On September 10, 1794, at the edge of the American frontier, a spark of an idea was kindled. That flame has grown into a beacon that continues to grow stronger.

What began as Blount College centuries ago is now Tennessee’s flagship university and premier public research institution, and Volunteers have been lighting the way for others, in Tennessee and throughout the world, for 225 years. Today, UT educates more students, conducts more groundbreaking research, and receives more support from stakeholders than at any other time in its history.

In 1794, Knoxville was the capital of the Southwest Territory and Blount College was the first public institution chartered west of the Appalachian Divide, two years before Tennessee was officially declared a state.

Samuel Carrick

Blount College’s president and sole faculty member, Samuel Carrick, was the first in a history of leaders committed to the idea of higher education in Tennessee, despite seemingly insurmountable challenges. The story of the university is one of perseverance and patience. UT’s success is built on persistence and hard-won victories laid atop one another for 225 years.

In the intervening years, the institution overcame funding shortfalls, disputes over religious affiliation, resignations of presidents, and disagreements about the tuition and curriculum. UT’s progress was stopped in its tracks as the nation—and the campus, which closed in 1862—was ripped apart by slavery and secession.

Thomas Humes, UT’s 10th president, reopened the college in 1866 and great strides were made to reorganize and rehabilitate the war-torn campus. Several new buildings were constructed, new faculty were hired, and 10 years later, enrollment was at a record high.

The university was again transformed following its land-grant designation in 1869 thanks to the federal Morrill Act, which sought to make education available to all. The Herbert College of Agriculture, AgResearch, the College of Veterinary Medicine, and UT Extension are all direct results of the Morrill Act and other legislation. In 1879, the state legislature designated what was then East Tennessee University as the University of Tennessee.

Under the tenure of Charles Dabney at the turn of the 20th century, UT received its first direct appropriation of funds from the legislature. Dabney directed significant changes to the course of study and insisted that university schooling must prepare young people for an active—not contemplative—life. By the early 1900s, record numbers of faculty, staff, and students—which now included women—were involved in the studies of agriculture, mechanical arts, mining, engineering, law, and military instruction.

