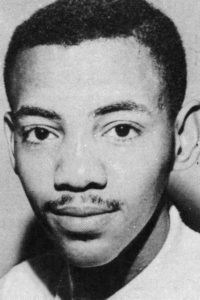

Theotis Robinson Jr., Charles Blair, and Willie Mae Gillespie were UT’s first admitted black undergraduates in January 1961.

For most of its history, the University of Tennessee had an all-white student body. In 1954, the US Supreme Court struck down the 58-year-old doctrine of separate but equal, effectively banning racial segregation in public schools. For the next few years, school systems all over the South delayed the process as much as possible. The region’s all-white colleges and universities were not directly affected by the ruling, but throughout the 1950s they showed wavering signs of quiet resistance and grudging acceptance, depending on local and state politics. The climax of Southern university desegregation came in the early 1960s with rancorous confrontations and even riots on campuses of the Deep South. The white leadership of the University of Tennessee was reluctant, but its path to racial integration was quieter and less acrimonious.

Gene Mitchell Gray, First Black Graduate Student.

In the 20th century Tennessee had always seemed the picture of Southern moderation, but it was nevertheless a Jim Crow state with an unbroken record of enforced white supremacy. Most spaces, by public and private sector, were strictly segregated, and after World War II, Southern segregation was beginning to look like a blatantly antidemocratic institution—even to some Southerners who had grown up with it.

In 1952 UT embarrassed itself by forcing five academic conference attendees to sit separately in Sophronia Strong Hall’s cafeteria because of their skin color. In September 1955, Time magazine gave grades to the states undergoing the process of de-segregation. The five states of the Deep South were given Fs, while Missouri was the only state awarded an A. Befitting its history of lukewarm politics, Tennessee (along with Delaware) received a C.

Like elsewhere in the South, UT was desegregated because of a grass-roots movement led by black Southerners, many of them Knoxville natives. Between 1940 and 1950, Knoxville’s black population rose by more than 19 percent, and with it demand for new educational opportunities.

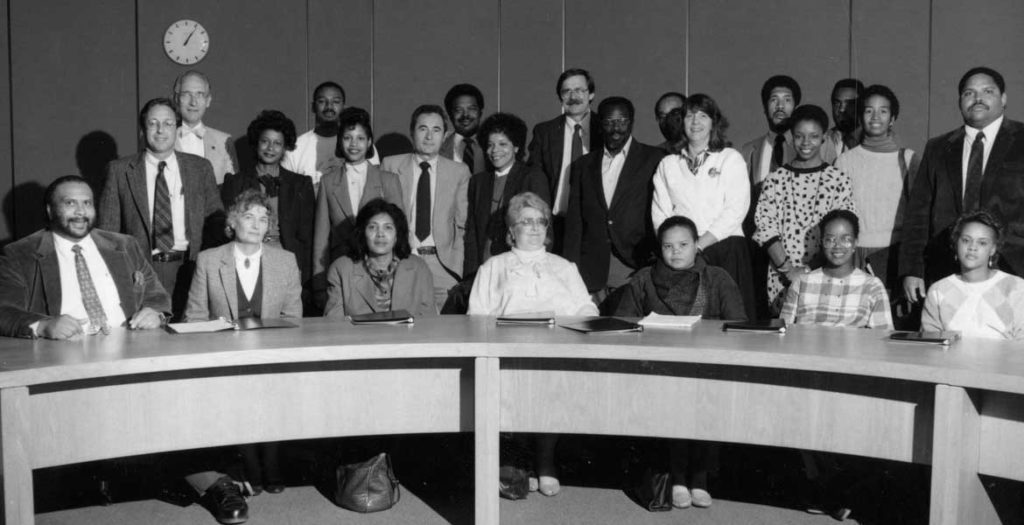

Sammye Wynn became the first black instructor in the College of Education in 1967. That same year, Robert Kirk became the first full black professor at UT, teaching health and safety.

