FBI agent, so he knew how to aim questions at you.” The performances were valuable preparation, and the UT first team noted later that it was harder to beat their own second team than some of the college teams they faced.

Reader toss-up question No. 1:

In addition to serving as mayor and city manager of Knoxville, George Dempster (Anne’s great-uncle, credited with inventing the Dempster-Dumpster) served on the commission to create the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Which former UT quarterback, who also served on that commission, is known as the Father of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park? Toss-up answers are given at the end of the story.

New York, New York, What a Wonderful Town

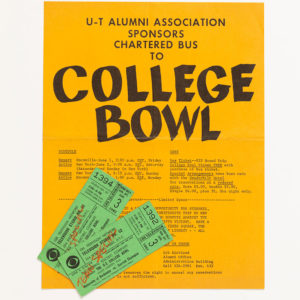

Souvenirs of the UT team’s trip to New York City to appear in the 1962 GE College Bowl.

The first match was scheduled for Sunday, May 6, against Manhattan College, which had won three matches. On Friday, May 4, UT President Andrew Holt spoke at a rally sponsored by the Student Government Association before joining the 12 team members for their noon flight to Liberty Airport in Newark, New Jersey. The team was met in Newark by Tipton’s daughter, Jennifer, who was then beginning her career designing lighting for Broadway shows. She enjoyed the time with her mother on the limo ride to the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel on Park Avenue.

The team saw Camelot on Friday evening. They toured the United Nations building on Saturday afternoon and were feted as guests of honor at the New York Area UT Alumni Association annual reunion banquet, along with Vice President for Development Edward Boling and Knoxville attorney Foster Arnett, who was then president of the Greater Alumni Association.

“I was just thrilled to be there,” Dempster Taylor remembers. “It was the first time I was able to see art in the Museum of Modern Art instead of Dale Cleaver’s slides in art history class. Everything about the city was exciting. We heard Gene Krupa play at the Village Vanguard. We even went to an Automat-type restaurant in Times Square. That first weekend, all 12 team members made the trip, because we didn’t know if there would be a second one.” On each of the following weekends, one alternate came along.

More souvenirs.

In CBS-TV’s Studio 52 at 254 West 54th Street, the quizmaster was Allen Ludden, longtime emcee of the game show Password and soon-to-be third husband of Betty White. The Sunday schedules were demanding. “We had to arrive at the theater by 8:30,” Rubin remembers. After makeup and other preparation, the day’s timeline was tight:

- 11 a.m.–noon, briefing with Mr. Ludden

- 12:15–1:15 p.m., lunch with producer Mr. Cleary

- 1:30–2:55 p.m., rehearsal with buzzers and practice questions

- 2:15 p.m., view campus film

- 2:30–3:30 p.m., rehearsal with camera and practice questions

- 3:30–4:30 p.m., break

- 4:30–5:30 p.m., dress rehearsal

- 5–5:30 p.m., break

- 5:30–6 p.m., on air

“When Allen Ludden began the questions in the morning briefing and each question was met with four simultaneous raps from our side of the table,” Tipton told a reporter, “Manhattan knew they had met a team.” Rubin was impressed by the mountainous sandwiches from the iconic Stage Deli on Broadway. Dempster narrated the film about UT’s campus that was shown during the broadcast.

The UT team during a broadcast.

For the first on-air question, Ludden rolled a ball down a plank and asked, “Who discovered the—,” but he was interrupted by Wimberly’s buzzer as he shouted, “Galileo!” In the first toss-up question, Wimberly gave the first line of Richard Lovelace’s poem “Iron Bars Do Not a Prison Make.” He went on to answer toss-up questions concerning Alaska, Einstein’s theory of relativity, and Oliver Twist. Dempster answered questions about a painting of Charles I and the location of the Rhine River. In other toss-up questions, Rubin identified Talleyrand’s description of coffee and works by Goethe.

Holt was described as “cheering lustily in the audience.” UT’s victory was decisive and, to some, surprising. The team returned to a reception at Knoxville’s Municipal Airport, with a red carpet provided by the Knoxville Chamber of Commerce and a turnout of faculty, students, and university officials.

