The year is 1931. Clark Gable watches as a young Joan Crawford sits behind a piano and begins to play. Her arresting, sharp features defined by MGM’s Max Factor draw in the audience, seizing attention as she opens her signature hunter’s bow lips to sing. The director zooms in, exploiting the actors’ chemistry. Audiences sit just as the film’s title suggests: Possessed.

In this, their third pairing, Gable and Crawford earn their titles as Hollywood royalty along with the kingmaker: director Clarence Brown.

Crawford later called the film “hardly original or significant” in her 1963 autobiography, A Portrait of Joan, but she said the director stood in juxtaposition. He was someone significant.

“A small man, professorial in appearance, he kept us geared to his slightest expression of approval or disapproval,” Crawford recalled. “Reserved, dignified, I’ve never known a director with more respect for each minute detail in each and every scene.”[ii]

Clarence Brown

Meticulous detail prevailed thanks to an engineer.

Clarence Brown, born May 10, 1890, spent his youth in East Tennessee, earning two engineering degrees from the University of Tennessee by the time he reached age 19. The six-time Academy Award nominee’s name remains well known at the university because of his eponymous theater dedicated in 1970, but Knoxville community members remember little about Brown’s career and legacy, both of which began on the hallowed Hill.

The Browns moved to Knoxville from Massachusetts around 1902. His mother learned to drive a horse and buggy at Circle Park. His father labored as general manager of Brookside Mills textile manufacturing company, then Knoxville’s largest employer, in North Knoxville near Holston Gases’ current site. And in his childhood, Brown occupied himself with trips to the Great Smoky Mountains, dramas, and literary readings. A circa 1900 flyer housed in the Clarence Brown Collection at UT shows “Master Clarence Leon Brown, Juvenile Entertainer” seated on a stool, sporting a silk smock and tight trousers. The advert promotes “tragedy, humor, pathos, dialect, wit, scenes and sketches” by the “dramatic reader, impersonator and imitator.”

Clarence Brown (ca. 1900)

Brown continued his affair with the arts at UT as a member of the Philomathesian Literary Society, one of two campus literary societies forced to publish underground in the 1880s and after as faculty and students debated campus press freedom.[iii] Though studious by nature, Brown found time for fun, even entertaining an affair with the daughter of university president Brown Ayres.[iv] In her 2018 book, “Hollywood’s Forgotten Master,” University College (Cork, Ireland) film history professor Gwenda Young details Brown’s young love during his engineering studies.

“While testing and monitoring furnaces . . . Brown also found time to stoke a little romance,” Young said. “[He] fell hard for Elizabeth Ayres . . . sweeping her off her feet with recitations of poetry and eloquent letters.”

Brown continued to woo women while working, eventually marrying five times. In his early career, he seemed to change passions as quickly as he later changed partners. After owning his own automobile dealership in Birmingham, Alabama, Brown realized another burgeoning industry would support his theatric passions and mechanical experience, one that would make him famous: cinema.

“Brown realized that if he were going to make it in the film industry, it would not be as an actor,” Young said. “He would gain entry in a much less showy fashion, by impressing a key figure with his knowledge of machines.”

Around 1915, Brown traveled north to work in silent films pioneered by immigrant filmmakers like Maurice Tourneur, a paragon of early moving picture producers and Brown’s mentor. Brown became a master in his own right under Tourneur’s tutelage, striking gold on the silent silver screen with Swedish actress Greta Garbo in the 1920s and ’30s.

“I never gave Garbo direction in anything louder than a whisper. Never had to,” Brown said in an interview for the Los Angeles Times. “It was something in her eyes, something behind them that could reach out and tell the audience what she was thinking.”[v]

Clarence Brown and Greta Garbo on the set of “Flesh and the Devil” (1926).

Shrouded in European mystique, Garbo captured art deco America’s sense of wonder under Brown’s artful direction. Despite his romanticism, Brown maintained his industrial tendencies.

“Brown may have been a remarkably sensitive director, but he came across as a typical American businessman,” British film historian Kevin Brownlow said, recalling a meeting with Brown in Paris. “At first glance, you’d take him for an oil tycoon.”

Brown kept a shrewd mind for business in a town and time when directors came a Depression dime a dozen. But Brown broke the mold; he took up the “business of showcasing stars,” spritzing them up like new cars he might place on a showroom floor for audiences and critics to adore.

Adore they did.