New Traditions

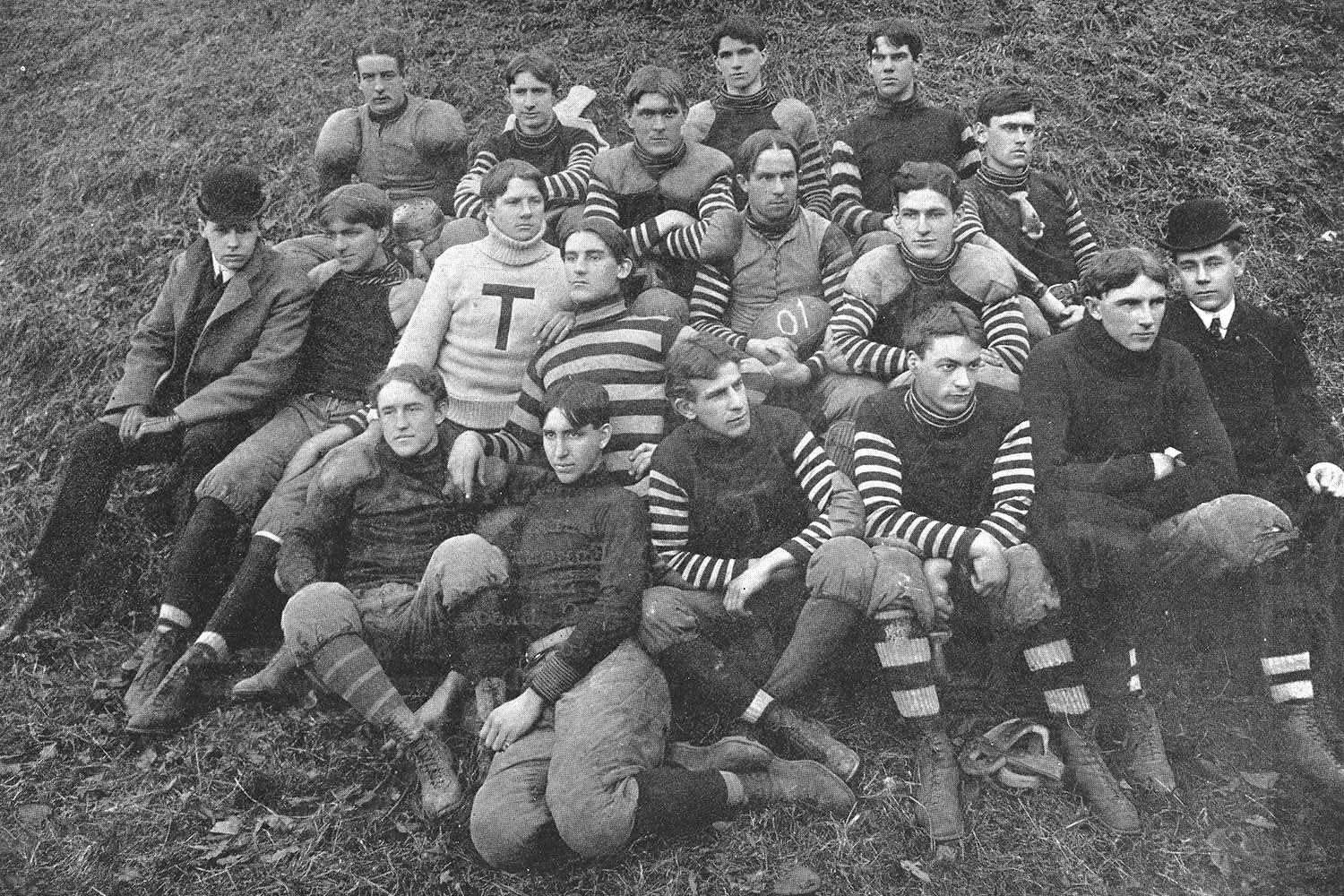

It was around this time that many of UT’s traditions began to form. After a heated student debate, Tennessee’s colors were officially named orange and white in 1894. The UT football team was called the Volunteers for the first time in 1902 when the Atlanta Constitution reported on a football game between UT and Georgia Tech.

The state owed its nickname—the Volunteer State—to the large number of volunteers who fought in the War of 1812. At the start of the Mexican-American War in 1846, 30,000 Tennessee volunteers responded to the secretary of war’s call for 2,800.

As UT’s athletic reputation grew, the Volunteer became the bedrock of the university’s identity.

In 1921, UT completed work on Ayres Hall and added an engineering building, two women’s dormitories, Cherokee Farm, land along Cumberland Avenue, and Shields-Watkins football field.

The forerunner to Torch Night, the freshman pledge ceremony, was first held in 1925. Soon after, Aloha Oe began, and “On a Hallowed Hill” was adopted as the alma mater.

By 1932, UT had adopted the Volunteer Creed—“One that beareth a torch shadoweth oneself to give light to others”—and the university’s official symbol—a man holding a torch high in his right hand and the Goddess of Victory in his left hand.