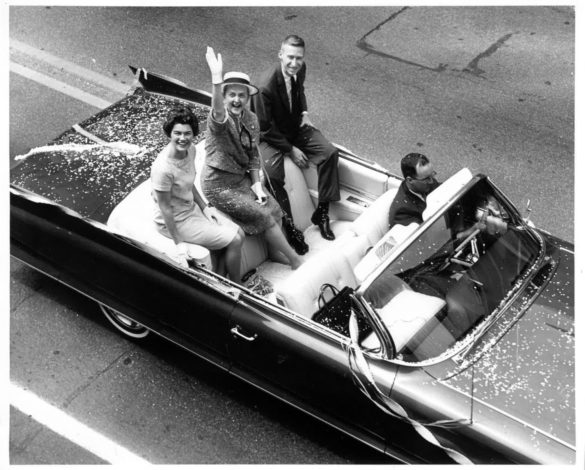

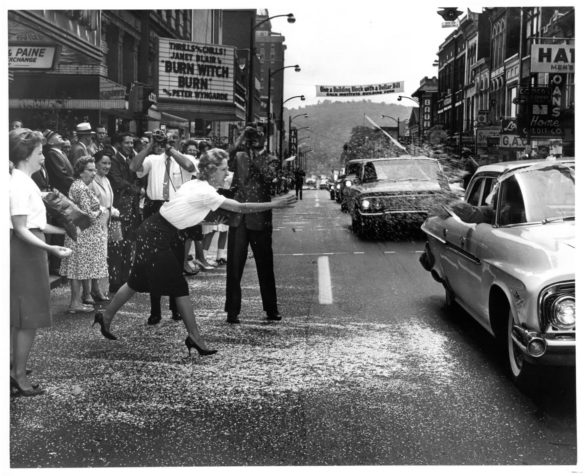

Photos of the team’s return to Knoxville.

The team’s next opponent was King’s College of Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania. Beforehand the team saw A Thousand Clowns with Jason Robards Jr. and Sandy Dennis, but Rubin was not with them. He was dating a girl he had known at Chicago, Nina Erlich, whose family lived in the leafy Riverdale section of the Bronx. “She had made her mind up that I was a hick from the sticks, and I needed to be acculturated,” Rubin recalls. “She had seen all the shows that the rest of the team signed up to see, so we saw things like The Prodigal Son at the New York Ballet.”

“In the second game, Harold and I figured out the strategy to demoralize the opposing team,” Rubin recalls. “We’d get into conversations that covered the same subjects as the questions. We made them think that they didn’t know what they were talking about. They’d say something, and we’d say, ‘Well, you know that’s not true.’ Harold was poker faced, and we gaslighted them. We reduced one or two people to absolute silence on the air. They absolutely lost their confidence. Dr. Tipton never knew about it. Neither did Joe or Anne.”

The Knoxville Journal ran a full-page banner headline, “UT ‘Brain Bowl’ Team Wins Round Two.” (The headline below, in much smaller type, read “US Pacific Forces Alerted As Reds Sweep Over Laos.”) At the airport on their return, Rubin’s mother, Jeanne, who had gotten calls from relatives all over the country, was overheard to say that the publicity was getting out of hand: “Last night we were introduced as David Rubin’s mother and father.” His father, Ira, was an analytical chemist in the biology division of Oak Ridge National Laboratory.

The Knoxville newspapers covered the College Bowl team with the fervor usually reserved for football. Mary Anne Winegar of the Knoxville News-Sentinel even reported on a jinx. This was the Tennessee jinx—Tennessee Williams, that is. The first two teams UT upset had seen Shelley Winters in Williams’s The Night of the Iguana before their Sunday showdowns. Refusing to be superstitious, Tipton and her husband, Sam, saw Iguana the evening before the Rhode Island match. But her team went to How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying.

