During his storied career, printmaker Beauvais Lyons has done some incredible things. By the age of 25, he had documented two previously unknown civilizations. Later, he worked on the reconstruction of an ancient temple, helped to bring the bones of a centaur to the university, and discovered a few new hybrid animals.

If all this sounds kind of odd for someone who heads up UT’s printmaking program in the School of Art, then you’re no April fool. Parody, hoaxes, and pranks are Lyons’s specialty.

If all this sounds kind of odd for someone who heads up UT’s printmaking program in the School of Art, then you’re no April fool. Parody, hoaxes, and pranks are Lyons’s specialty.

To a certain extent, Lyons has done all of these extraordinary things through his art and his teachings at the university. In particular, his work with the Hokes Archives—which bills itself as “the fabrication and documentation of rare and unusual artifacts”—and his freshman pranks class have brought about some of these spectacular marriages between creativity and mischief.

As an undergraduate at the University of Wisconsin–?Madison, Lyons’s thesis exhibition displayed ceramics and prints that he created to document an imaginary dystopian culture from north-central Turkey called the “Arenots.” His graduate studies at Arizona State University culminated in an exhibition called “The Excavation of the Apasht” and documented a plausible—yet imaginary—culture from the “Hindoo Kush” region of Afghanistan.

While Lyons utilized printmaking as well as ceramics in his art, it was aspects of printmaking that most intrigued him.

“What interested me about printmaking is its capacity to combine the handmade and the photographic,” Lyons says. “As I continued to work in it, I began to appreciate its history, especially for the scientific and technical publications.”

Lyons came to UT in 1985 as an assistant professor of art. He found the printmaking program had an advocate in his predecessor Byron McKeeby. McKeeby’s untimely death the year before Lyons’s arrival left some big shoes to fill.

“I have tried to build on what he envisioned for the program,” says Lyons, now the James R. Cox Professor of Art and a Chancellor’s Professor. “Of course, printmaking has changed in many ways.”

For Lyons, the use of color inks, photo-mechanical processes, variable editions, and the integration of computer and traditional methods are part of a natural evolution, but he still pays homage to McKeeby with the inclusion of drawing in the discipline.

The commitment of Lyons and his colleagues has paid off in a big way for students and the university. U.S. News and World Report currently ranks the printmaking program fourth in the nation.

The Hokes Archives

Outside the classroom, Lyons is the self-appointed director of the Hokes Archives, which includes his mock-archaeological projects about the Arenots, Apashts, and Aazudians; art from the George and Helen Spelvin Folk Art Collection; Hokes Medical Arts; and the Association for Creative Zoology. His one-person exhibitions have traveled to more than fifty galleries and museums and have been featured in many academic journals, as well as People magazine.

The Spelvin collection (“George Spelvin” is the fictitious name used in a theatre program when an actor is playing two parts) includes folk art and fictitious narratives of the people who made them, like Juanita Richardson and her painted beer bottles. Her art came about after the loss of her uncle and father to alcoholism. She believed if the bottles became art,they couldn’t contain alcohol anymore.

The Hokes Medical Arts include many elaborate, color lithographs for English, American, French, and German publications. These prints detail portions of the human anatomy that look as if Dr. Grey took notes from Dr. Seuss.

The Hokes Medical Arts include many elaborate, color lithographs for English, American, French, and German publications. These prints detail portions of the human anatomy that look as if Dr. Grey took notes from Dr. Seuss.

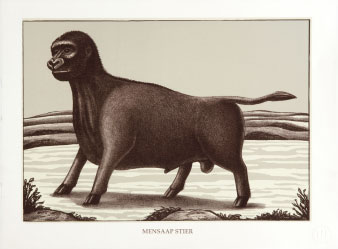

Along the same lines, the Association for Creative Zoology takes a deep look at the theories of evolution and creationism. Detailed prints, photographs, and taxidermy show animals such as the “Groundhog-fish” (a fish with a groundhog’s head) and the “Vos Arend” (a bird with the head of a fox).

“All this fakery is a mask that allows me to address truths in one way or another,” says Lyons. “Art holds up a mirror to our society. People slow down and reflect more deeply about things they don’t understand or are aren’t sure of. I want art to be a speed bump.”

In 2007, Lyons gave his mock-academics a theatrical flair when he set up a kiosk for the Association of Creative Zoology at the annual Scopes Trial Festival in Dayton, Tennessee. He acted as a member of the association’s original street display from the 1925 trial that debated evolution and creationism.

The Art of the Prank

It was the theatrical aspects of his art that gave Lyons the idea to create a class at UT in which students are the pranksters. Despite how much this class may sound like some of Lyons’s mock-academics, it’s very real and very popular.

For five semesters, students have been practicing the art of the prank by composing prank letters to corporations and government representatives and inventing and advertising student organizations such as “The UTK Urine Drinking Club” and the “Facebook Addiction Support Group.”

“Pranking has a long tradition as part of college life. Indeed, one might assess the quality of a university in terms of a ‘pranks index,’” he jokes. “Columbia University, MIT, and Cal Tech are all known for the quality of their pranks. If we really want to achieve our Top 25 objectives, maybe we need to establish an institute devoted to prank studies?”

While pranking may sound like all fun and games, it can be looked at academically. Last year, Lyons was asked to chair a session at the College Art Association Conference in New York on “Pranks and Art” that was featured in the December 2011 issue of ARTnews. The session sought to develop a theoretical framework for pranks as a form of art.

The theory is certainly something Lyons has advocated for through the Hokes Archives. He played a large role in bringing the skeletal remains of a centaur to Hodges Library. The specimen, originally made by Bill Willers, a zoologist from the University of Wisconsin in Oshkosh, is part of a permanent exhibit with a display plaque that asks the viewer, “Do you believe in centaurs?”

All in all, it’s a very telling question that could be asked of a lot of Lyons’s work. Do you believe?