Mary Cayten Brakefield calls it the first big accomplishment of the day. Getting out of bed, slipping on a favorite dress, knotting a belt around her waist, then buckling the straps of her leather heels before heading out the door.

“Every morning being able to make that choice about what you want to wear, not just because it’s what fits but because you love how it looks, makes you feel like you can go out and conquer the world,” says Brakefield, a retail and consumer sciences grad and former Lady Vol swimmer.

As she grew into her tall, muscular frame, shaped by years of volleyball, swimming, and other sports, Brakefield often felt constricted in her clothes. As she got older, she realized it wasn’t just her. Every body changes—but sometimes it happens in ways you don’t expect.

Brakefield was a sophomore at UT when she met Indian swimmers Shams Aalam, who is paralyzed from the waist down, and Justin Jesudas, who has no feeling or control below his chest. Both men use wheelchairs. Both travel the world representing their country and have won gold medals. Why should they have such a hard time finding clothes that function properly for them? Brakefield, who had been sewing since age six and making her own clothes since high school, was determined to find an answer.

The mission became even more personal that same year when Brakefield got sick. One day, after swim training, she passed out and convulsed on the floor of the locker room. Concussions, infections, and a variety of other afflictions followed. For two years, she was in and out of the hospital as doctors tried to figure out what was wrong. After her heart rate dropped to dangerous levels, a pacemaker was implanted in her chest (she calls it “Sparky”). Eventually doctors diagnosed her with Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome and dysautonomia.

Brakefield could have crumbled but didn’t. Though the diagnosis cut short her dreams of competing at a higher level—before coming to UT she qualified for the US Olympic Trials in the 100-meter backstroke—it strengthened her resolve. The waves she faced were different now, but she raced into them head on, moving forward stroke by stroke.

“I thought I would swim for longer,” Brakefield says. “That’s taken some time to come to terms with. As much as I wanted that, I wouldn’t trade it for what I’m working on now for a million years.”

At the time Brakefield met Aalam and Jesudas, she was participating in the VOLeaders Academy, a leadership development program for UT student–athletes. Over and over that year, she listened as the academy’s instructors said, “You’re more than just your sport. Your sport is just a vessel.” The overarching question they asked every participant to consider was “How are you going to use your talents and your platform to make people’s lives better?”

While recovering from the worst of her illness, Brakefield started connecting the dots. She understood the need for adaptive clothing. She had the skill set as a designer. And she had the foundation in leadership and service that VOLeaders had provided her. “What if this is what God put me on earth to do?” Brakefield wondered. Then, as swimmers do, she dove in.

Above: Mary Cayten Brakefield (at right) with her mother and business partner, Stephanie Brakefield.

“She had a vision, with her mom, of what she wanted to do,” says Michelle Childs, associate professor of retail and consumer sciences and director of graduate studies. Childs also noticed Brakefield’s determination after having to medically retire from swimming.

“She had mountain after mountain after mountain in front of her,” Childs says. “And she still showed up with her game face on every single time. She jumped into every project. And a lot of these projects were voluntary—she didn’t get class credit. And she stayed positive.” She did what she’d always done in the pool: she worked and worked and worked until she got where she wanted to be.

And Brakefield was creative about supplementing her knowledge. “She was one of those students looking around the university for anything related to what she wanted to do,” says Bill Black, a recently retired costume designer who taught and directed design for more than 200 Clarence Brown Theatre productions.

One day Brakefield showed up in Black’s pattern-making class, which normally has a prerequisite that Brakefield didn’t meet, but she persuaded him to let her in. Often she’d show up to Black’s class with an idea, a fabric, and a question: “What do I need to know to make this happen?” The next week, she’d pull up pictures of the frock she had made for Black to see. “She’d show up with some wild piece of fabric, and I’d wonder, ‘How did you even find that?’ And she’d always work it out.”

During her senior year, Brakefield pitched the idea for an adaptive fashion line at the Graves Business Plan Competition; she won third place in the lifestyle category. A few months later, she was awarded $10,000 in seed funding through the Boyd Venture Challenge, another competition organized by the Haslam College of Business. Her success led her to be selected to represent UT at the SEC Student Pitch Competition.

“There’s a lot of pitches you hear where people come up with a solution before they think of the problem,” says Lia Winter (’19), Brakefield’s coach for that competition and an entrepreneur-in-residence in UT’s Anderson Center for Entrepreneurship and Innovation. She had seen Brakefield pitch at the Graves competition and suggested to college leadership that she should be their nominee for the SEC competition.

“Mary Cayten has experienced the problems herself,” Winter says. “So when she speaks about the current options that people with disabilities have for clothing, it’s just striking how much of an opportunity there is. It just makes a lot of sense.”