Modern Era

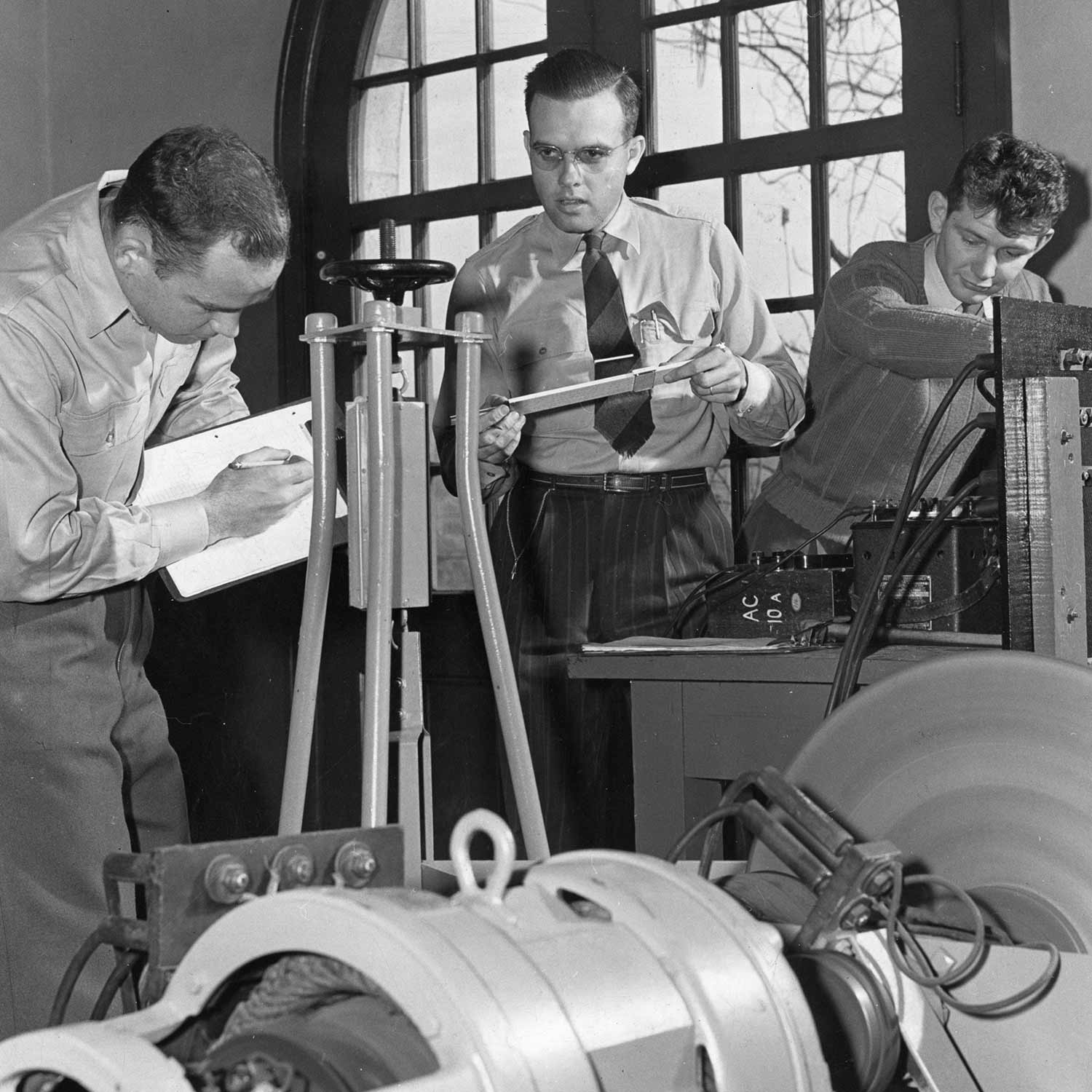

In 1942, UT and Oak Ridge National Laboratory—then called Clinton Engineer Works—created a collaboration that continues today to shape the frontier of modern scientific research.

During the Manhattan Project, a number of UT faculty worked at CEW, including six engineering faculty members and a physics instructor. After the war ended, the UT Board of Trustees responded to the increased enrollment of veterans by offering new PhD programs in chemistry, physics, and English. A new program was established to offer graduate courses at the Knoxville campus and in Oak Ridge.

While UT was modernizing on many fronts, it still lagged behind in its policy on admitting black students. As elsewhere in the South, UT was desegregated because of a grassroots movement led by black southerners.

UT’s first black graduate student, Gene Mitchell Gray, was admitted to study chemistry in the winter quarter of 1952. His admittance followed a lawsuit in fall 1950 when he and three other students sought admission to the university’s graduate programs.

After a judge in federal district court upheld their right to admission but did not issue an order, the students took their case to the US Supreme Court. UT changed its policy, admitting Gray, so the Supreme Court declined to act.

