Searching for the Right Questions, But Getting the Right Answers

On a November morning in 1995, I had an interview with Pat Summitt.

It was in her office. I sat on the famous sofa, where hundreds of Lady Vols had received advice, counseling, stern words, loving words. She sat across from me. Is there a word for the feeling of sitting across from a living legend, hoping not to embarrass one’s self? Of course, Summitt was friendly, open, and engaged. The glare, as many have said, was reserved for the basketball court. As she said many times, “Our players know that, when they step across the line onto the basketball court, the standard is perfection, and they accept that.”

Pat glanced at my No. 10 Reporter’s Notebook. My questions, scrawled on the brown cardboard inside flap, were about Michelle Marciniak, the flashy blonde point guard whose “spin move” to the basket—usually punctuated by an impertinent flourish of Marciniak’s ponytail—had been driving Pat crazy. It was decidedly not in the manner of Lady Vols basketball.

In an earlier interview, I’d asked Marciniak why she had Scotch-taped an AP photo to the dashboard of her Honda of Pat grabbing her jersey and yelling in her face. “I wanted to make sure that that never happens again,” answered Marciniak.

Is Pat being too hard on you? I asked. “Oh, no,” she said. “She’s trying to make me into the point guard that I can be.” At some point, Marciniak said, “I want a championship so bad it hurts.”

So now I was asking my questions to Summitt.

The warm-up: What should a point guard do? “Have the team in the palm of her hand,” she said. “She should be the coach on the floor.”

We talked about how Pat had first watched Marciniak as a ninth-grade AAU player but even then worried about how her flashy style would fit in with the Lady Vols’ system.

What about the AP photo? “Yes,” Pat said, smiling. “I called the Marciniaks and told them it wasn’t child abuse,” (As Lady Vols fans know so well, it was in the Marciniaks’ living room in Allentown, Penn., that Pat’s water had broken, causing her to quickly catch a plane home to make sure that Tyler was born in Tennessee.)

Why did you bench Michelle in the previous year’s title game against UConn? (She had whipped a long pass to a center, open under the basket, who let the pass go through her hands.) “We’ve been working on shortening our passes,” said Pat. “We want 12-foot passes, not 20-foot passes. Michelle knows [the center] can’t catch that pass.”

Pat glanced at my list of questions on the cardboard. “I see where you’re going with this,” she said, standing up and heading toward her side of her desk. I thought for a moment the interview was over. Instead the opposite happened. “That makes me think of something that just arrived today,” she said, cheerfully. She had given the team personality tests that Rodgers Cadillac gave its sales people to understand what motivates each individual. Summitt opened up the report and said that something had jumped out at her: basically, that she and her flashy point guard were exactly the same. More than anything else, they were both motivated to win, and they would do anything to achieve winning. Summitt said, in so many words, that this had given her a new perspective on how she had been relating to her point guard.

It should come as no surprise that an interview with one of the greatest coaches in history provided one of the most memorable moments for a humble reporter. But this was better than that. So much of Summitt’s coaching genius and personal willingness (and ability) to adapt to changing circumstances were laid out in the allegory of Spinderella and—it turned out, her Tough Love Godmother. That season was the story of Pat working with Marciniak, a psychology major, to get the most out of an introverted center who was shrinking more than most from Pat’s sterner coaching. It was also the story of Marciniak gathering the entire team on a sofa to explain to a freshman that she had been respectful of her elders long enough. For the team to win, she had to play like an All-American instead of a freshman. Happily, Chamique Holdsclaw did as asked, and the Lady Vols won the first of three NCAA titles in a row.

All this and more was told elegantly by, among others, the great Gary Smith in Sports Illustrated in 1998 and Sally Jenkins in the books she wrote with Pat.

