William Gibbs McAdoo

Imagine, if you can, a financial wizard with some engineering smarts who enabled the first subway tunnel under the Hudson River in New York. Then try to picture the same fellow, on the opposite side of the continent in Hollywood, teaming up with some of the most creative actors of the day to cofound the renegade film studio known as United Artists. Then try to think of the same guy in Washington, DC, where he’s secretary of the treasury during a major war, commanding the nation’s railroads in a way no other individual in US history has. Also, for good measure, becoming a US senator from California, running creditable and viable campaigns for president of the United States twice. Then picture him in jail in downtown Knoxville for his part in a deadly riot.

If there were such a person, surely you would know his name, but there’s a good chance you don’t. His name was William Gibbs McAdoo, and he was a UT graduate. The above is just a partial résumé. He also introduced electric streetcars to East Tennessee and played a major role in founding the modern Federal Reserve Board. His autobiography was called, appropriately, The Crowded Years.

William Gibbs McAdoo Sr

Despite the unusual name, UT’s story makes room for two William Gibbs McAdoos. The student’s father was a well-regarded UT professor. The elder McAdoo was a Mexican War veteran and lawyer who had been district attorney general before the Civil War. A Unionist with emancipationist tendencies turned secessionist after the war started—it wasn’t unusual in those harrowing days—McAdoo left Knoxville after Union occupation for Marietta, Georgia. William G., Jr. was born in 1863, soon after their arrival there. (Their house in Marietta, known as the William Gibbs McAdoo House—although they lived there only six months—is an honored historic landmark.) They later lived in Milledgeville, then the capital of Georgia. The McAdoos returned to a very different Knoxville in 1877, when the elder McAdoo was offered an adjunct professorship in history and English at the university, then run by former Unionist Thomas Humes.

The younger McAdoo finished public school at the old Bell House downtown and at age 16 was admitted to the college on the Hill—the same year it earned its designation as the University of Tennessee.

“I loved the university,” McAdoo later wrote in his memoir, The Crowded Years, which includes vivid accounts of that era. “As I look back upon that faraway time it seems to me that my life suddenly spread out and broadened when I became a college youth. All at once I had a wider range of interests. I read the newspapers, argued about public questions, took part in the dances, and reflected frequently and seriously on the ways of girls.”

In particular, he was active in Chi Delta, the debating society. He became infamous for taking the pro-Mormonism stance in a very public debate at the Opera House downtown.

He worked at UT’s experimental farm, already in operation then, and got a job at the US District Court, working out of the Custom House that still stands downtown. The young man impressed his superiors who recommended him for the position of deputy clerk of the United States Circuit Court for the Southern Division, Eastern District of Tennessee in 1882. He had intended to finish at UT and then study law, but at age 19, he suddenly had a respectable job with a respectable salary that offered another path to the bar.

He was at the beginning of an unparalleled career in which his intelligence, versatility, and resourcefulness repeatedly astonished his colleagues, but his three UT undergraduate years, fondly recalled in his memory, were the summit of his formal education.

At 22, he was admitted to the bar (a law degree was not required in those days) and worked for a time in Chattanooga, while staying in close contact with Knoxville. At 26, he began a complex attempt to establish the first electric streetcars in Knoxville, with a line from downtown to Chilhowee Park. It seemed promising at first. Knoxville was one of the South’s first cities to have electric streetcars—even before New Orleans, which became famous for them. But McAdoo encountered difficult technical issues and eventually gave it up. He moved to New York but kept ruminating about the failure and resenting the fact that another businessman had made an apparent success of the system he started. He came back with a reckless plan—to build a competing streetcar system, without city permission, which he knew would be denied. He hired hundreds of men to begin construction of the line on Depot Street, with a county judge on his side but the city police opposed, fomenting a bizarre riot that left one dead, and McAdoo, for a few hours at least, in the city jail on Market Square.

By then his professor father had died. He had other relatives in town—including his talented niece, impressionist painter Catherine Wiley, who was then a UT student known for her illustrations on college publications—but he returned to New York, where he made history with another more ambitious but very successful public-transit project: the first subway under the Hudson River to New Jersey, which he planned and financed.