Theotis Robinson Jr., Charles Blair, and Willie Mae Gillespie were UT’s first admitted black undergraduates in January 1961.

Growing Campus

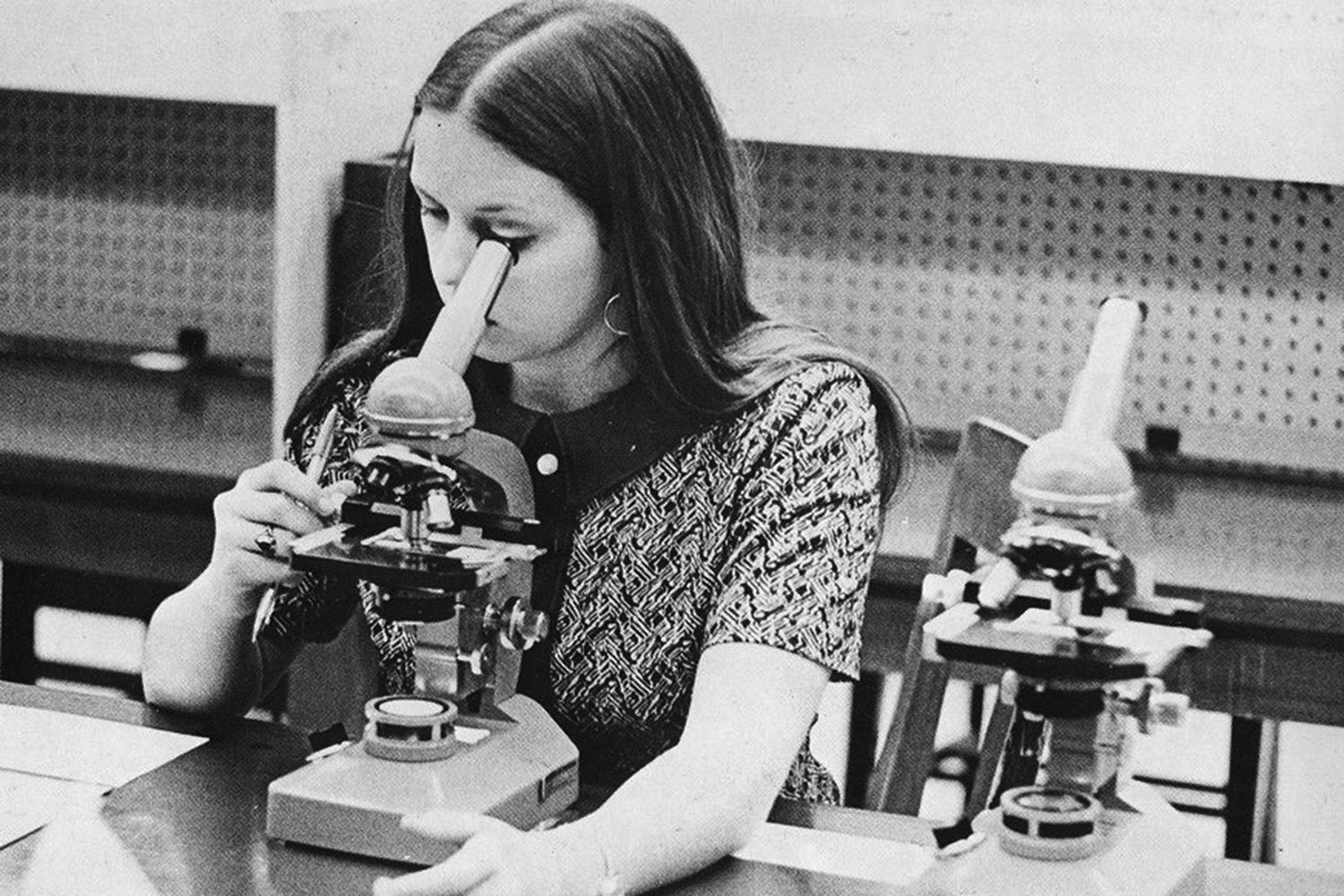

Into the 1960s, under the leadership of Andy Holt, student enrollment tripled, faculty and staff doubled, eight new buildings were added, and the west side of campus was developed. In 1968, UT underwent an administrative reorganization that made the Knoxville campus the flagship and headquarters of the new UT System.

