When John Woodrow Kelley was seven, his parents took him to see the Parthenon in Nashville. “I fell in love with classical art and architecture and never looked back,” says Kelley. As an art history major at UT and then on his way to architecture and environmental design degrees at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, New York, he always “tried to squeeze in” studio painting classes.

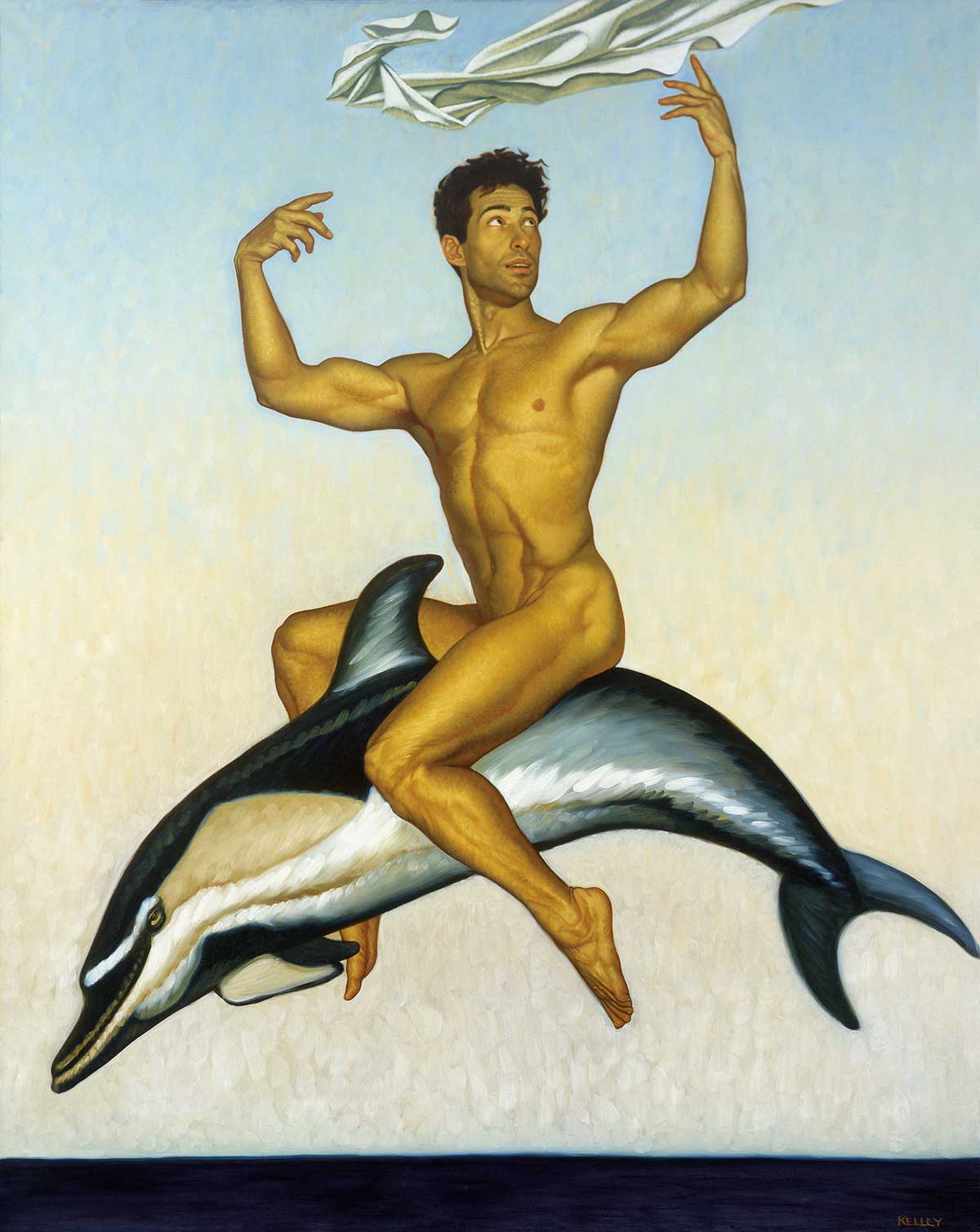

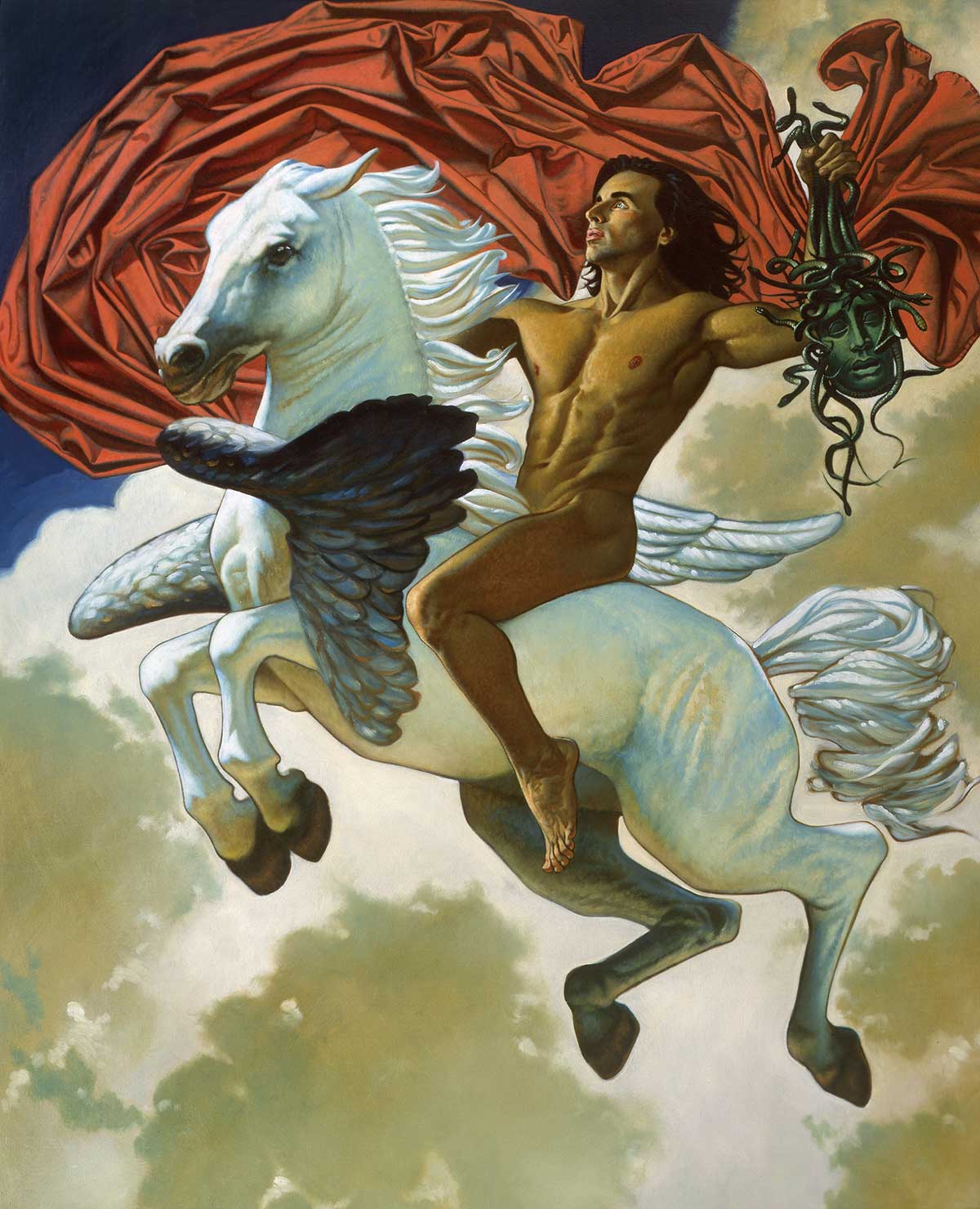

But Kelley had a problem. Swimming against the prevailing currents of abstract expressionism, he liked to express himself through the vocabulary of classical realism, echoing the ancient Greeks in his renditions of the human figure. “People would always say, ‘You can’t do that. That’s the old way,’” says Kelley. ‘We’re doing things the new way, abstract.’ I went right along and did it. I was just interested in something else, a return to reexamining the human figure.”

