If you went to elementary school in a certain era, you might have seen a map of a fictitious place drawn to illustrate all the basic geographic features. UT’s campus is almost like that. There’s a famous river; a peninsula; a couple of knolls, not counting an Indian mound; a bit of a ridge; a sharply defined valley; some remnants of dense woods; two creeks; and some rock outcrops. Geologists and builders know that under the surface of campus are extensive caves. And, of course, there’s a Hill.

It’s not surprising that hallowed hill is mentioned in the first verse of the university’s alma mater. Geography is one of UT’s distinctions. It could not be mistaken for any other campus. And in several obvious ways, it has formed UT’s distinctive culture.

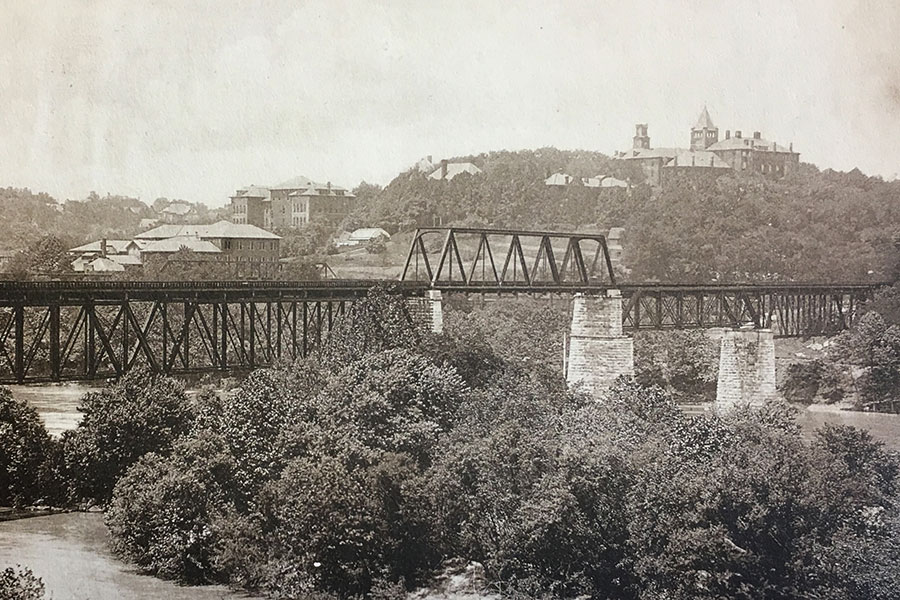

The Hill as seen from the river (circa 1900)

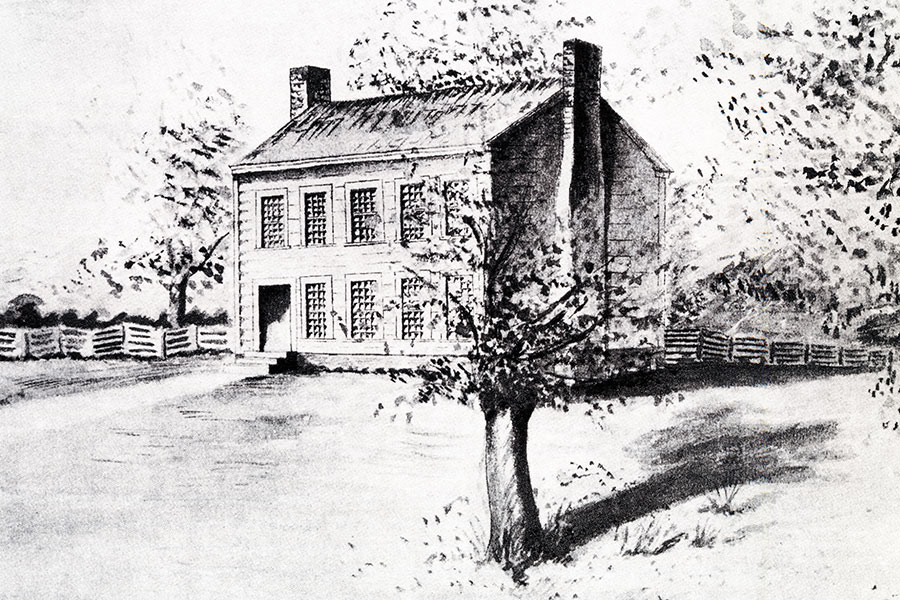

Blount College was founded in 1794 in a different place, not quite a mile to the northeast on a flattish plateau on the top of a river bluff, in what was rapidly developing as a capital city’s central business district. UT President Samuel Carrick’s first experiment in higher education was near the corner of what we now know as Gay Street and Clinch Avenue, the site of the current Tennessee Theatre. That college closed upon Carrick’s unexpected death in 1809. As it happens, his gravestone, still legible from the sidewalk, is just across State Street from that first campus.