Reader’s toss-up question No. 2:

Playwright Tennessee Williams had many family connections to Knoxville, including an ancestor, Colonel John Williams, a US senator and diplomat who may have originated the name Tennessee Volunteers thanks to his battles with Native American tribes during the War of 1812 era. Late in life, he lived in a house on Riverside Drive. Tennessee’s father, Cornelius, grew up in Knoxville, went to UT, and is buried in Old Gray Cemetery. In which of Williams’s plays is there a mental institution with the Knoxvillian name “Lion’s View”?

“Give ’em Hell with Isabel!”

The third-week opponent was the University of Rhode Island. UT’s Dean of Students Ralph Dunford and Liberal Arts Dean Kenneth Knickerbocker, a former URI faculty member, made the trip. Gorman led off the game by answering correctly that Herbert Hoover had run for and won the presidency after Calvin Coolidge decided not to run.

On Wednesday, May 23, Senator Estes Kefauver (’24) sent congratulatory letters typed on US Senate stationery to Dempster and her parents. His handwritten note to George Dempster ended, “How very proud we are of your niece. Just like her uncle, a great TV personality.”

Reader toss-up question No. 3:

US Senator Estes Kefauver (D.-Tenn.) was famous for wearing a coonskin cap on the campaign trail and chairing hearings on Mafia crime families in the early 1950s. In which Oscar-winning movie are Kefauver and these hearings depicted?

Tipton’s son Joe (’69, ’71), then a sophomore at Webb School of Knoxville, recalls hearing chants of “Give ’em hell with Isabel!” Dempster’s brother John (’72, ’77) was a sophomore at McCallie School in Chattanooga. “We would watch on TV in the dorm common room then rush to Sunday night chapel, which started at six,” he said recently. “Lots of guys were cheering for the team. Even the headmaster stopped me one day and asked if Anne was my sister. He then praised UT as a fine university, as I recall. I think he also hinted that I should apply myself more in my classes—an ongoing discussion!”

The TV audience had gotten to know the contestants. “At one point,” remembers Rubin, “Nina and I had taken a cab, and the taxi driver turned around and looked at us and said, “Aren’t you the little guy who sits at the end of the table?”

The fourth round was against St. Olaf College of Northfield, Minnesota. UT won, but the TV audience didn’t get to see it. CBS pre-empted the show to air an interview with astronaut Scott Carpenter, angering local viewers. A story in the News Sentinel the following day said, “Knoxville television viewers nearly went wild at 5:30 p.m. yesterday. Some even stormed WBIR-TV’s Hutchinson Avenue offices, pounding on doors trying to get in.” Rubin’s mother said that friends called her asking why the show wasn’t on. She said one of the calls was long distance, and before she was connected “the operator wanted to know if we had won.”

Reader toss-up question No. 4:

Why did Heidi become synonymous with networks’ longstanding policy of sticking with football games until the end and pushing back scheduled shows?