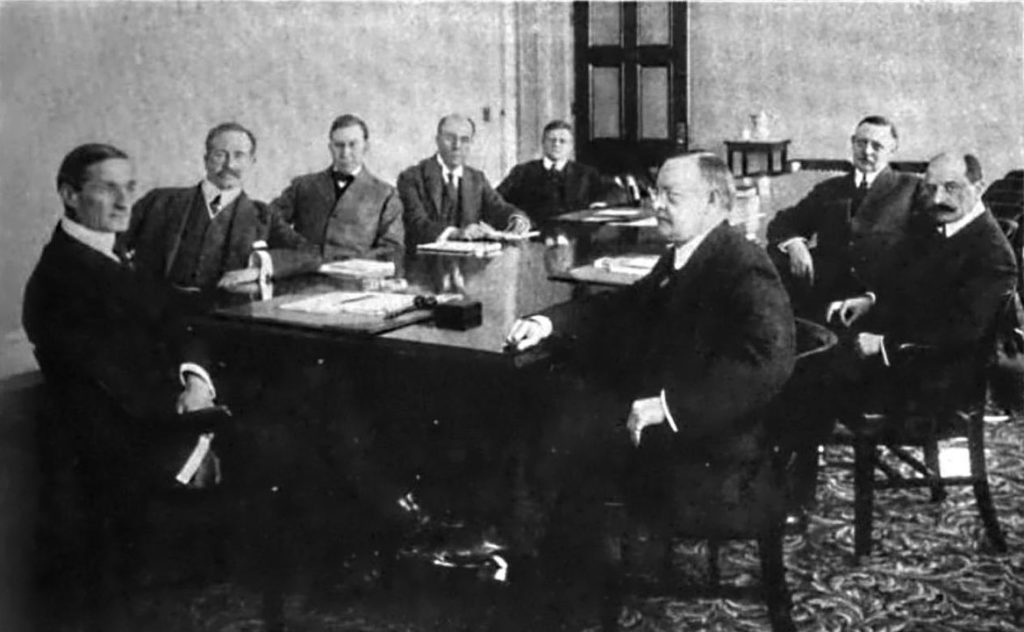

Federal Reserve Board with McAdoo on the left.

His first wife, Sarah, died in 1912, leaving him with seven children, some of them grown. By then he was working for the election campaign of Woodrow Wilson. Upon Wilson’s election, McAdoo became secretary of the treasury, a job he took just before the passage of the Federal Reserve Act.

In 1914, he married the president’s daughter, Eleanor. (The fact that Wilson’s son-in-law was his treasury secretary evokes lots of wry assumptions, but McAdoo had been a valued member of the president’s cabinet before he got to know Eleanor. Their first conversation was about the Federal Reserve.)

It was a dramatic and critical time to be secretary of the treasury. McAdoo was in charge of marshalling funds for a very expensive war in Europe and had the unprecedented responsibility of serving as a sort of wartime czar of the nation’s entire railroad system, coordinating it to best serve the war effort. McAdoo presided over the formation of the new Federal Reserve Board and served, in effect, as its first chairman.

Considering he retired in 1918, it may have been the most industrious five-year career of any treasury secretary.

In 1919 he founded a prominent law firm in New York, which still thrives today by a different name. He then moved to Los Angeles, an exciting new place that appealed to his creative mind. And here’s a point at which McAdoo seems to baffle historians. Political historians concern themselves only with things that happen in Washington. Likewise, Hollywood historians, perhaps not cognizant of his political profile, don’t recognize the name of the former treasury secretary. That’s why McAdoo’s thumbnail sketches often leave out his role in founding the renegade film studio known as United Artists. Famously it was Charlie Chaplin, Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford, and D.W. Griffith, the familiar show biz folks who bolted the developing establishment in 1919 to start their own studio where the actors and directors could maintain creative control. But they needed an innovative attorney and enlisted the former treasury secretary to make it work. McAdoo was not only their lawyer, but their partner, with a 20 percent interest in United Artists’ common shares.

McAdoo ran for the Democratic nomination for president in 1920 and 1924 and was considered a front-runner the second time. To cap off his “crowded years,” McAdoo, pushing 70, played a leading role in the nomination of Franklin D. Roosevelt for president in 1932, by throwing California’s previously dedicated votes to FDR. He then returned to public life, himself, when he was elected a US senator from California.

His crowded years ended, appropriately, in Washington, DC, where he was visiting for the third inauguration of Franklin Roosevelt.

The Hill has launched some remarkable careers, but it’s hard to top that one.

This story is part of the University of Tennessee’s 225th anniversary celebration. Volunteers light the way for others across Tennessee and throughout the world.

This story is part of the University of Tennessee’s 225th anniversary celebration. Volunteers light the way for others across Tennessee and throughout the world.

Learn more about UT’s 225th anniversary