Blount College (1794)

That site was limited in size for a growing college, and several years after Carrick’s death, the trustees of East Tennessee College chose to move it. It’s interesting to consider that the trustees might have remembered a bit of advice from former US President Thomas Jefferson, who recommended in an 1810 letter that this college in Tennessee—a state he never visited—should spread out a little to become “an academic village.” It was years before he founded his own academic village, the University of Virginia.

The summer that Jefferson died, in 1826, Knoxville’s trustees believed they had found a perfect site. It was on top of one of the steepest hills around, just west of what had been known to army recruits during the War of 1812 as Scuffletown Creek. Some people call it Barbara Hill, with the presumption that it was named for the daughter of William Blount, one of the first female students in Carrick’s school. (There’s evidence that that same name had previously been used for the friendlier hill closer to the river, the knoll that became the site of Circle Park.)

The trustees bought that 40 acres, citing its “two or three excellent springs” and the Hill itself: “the commanding view from it and to it in every direction, the excellence of the water, the distance from the town, being near and yet secluded, its position between the river and the main western road,” where everybody could see it (they were talking about publicity even then). Those advantages combined with an “unquestionable healthfulness render it a scite [sic] as eligible, almost, as the imagination can conceive.”

That Hill was extraordinarily steep, even for pioneer hill people. It says something that a graveyard established way up there in Knoxville’s early days was unvisited and forgotten before construction crews were startled to turn them up in 1826.

But to academics, it seemed a place to put a “City on a Hill”; to the classical minded, it was an Acropolis, an exalted spot for learning, far above the humdrum chaos of ordinary commerce and folly.

Its elevation is over 961 feet. If it’s not the highest peak in Knoxville, it may be the most dramatic. The fact that it’s more than 140 feet higher than the nearby Second Creek bottoms makes the contrast extreme by city standards.

You won’t find a steeper hill climb in the central part of Knoxville. If you start at the little park by the creek and climb to the top of the Hill, you’ll climb about 225 steps—more or less, depending on which route you take. That’s more than two thirds the climb to the top of the Statue of Liberty. Halfway up, you may feel you’re climbing along Incan pathways.

(The story that the Hill makes UT students look a little different from flat-campus students is a couple of generations old.)

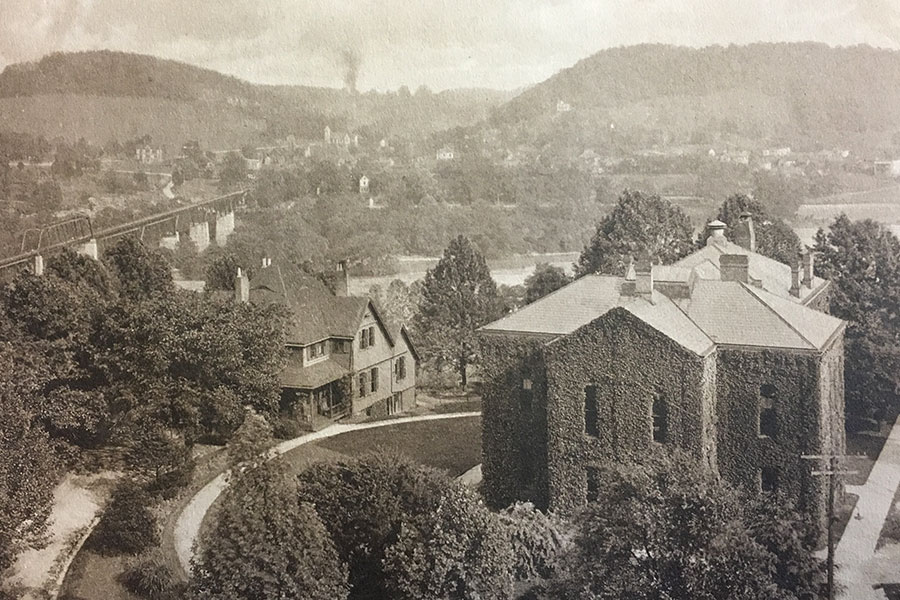

Carrick Hall on the right in 1912

Also unusual and influential is UT’s adjacency to a major river—and one with which it happens to share a name. The university owns a bit of Tennessee River shoreline, which appropriately includes a large boathouse for the competitive rowing team. And of course the riverfront location suggests wharfs for pleasure boats and the boaters who make up the game day group called the Vol Navy. UT’s football stadium is one of only a few in the nation so close to a navigable body of water.