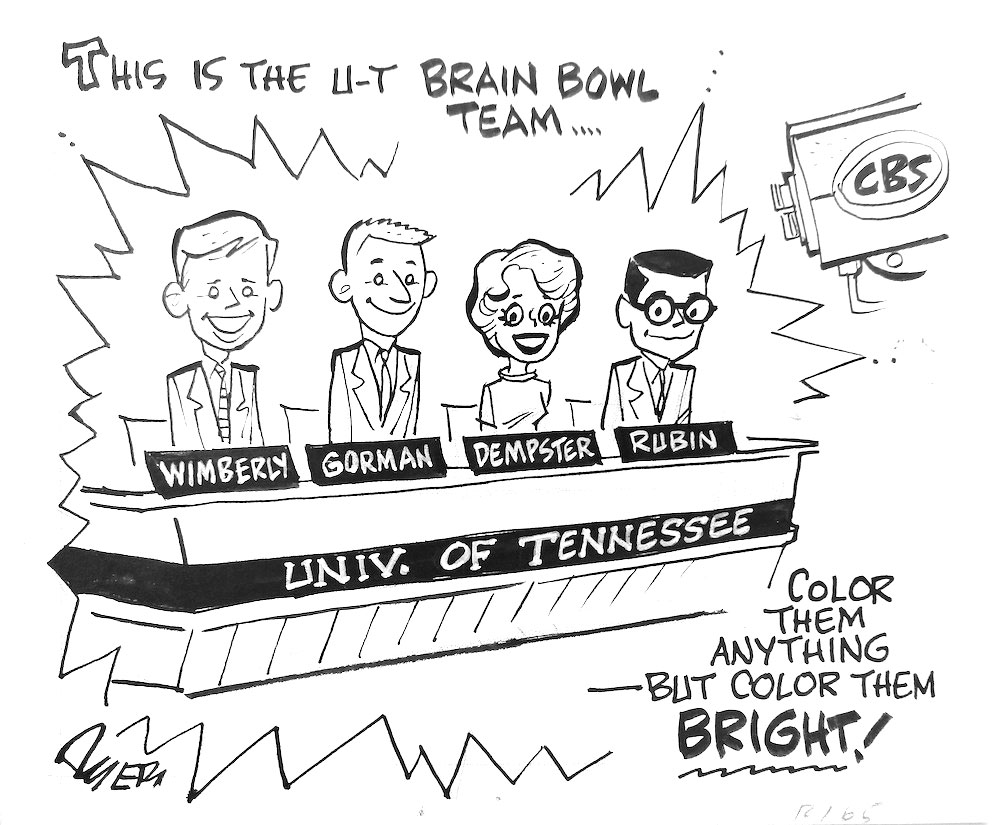

A commemorative drawing presented to the contestants by Knoxville News-Sentinel cartoonist Bill Dyer.

That week Winegar profiled the team in the News-Sentinel. Here are excerpts:

“Anne,” Dr. Tipton says, “is the belle of the network. Everybody in the whole program loves her. The cameramen keep the camera focused on her whenever they can.” . . . Like her teammates, Anne has always been a good student. She likes to learn and has read a great deal. She had impressed many by answering a question about home run hitter Roger Maris and the figure formed by the stitches on a baseball.

When Joe Gorman became a College Bowl team member, he was planning to study law. That’s changed because of College Bowl. Delving into one subject after another to study for the show made him realize how much he enjoys learning. Now he plans to go into college teaching. He was met at the airport after the third game by a representative of the U-T history department, offering a $1,000 assistantship for next year. He has accepted it.

“The nice thing about Joe,” said Tipton, “is the real kick he gets out of the work he has to put into preparing for the shows.” . . . On the television show, he’s sure and steady. “You always feel comfortable when questions on American history, maps, and such come up,” Dr. Tipton said. “You know he will get them.”

Harold Wimberly is a quiet, studious young man. . . . Television audiences know Harold as the force team member who bolsters his team by answering questions quickly—often before Mr. Ludden has completed the question.

Dr. Tipton calls this Harold’s “competitive spirit.” “Mr. Ludden says this is what it takes to win games. Students must know the information, but they must have the competitive spirit. Harold has kept the whole team fired up with it. Being on the College Bowl team has influenced all the team members, but the influence is perhaps most apparent in Harold. “He has grown up and blossomed out. For example, he has always had a delightful sense of humor, but his quiet nature sometimes hides it. His television image is so attractive. The College Bowl producers received a letter from a Tennessean saying that when U-T’s stay on the show was over, he wanted to run Harold for governor. . . . He also comes up with amazing things,” Dr. Tipton said. “He knows literature, history and geography.”

Harold doesn’t let mistakes bother him. He flubbed a question and helped St. Olaf. . . . Both teams were asked to identify a chemical formula . . . he answered “Sugar and molasses.” St. Olaf picked it up and answered correctly, “Sulphur and molasses.” “Because Harold is young,” said Tipton, “it would be natural for him to get rattled after doing that. But he didn’t. I was so proud of him for not getting rattled.”

Friends in Knoxville—and new ones in New York—have started calling Harold and David Rubin “Mutt and Jeff.” Harold is 6 feet, 2 inches tall, and David is exactly one foot shorter.