In 1950, Gene Gray and Jack Alexander (applicants for UT’s Graduate School) and prospective law students Lincoln Blakeney and Joseph Patterson hired a Knoxville law firm to challenge the state’s lack of graduate education for black students. Gray and his co-plaintiffs won and, by 1955, 68 black graduate students were enrolled at the Knoxville campus. Lillian D. Jenkins became UT’s first black recipient of a graduate degree, earning an MS in special education in 1954, and R.B.J. Campbelle was the first black graduate of UT Law in 1956. Three years later, Harry Blanton became the first African American to earn a UT doctorate. Interviewed years later, Blanton remembered no active scorn from his classmates but instead the feeling of being “the invisible man on the campus.”

As the 1950s drew to a close, undergraduate education remained segregated. Tennessee Governor Frank Clement favored school desegregation in principle, but he was unwilling to flout the wishes of the conservatives in the legislature and board of trustees and Clement et al decided in 1955 to postpone the desegregation plan indefinitely. Hoskins and Brehm had no interest in desegregating the student body, but the obvious inequality was beginning to embarrass them, especially since more and more UT faculty members were vocal integrationists.

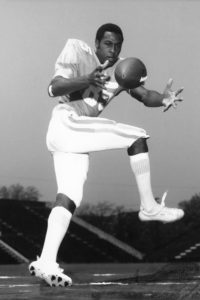

First Black Football Player Lester McClain.

Meanwhile, Knoxville restaurants, hotels, and practically every other public space in town were segregated. In the spring of 1960, Knoxville College students initiated a massive protest outside downtown businesses that limited or prohibited black customers. That same summer, activist Theotis Robinson Jr., a recent graduate of all-black Austin High School applied to UT but was turned down. The young man managed to schedule a meeting with President Andy Holt, informing him that he had a right to attend UT by virtue of being a Tennessee citizen and a taxpayer, and he and his family were prepared to take legal action.

Holt did not immediately relent, but Robinson’s assertive meeting was the beginning of the end of all-white education on the Knoxville campus. Soon thereafter state attorney general George McCanless told Holt that the school no longer had a legal basis for maintaining segregation.

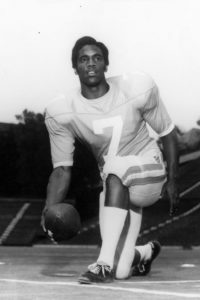

Condredge Holloway First Black Quarterback and Shortstop, All-Century Player.

In January 1961 Robinson enrolled as a student alongside two other black classmates, Charles Blair and Willie Mae Gillespie. It was among the first such moments in the history of university integration, and (perhaps because the new students were unceremoniously enrolled in the middle of a school year) one not met with the level of notorious white resistance seen in Georgia (where there was anti-integration rioting on the very same winter day when Robinson, Blair, and Gillespie enrolled), Mississippi, and Alabama over the next three years. But desegregation at UT did not equal integration; Robinson, Blair, and Gillespie ate separately from other UT students and did not live on campus. Robinson later recollected that he in no way depended on UT for a social life, and that years later, black students who did live in dorms recounted “horror stories” of bigotry, and that black men attending inter-racial off-campus parties had been arrested. And, due to resistance from UT athletic director Robert Neyland, black students were not allowed in UT intercollegiate athletics for a number of years to come.

Meanwhile, Brenda J. L. Peel, a Knoxville College transfer became the first African American to receive a bachelor’s degree in 1964. The next year UT became only the second university in the entire country (after the University of Miami in Florida) to conduct desegregation training for Tennessee public school teachers. And, in 1967, Health & Safety professor Robert Kirk became UT’s first black faculty member. In the Civil Rights Era, the University of Tennessee exhibited reluctance but also leadership.

1 comment

The fanbase doesn’t know Neyland’s history https://www.volnation.com/forum/threads/neyland-stadium-name-change.334274/