Today Kelley, tall and lanky, with short-cropped blond hair and small wire-rimmed glasses, is a successful and prolific painter. His painting Prometheus hangs in the Knoxville Museum of Art next to a work by Whitney Leland, one of Kelley’s favorite professors at UT. “How proud I am of that!” says Kelley, who two years ago through Jim Wells Productions published Greek Mythology Now, a book of a hundred of his paintings with a foreword by David Ebony, a contributing editor of Art in America magazine. “In each of Kelley’s images,” writes Ebony, “a certain tension arises between the classical context and the contemporary look of the figures, who are more often friends than professional models.”

Arion (Photo by Jim Wells)

Kelley splits his time between his Brooklyn studio and his family home in Knoxville, which—in line with his love of classical architecture—he has transformed from a sixties brick rancher into an Italianate stucco villa, complete with iron gates opening onto a stone courtyard, marble floors, and ornate fireplaces, decorated throughout with paintings of contemporary people looking like characters out of mythology.

Kelley can also do the traditional portrait. “Portrait commissions here in the South supported my continuing education,” he says. His portrait of Governor Bill Haslam as mayor of Knoxville resides in the City-County Building. His portrait of Roots author Alex Haley is in the permanent collection of the Tennessee State Museum.

But Kelley is most gratified that he has found other artists who share his classical vision. The Italian conceptual artist Carlo Maria Mariani, for example, paved the way for neoclassicists starting in the 1970s. “Seeing him in the Sperone Westwater Gallery in Soho changed my life,” says Kelley. “It was enabling for me. He was perceived as a surrealist, but his imagery was very classical, and he combined it with things that were contemporary. It was beautiful, and beauty had gone out of style with modernism. Everything was about grossing you out. Eric Fischl in New York has been painting the figure for twenty years. Now dozens of painters are doing it. That’s how a movement happens.”

Persephone (Photo by Jim Wells)

His artistic sensibility was piqued in art history classes at Webb School of Knoxville. “Mrs. Clover Waterman was one of the most important figures in my life,” he says. “She made us see art for what it is. She described the Mona Lisa as the masterpiece of Renaissance humanism that it is. It was empowering to learn about artists who used the human figure as a vehicle for expressing the contemporary world.”

Kelley started at UT in architecture but, done in by math, switched to art history, where he was influenced by Dale Cleaver, the department head; Rachel Patterson Young; and Professor Frederick Moffatt. On the painting side, Kelley remembers his painting teacher Whitney Leland. “He made an impression on me,” says Kelley. “He was very careful to teach us how to stretch a canvas, the importance of technique, stable glaze medium.”

Kelley got his UT degree in 1974 and his Pratt degrees in 1976 and 1978, respectively. He had a position at the architecture firm of Davis & Brody in New York, where he worked on modern buildings—because he had to. Just shy of his second anniversary, he quit to devote himself to his painting.

“I’m so grateful when I look back on this journey I have taken,” says Kelley, “fraught as it was with self-doubt and fear, and realize that I did do the right thing. I am a part of this new wave of interest in the figure. I’ve retained my belief in the validity of representationalism. The human figure is still a valid vehicle for the expression of the contemporary world. I was always taught that it was invalid. But it’s valid because it is a universal language. People respond to a human body because they occupy a human body. That is what artists have done for the past two or three thousand years.”

Perseus on Pegasus (Photo by Jim Wells)

1 comment

Thank you! My grandsons, great fans/grandmother-teachers of all characters mythological, will need to read and see both this article and John Woodrow Kelley’s book.

Comments are closed.