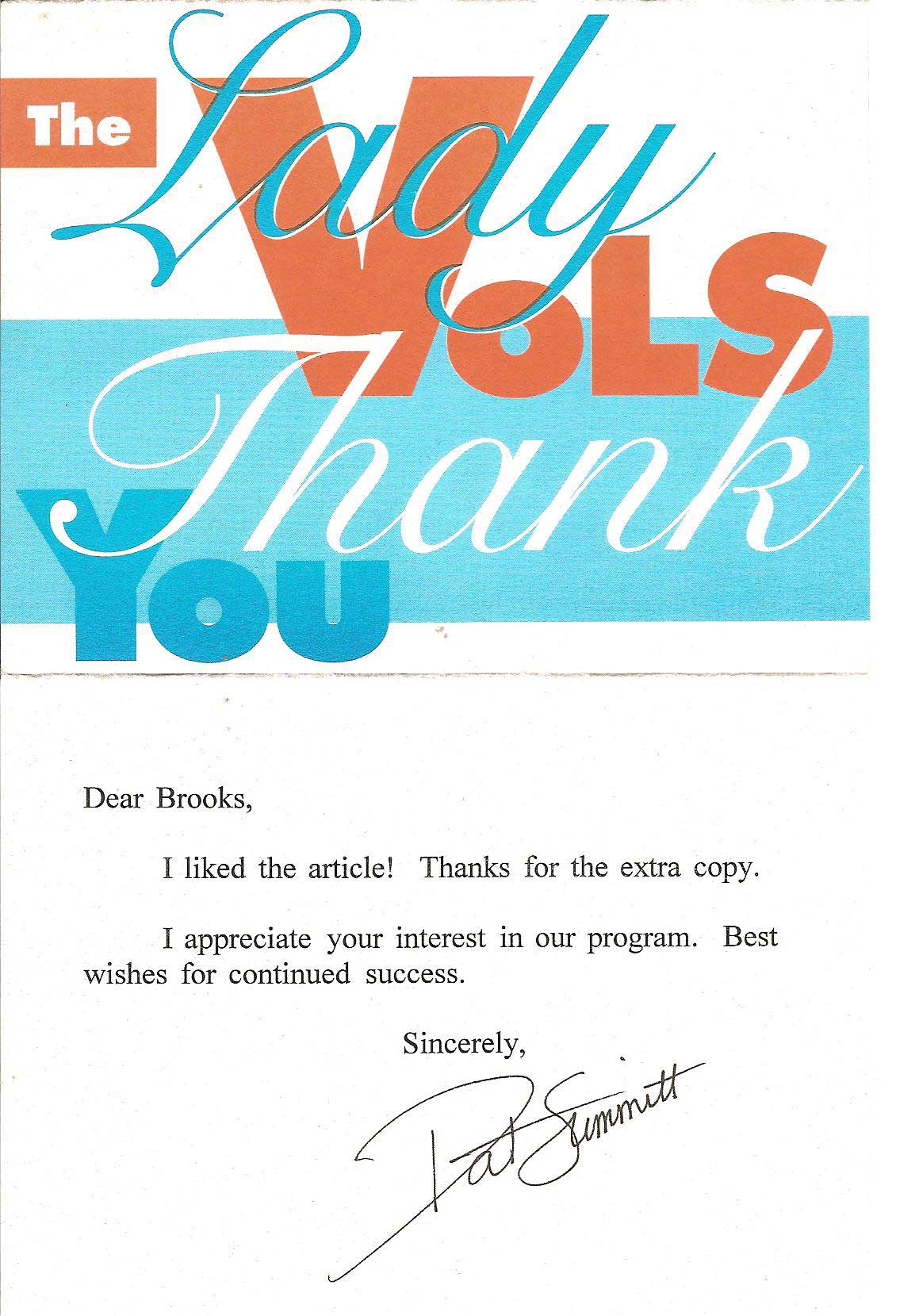

If you ever had a moment with Pat Summitt, you have remembered it and retold it in the past few days. Great coaches change lives and make the people they meet, not just the players they coach, better. And I’m grateful for having had that moment, when Pat helped me do my job better.

Brooks Clark is a project manager for alumni communications at the University of Tennessee—but in the ’90s he was Metro Pulse’s sports correspondent, often writing cover stories on UT athletics.

Originally published in the Knoxville Mercury.

1 comment

My husband’s uncle, John Head (yes, they are cousins) was among the first inductees into the Women’s Hall of Fame and the first man. Although his eyes were blue, Pat said he did not have the “blue-eyed stare”. I had to check-out the pictures in the Hall of Fame to verify. She was right. He shared the familial “man of few words” approach to life, so typical of the Head men. His coaching style did not include comfortations with the refs either; even in the Panama Games where National Business School ladies won.

Comments are closed.