David, the only non-Knoxvillian on the team, is a friendly, brilliant, and very witty Oak Ridger. . . . Dr. Tipton breathes a sigh of pleasure when she speaks of David. “He is the strength, depth and length of the team. His knowledge is so sure and so deep—and he is so sweet with it all. He has such a marvelous disposition.” . . . David’s confidence in himself shows through on the television program and bolsters the confidence of his teammates and of his viewing audience. “When David starts to answer a question,” Dr. Tipton said, “you just know everything will come out all right.” David is considered the team’s anchor man because of his wide knowledge of literature, a field in which many questions are asked each week.

The Final Showdown with Rochester

Flyer and tickets from the chartered bus taking fans to New York to see the team in action against Rochester.

The week before their final match against the University of Rochester, the UT team had final exams, which may have taken a toll. “We were all very tired and the show was very high stress,” remembers Rubin. Earlier in the week Tipton had confessed to Powell Lindsay of the News-Sentinel that she was worried. “They’ve let down,” she said despairingly. “I don’t think they are overconfident, but all this hullabaloo—I’m afraid they may forget what they’re going to New York for. Mind you, I think we can take Rochester. But we’re going to have to buckle down to do it.”

Inspired by the $6,000 that the team had already won for the UT scholarship fund, leaders in Knoxville began a drive for a matching Bowl Fund. Mayor John Duncan contributed $100. Dempster Brothers added $500. The Optimists Club and City Salesmen’s Club Vice President W. Dwight Kessell encouraged firms to match the funds won by the team. Within a couple of weeks, the effort had raised $7,450.

On June 1, the team was sent off to the airport with a tickertape parade down Gay Street and Cumberland Avenue. Some 114 supporters paid a round-trip fare of $25 to pile into three buses chartered by Alumni Association Secretary John Smartt, whose brother-in-law, English Professor John C. Hodges, was then wrapping up the fifth edition of his Hodges’ Harbrace College Handbook.

Reader toss-up question No. 5:

In its many editions since it was first published in 1941, the Hodges’ Harbrace College Handbook has become the largest-selling college textbook of all time, and its royalties helped to build UT’s Hodges Library. What number is the current edition?

Smartt also arranged for the Vanderbilt Hotel to offer the Vol faithful reduced rates of $5.50 per person, double occupancy. Many were seeing New York for the first time. Lindsay quoted an enthusiastic student as saying, “I’m just gonna walk all over that town,” as the buses sped through Virginia.

On Saturday, June 2, the team, minus Rubin, had a light lunch at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. That night they saw Zero Mostel in A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum.

Rubin’s degree was scheduled to be conferred at commencement on the morning of Sunday, June 3, which would have made him ineligible for the competition. “They concocted a scheme to delay the presentation of my degree,” Rubin remembers. “So with five minutes to go in the broadcast, Allen Ludden handed me my diploma.”

“The game was a close, see-saw one,” wrote Lindsay in the News-Sentinel. “Neither team seemed to be at their peak. A more-than-usual amount of questions were answered incorrectly—or went unanswered by both teams. Neither team was able to answer the first question, which dealt with Mercator projection maps (which exaggerate the size of countries). Rochester incorrectly answered the second toss-up and was penalized five points. U-T’s David Rubin answered correctly—identifying A. Conan Doyle as the writer whose works are translated into 40 languages, and U-T led 25 to minus 5.

“By halftime Rochester led 110–90. The lead changed hands four times. Rochester won two music toss-ups, and U-T failed to identify three famous waltzes, one from Die Fledermaus, one from Romeo and Juliet, and one from Masquerade Suite. Gorman missed a question about the geographical relationship between Laos and Thailand.

“At the show’s end, the U-T team looked downcast, and Anne Dempster turned her head and fought back tears.”

“Oh, my goodness,” says Dempster Taylor today. “I don’t recall that. But I possibly did.”