But there are also two substantial creeks. Second Creek, which originates in northern Knox County, flows through Sharp’s Gap, almost five miles north of campus. It was known for railroad-related industry, but from about 1866 to 1909, Second Creek was the location of Knoxville’s best-known breweries, all just upstream from UT—as well as Knoxville’s iron works. Its valley hosted the first railroad to Cumberland Gap and, almost a century later, the 1982 World’s Fair.

On UT’s west side is Third Creek, which divides the main campus from the agricultural campus and runs through Tyson Park. It’s longer, more complicated, and more unpredictable than Second Creek. If you follow Third Creek upstream north, you’ll encounter a substantial prong making a sharp turn to the west to near Sequoyah Hills and Bearden. In fact, Papermill Drive was named for a 19th-century paper mill that was on Third Creek. Knoxville’s first airport, in the 1920s, was along the Third Creek floodplain. Follow it upstream, and it will take you a few miles north to Victor Ashe Park and Norwood, at the foot of Black Oak Ridge across the northernmost part of Knox County.

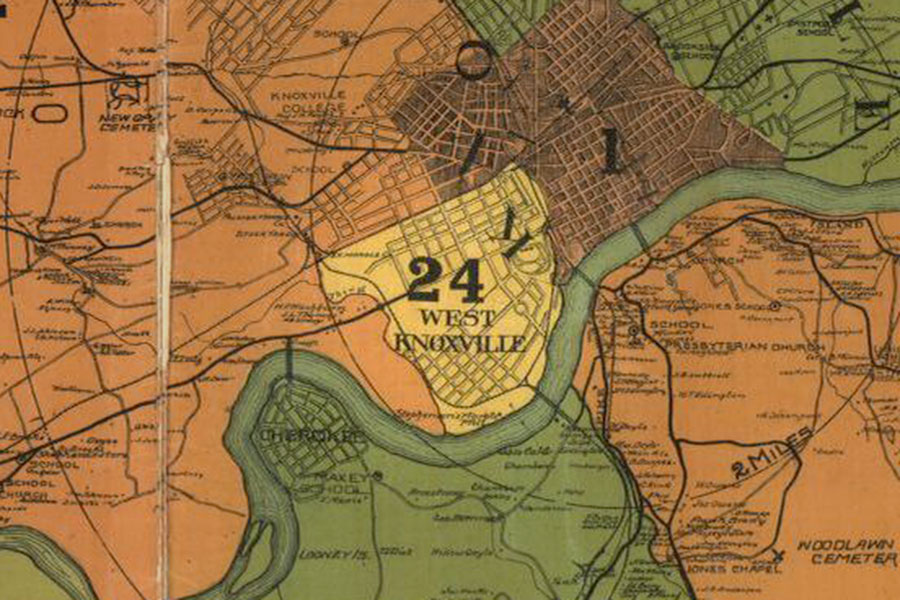

The two creeks that empty into the river on either side of campus drain a large industrial, residential, and partly rural area, perhaps 20 square miles, of North and near-West Knoxville.

UT’s peninsula would seem geographically notable, central to Knox County even if there weren’t a campus here. But as planners observed two centuries ago, it’s an eligible, and maybe perfect, place for a university.

UT Peninsula. Detail from 1895 Knox County map.

This story is part of the University of Tennessee’s 225th anniversary celebration. Volunteers light the way for others across Tennessee and throughout the world.

This story is part of the University of Tennessee’s 225th anniversary celebration. Volunteers light the way for others across Tennessee and throughout the world.

Learn more about UT’s 225th anniversary

4 comments

Very interesting about the history of UT.

“Like a Beacon shining Bright…..” VFL!

Jack Neely, you should put this in a book — I would buy one!

It is a beautiful dream come true of the pioneers of the young state of Tennessee. I spent 27 yrs there across the in JHB and owned a house next to the old library on White Ave where new Moss building has been erected now.

Comments are closed.