UT’s reputation as an athletic powerhouse continued to grow in the last quarter of the 20th century. The university holds eight women’s basketball national championships and six football national championships. The men’s swimming and diving team and track and field programs have won national titles and fielded Olympians.

During this time, the university’s research work was also gaining attention. UT achieved its first designation of producing the highest level of research activity from the Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education. The university received R1 status in 1973, the first year that Carnegie began classifying research institutions.

In 2018, UT had a record $260 million in research expenditures. Faculty members are working to understand life on other planets, help the Air Force travel at five times the speed of sound, and develop strategies for advancing STEM education in Appalachia.

The university engages some of the world’s top scholars and students in the quest for solutions to complex global issues. It is the hub of a vibrant research community that includes 11 colleges, major private industry partners, federal agencies, local companies, and student start-ups.

Additionally, in all the colleges, students see the creative spirit at work and at play, igniting lifelong passions for authenticity and expression. Fueled by curiosity, Volunteers are using their understanding of the natural world and human experience in creative endeavors.

Volunteer Spirit

In 2015, UT earned the Carnegie Community Engagement Classification for collaborating with community partners to address society’s most pressing needs. At the time, UT joined a group of just 52 universities with a very high intensity research classification and an engaged status designation.

Around the world, more than 250,000 proud Volunteers share their light within the communities where they work and serve. A record 47,000 donors gave to UT last year, helping the university meet its $1.1 billion Join the Journey campaign goal two years early. This campaign has created 857 undergraduate scholarships, 303 graduate fellowships, and 159 faculty awards, professorships, and chairs.

With every Tennessean who finds a path to their future at UT and every graduate who crosses the stage at commencement, the spark of 1794 glows even stronger. Each Volunteer carries with them 225 years of showing up to answer a call, building a tradition of excellence in teaching, research, scholarship, creative activity, outreach, and engagement.

Volunteers have been working together to light the way for others, through service and discovery, for 225 years. The light of this university is seen in every corner of Tennessee and throughout the world—a beacon shining bright.

5 comments

Re: “the T-shirt” and the full scholarship… WELL DONE!

I don’t know anything else about UT but, henceforth, I will be aware and note when I hear anything about the university. I’m a new fan.

This is a great account of UT History. I attended UTK during 1961-64, graduating with a Bachelor of Science in Chemistry. God continue to bless our hallowed university!

UT College of Liberal Arts gave me the best education around. Because of the mandatory classes in the curriculum, I took courses that I would not have chosen, but “Liberal Arts” then meant exactly that and the university was committed to educating the whole person. Dean Nielsen was outstanding and knew me, my roommate, and many of my friends by name. The quarter system with the mandatory five academic classes per quarter was very challenging and emblematic of UT’s academic standard. I learned so much and have been forever grateful for UT’s excellence. When Dean Nielsen gave me my sheepskin at graduation, he said, “Congratulations, Jean. I am just so proud of you.” He knew my name. And, all Liberal Arts students had to pass the swimming test to graduate! I received an outstanding education for a low cost, including living in the dormitories. Thank you, my Alma Mater!

It is Reverend Samuel Carrick, minister of the Old Presbyterian Church, still meeting in downtown Knoxville on what was Carrick’s turnip patch. This is yards away from Blount College, named after Teritorial Governor and signer of the Constitution, William Blount on land given by Knoxville founder James White.

It is not accurate to say, “…for 225 years,” since the school was closed from 1809-1820 after the death of Carrick, and again during the 1860s, as you mentioned.

Thank you for this. I grew up in Knoxville and have a Master’s from UT but didn’t know much of the history.

Comments are closed.