“Well, we feel what we felt at the time—that we came very close, and that’s a good feeling, you know, when you put out as much as you can,” she recalls. “And we were winning on the practice matches all day long. We rehearsed retiring the trophy. And then suddenly that last match didn’t go our way. And so we didn’t finish the way we wanted to, but that’s being on a team. That’s what you do when you compete.”

“We got the wrong questions,” Tipton told Lindsay after the final. “The time was bound to come. The only way we could’ve won would have been for Rochester not to know them either, but they did. We just didn’t know those questions. UT lost 265–205 and missed out on being the eighth GE College Bowl team to go all the way to the championship, but they had the distinction of being one of only four out of 140 teams up to that time to have been four-time winners.

Reader toss-up question No. 6:

In 1977, CBS-TV’s Studio 52 at 254 West 54th Street was sold and became what famous nightclub, emblematic of the excesses of the 1980s and visited by countless celebrities?

Bonus Round

After graduation Gorman was working on his master’s in history when he met Bette Stubbs (’63), a history and Spanish major from Oak Ridge, in an education class. “Joe was heading to DC to do research on Estes Kefauver for his master’s thesis about the 1952 political campaign,” Stubbs remembered in a 2017 interview. “He realized that he would have to be a teacher to make ends meet, so he took the education class to get his teaching certificate.”

After Stubbs graduated in December 1963, they were married on December 27. Gorman received his PhD in history from Harvard in 1971. His doctoral dissertation, a political biography of Kefauver, was published in 1971 by the Oxford University Press. He went on to become a Library of Congress specialist in congressional research and an authority on political parties and presidential elections. He died on November 30, 1985, of cancer, at age 45. In 2017, Bette established a Department of History graduate travel fund endowment in Gorman’s name to support graduate students in their travel and research. “UT was very good to both of us,” she said after she created the endowment. “It was a great learning experience both socially and intellectually. We had great teachers and good activities. And travel was very important to Joe as a way of learning about the wider world outside of East Tennessee.”

Dempster became president of Chi Omega sorority and a Torchbearer. Robert L. Taylor Jr. (’64, ‘71), a UT master’s student in history, had seen her on the GE College Bowl and a mutual friend introduced them. They were married on March 14, 1964, and she graduated with her BFA on June 7 as Anne Dempster Taylor. She worked as a docent at the Baltimore Museum of Art and on the staff of Knoxville’s Dulin Gallery of Art, the precursor of the Knoxville Museum of Art. The couple moved to Murfreesboro, Tennessee, in 1969, where he taught history at Middle Tennessee State University. “When we came to Middle Tennessee,” she says, “I had been listening to people talk about history for several years, and it became a more and more interesting subject.” She got her MA in history in 1973 at MTSU and worked at the Webb School in Bell Buckle, Tennessee. “I think you’re seeing a pattern here,” she adds. “I’ve always really enjoyed learning new things, new subjects. I went to Vanderbilt and got an MBA in 1984, and that led me to some interviews, some opportunities that again, I didn’t quite know existed before I was exposed to them. And I worked in commercial real estate at Centennial Inc., in Nashville for close to 20 years.” Their daughter Eleanor and her family live in New York.

Rubin studied French literature for a year at the University of Paris on a Fulbright Scholarship. Sailing aboard the ocean liner SS France, his dining table of male Fulbright scholars swapped three seats with a table of junior-year-abroad college women. One was Carolyn Dettman, a Syracuse University student from LaGrange, Illinois, headed for a year in Grenoble, France. “In Paris, before she went to Grenoble,” recalls Rubin, “Carolyn organized a trip to the Folies Bergère. She was surprised at the nudity. We played gin rummy for hours across the street from her dorm at the Cité Internationale Universitaire de Paris. I don’t think I saw her again that year.”

The next fall he was on his way to start his master’s in French on a Woodrow Wilson Fellowship at the University of Illinois. Switching trains in Chicago, Dettman saw him on the platform and asked, “Aren’t you the boy from the boat?” A romance began. He got his master’s in 1964 and a PhD in 1966 from Illinois. After two years teaching at the University of Chicago, he was recruited by the University of Virginia, where he taught for 40 years. He and his wife have a grown son, Timothy.