In September 2021, Brakefield and her mother Stephanie Brakefield, who is also her business partner, debuted a line of adaptive clothing at Fashion Is for Every Body, an inclusive runway show in Nashville. Their bright, colorful prints were featured on models of different sizes, colors, and abilities. Brakefield had gotten attention on social media a year earlier after posting a photo of one dress she made on herself and another woman. “How could someone who is almost six feet tall, like me, and someone with dwarfism both wear the same dress?” she asked a Knoxville news station. The answer: buttons that allow the wearer to adjust the tiers in the skirt.

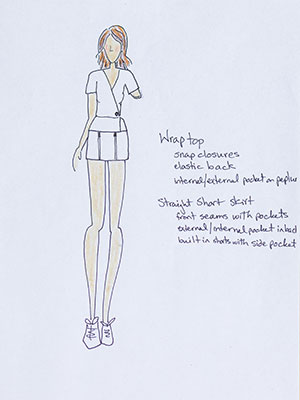

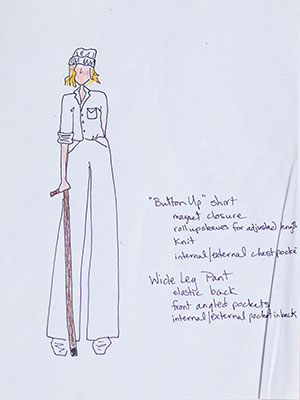

This summer, with the feedback from dozens of women whose experiences and preferences they’ve collected, Brakefield’s LLC is releasing its first public collection, which includes a dress, skirt, blouse, belt, and earrings. Each item has adaptive features such as pull tabs for those with limited use of their hands, allowing them to hook a finger or tool through to pull their clothes on and off, and dual access pockets for easily, safely, and discreetly storing and using devices attached to the body, such as an insulin pump. But there are others that Brakefield describes as “less obvious but no less intentional,” like the stretchiness of the fabrics, necklines and dress shapes that allow for easy access for bathroom trips and medical devices, clip-on options for earrings.

To research what women with disabilities want, Brakefield turned to Instagram. She looked for advocacy and support group pages and followed the people they tagged and followed. “I cold DM’d people constantly throughout the day,” she says, asking people like Allie Schmidt, who has ALS and runs the Disability Dame, a blog and resource for parents living with chronic illness and disability, if they were interested in talking about their clothing choices. “I almost got my Instagram shut down because they thought I was a bot,” she adds, laughing. “It’s grown very organically.”

Schmidt had gotten a message on LinkedIn from Brakefield asking if she had issues with her clothing.

One of the hardest parts of having a disability is not being able to find clothes that can work with your needs.”

She connected Brakefield to other women in her circle who had Crohn’s disease, diabetes, and ALS. Brakefield asked Schmidt to film herself trying on regular clothing, so she could see where the difficulties were. Brakefield and her mother would then go to Schmidt’s house and have her try on different designs they made.

“We basically met over and over again, and they just kept refining the clothes to make sure each time it was getting easier to take on and off,” Schmidt says. During one of their meetings, after experimenting with replacing buttons with magnets, Schmidt suggested they scrap fasteners from their clothes altogether: “They’re going the extra mile to really make sure that you’re conserving your strength.”

And, of course, to make sure the clothes look fashionable. “A lot of marketing for products that people with disabilities can use is focused on the elderly,” Schmidt says. “It can really impact your self-esteem when those are the only products that are available to you. Just because you’re disabled doesn’t mean you don’t also want beautiful things. You want to feel just as confident as the next woman.”

Brakefield’s designs explode with color. They’re meant to evoke joy. The custom-designed prints come alive with pinks and reds, greens and blues. They’re fashionable, representing the brand’s aesthetic. But they’re also functional; the prints for her summer line were chosen because of how well they hide stains from fluids.

Brakefield knows her niche. “We’re a very feminine, very colorful, print-based company,” she says. There’s plenty of room in the market for other companies to come in and share their own perspective on what fashion for different body types and abilities can look like. “We don’t want to block out the competition. We want to support more and more brands coming in so that people can choose rather than having to just buy what functionally works.”

Brakefield has been on both sides of the fence when it comes to choice. Some days as she sews upstairs in the studio that was once her older brother’s bedroom, she thinks about it. If she wanted to, she could move to New York or Los Angeles and get a job in the fashion industry. Or she could switch lanes again. She’s been coaching kids in Nashville on the swim team she was once part of, leading as she once was led. She could simply keep making clothes for herself. But maybe—a thought she always finds herself coming back to—it all happened this way for a reason. Maybe swimming really was just a vessel, as VOLeaders taught her. Maybe fashion is a vessel. Maybe all this time, Brakefield was being prepared simply to be a person with the skill, the commitment, and the attitude to actually make a difference.

“There’s so many women we’ve gotten to know over the past two years who’ve shared their stories and their encouragement with us,” she says. “That’s what keeps me going. Because universal design should be the norm. We’re excited to help make that shift in the industry.”