Wimberly went to law school at UT and served as a general session judge for 13 years and circuit court judge for more than 25 years. He was a world traveler, an excellent photographer, a musician playing the organ and piano, and devoted Elvis fan, who kept images of the King in his chambers on the main level of the City–County Building. He died on January 24, 2020, after a brief illness. He is survived by his wife, Sarah, and son, Harold Christopher.

The College Bowl producers so respected the way Tipton had prepared her team that they asked her to help provide them with questions and answers, which she did for years thereafter. She won the UT Alumni Association’s Outstanding Teacher Award in 1966. When she retired in 1972, she had published more than 35 articles in peer-reviewed journals that have received more than 2,500 citations up to the present day. She died in 1980. A room in the Nielsen Physics Building is named in her honor, as is a graduate study room in the John C. Hodges Library.

In 2015, her daughter, Jennifer, one of Broadway’s most celebrated lighting designers and a longtime adjunct professor at the Yale School of Drama, endowed the Isabel H. Tipton Physics Scholarship, primarily for women. Her most recent trip to Knoxville was to design the lighting for the Clarence Brown Theatre and Knoxville Symphony’s 2018 joint production of Candide. Tipton’s three sons are Sammy Tipton, a retired physician; Hiram Tipton (’65, ’67), a retired attorney; and Joe Tipton, a retired Tennessee Court of Criminal Appeals judge. Joe’s granddaughter Margaret (Maggie) Grace Tipton, daughter of Hanson and Elizabeth Tipton, both of whom have UT degrees, will be coming to UT in the fall.

“Dr. Tipton was a role model in every way,” remembers Dempster Taylor. “Maybe the experience gave me confidence. You know, teenagers do need to be able to achieve something in order to feel that they’re able to go on to adulthood. My fondest memory, I suppose, was that first game when we found out that we were going to be pretty good at this and the work had paid off. That was very gratifying. And we thought we were being good ambassadors for the school. We’re approaching the 60-year anniversary for this experience. My teammates were very special people.”

ANSWERS

Toss-up No. 1: David C. Chapman quarterbacked the UT teams of 1894 and 1895 and is regarded as the Father of the Smokies. Mount Chapman and Chapman Highway are named for him.

Toss-up No. 2: Suddenly Last Summer. In The Glass Menagerie, the character Laura Wingfield is thought to have been modeled on Williams’s institutionalized sister, Rose Williams.

Toss-up No. 3: The Godfather Part II (1974).

Toss-up No. 4: In 1968, NBC broke away from the end of a game between the Oakland Raiders and the New York Jets to broadcast the film Heidi, prompting a deluge of calls. A new policy was born.

Toss-up No. 5: Harbrace is in its 18th edition. Some royalties still go to the UT English Department.

Toss-up No. 6: After CBS-TV sold Studio 52, it was turned into the super disco Studio 54.

—

Items from the scrapbook of Anne Dempster Taylor courtesy of the UT Libraries’ Betsey B. Creekmore Special Collections and University Archives. Photography by Morgan Phillips.

4 comments

I’m David Rubin’s little sister, and am even prouder of him today than back then, because each step in his academic life has led to another, better opportunity. Even in retirement, he has continued to teach, share information, inspire, and prod people to do more and do better.

Judith Rubin Martin

Just a fantastic story. What an odyssey for these outstanding students (and teacher). I especially enjoyed the follow-up stories that close out the article.

As a high schooler, I was somewhat aware of UT’s success on College Bowl, but in May of 1984 I had the privilege of meeting Joe Gorman and David Rubin. They were inducted as Alumni Members into Phi Beta Kappa. When they were students, UT did not have a PBK chapter and would not have until the late 1960s. I was a chapter officer and very much enjoyed my conversations with them

I was at UT Law with Harold Wimberley and in the same class for Torts. Disappointed that i made B, I went to Dr. DIX NOEL to find out why. He advised that there was one A and handed me Harold’s exam. I read it and had no further questions.

Comments are closed.