Brown gained fame working with the biggest names in Hollywood’s Golden Age: Garbo, Academy Award winner Norma Shearer, box office queen Crawford, “King of Hollywood” Gable, and John and Lionel Barrymore. Shearer garnered her third Oscar nomination for her performance in Brown’s 1931 film A Free Soul, going on to become the first person nominated for five Academy Awards for acting. Following his Academy Award win for his performance in the same film, Lionel Barrymore said the only decent thing he could have done was present it to Clarence Brown.”

Clarence Brown directing Greta Garbo and Robert Montgomery in “Inspiration” (1931).

Clarence Brown directing Joan Crawford and Clark Gable in “Chained” (1934).

Though Barrymore’s performance impressed the Academy, such theatrical performances failed to sway Brown. Ever the romantic, Brown favored raw, human performances and intimacy captured with cinema’s new technologies.

“They used to come on the set, those stage actors, and throw their voices up to the gallery,” Brown once recalled.[vi] “Whenever I had to direct a New York stage actor, I did an imitation of him. ‘This is how you’re playing it,’ I would say. ‘Is this how a human being behaves? You’re talking to me when you make a scene. It’s intimate. The camera is there, and I’m here, right beside it.’”

In 1936, Brown worked with Barrymore on The Gorgeous Hussy, a period picture about former President Andrew Jackson’s rise to political power and the women who influenced his prominence. Beulah Bondi’s backwoods charwoman portrayal of Rachel Jackson drew criticism from Tennesseans, reminding Brown of his origins and of the Tennessee Volunteers.

“He was happy to play host when the UT Volunteers football team visited Los Angeles in the late 1930s and again in the early 1940s,” Young said. “He helped drum up publicity for the games.”

The 1940s brought sporting activities to the forefront of Brown’s career as he directed National Velvet, a horseracing film starring a budding actress who The Nation reviewer and fellow Knoxvillian James Agee described as “rapturously beautiful”—12-year-old Elizabeth Taylor.[vii] The film, released Christmas day 1944, launched the American Film Institute’s seventh-Greatest Female Screen Legend to superstardom, where she would remain until her death in 2011.

“She could act, even in National Velvet,” Brown said. “Took direction better than most grown actresses. A pro all the way.”

Brown retired in 1953, having ushered in a new era of Hollywood talent. He remained in California with his fifth wife, Marian Ruth Spies, who encouraged him to reconnect with his alma mater. Her support and Brown’s pride resulted in $12 million for UT after his death in 1987 and the Clarence Brown Collection in the John C. Hodges Library Special Collections. Most importantly, his renewed interest in Tennessee led to the Clarence Brown Theatre’s inception—under Brown’s direction, of course.

“Brown wanted to be consulted on everything about the design of the building,” Young said, “its interior layout and even the type of seating.”

Clarence Brown Theatre’s website notes the venue served as one of the finest facilities in the nation and one of the showplaces of the UT Knoxville campus. Tennessee’s distinguished director alumnus fought for his vision in the theatre just as he fought to create stars and allow them to shine on screen.

“You had to fight for everything you got onto the screen,” Brown said. “That’s how things were set up with the old studio system, and it worked out for the best most of the time.”

“But you did have to fight. . . . Anything worth wanting is worth fighting for. Isn’t it?”

Clark Gable and Clarence Brown (1934)

Clarence Brown directing “A Woman of Affairs” (1929).

Brown died from kidney failure at age 97 on August 19, 1987. Fans and admirers now pay respects to the Hollywood pioneer at Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Glendale, California, the final resting place of America’s biggest stars like Humphrey Bogart, Lauren Bacall, Jimmy Stewart, Michael Jackson, and Walt Disney.

Brown’s legacy endures thanks to his gifts to the University of Tennessee and his films. Though some people may have forgotten Brown’s accolades, many remember the film giant just as actress Katherine Hepburn described him during the 1977 Directors Guild ceremony: “by nature highly romantic, by education an engineer.”

Sources:

[i] The title makes reference to a line from Brown’s 1941 film They Met in Bombay starring Rosalind Russell and Clark Gable. Russell’s character says to Gable’s, “Oh, darling. This has been the happiest time I’ve ever known in my whole roustabout career.”

[ii] Crawford goes on to say, “He was an engineer before he came to pictures and like an engineer he evaluated his tools and used them.”

[iii] Chi Delta and Philomathesian Societies published the University Monthly jointly beginning in 1875, a precursor to independent literary student media on campus, which now operates as the Phoenix Literary Art Magazine.

[iv] As in Ayres Hall, Brown Ayres.

[v] Quoted in “Clarence Brown, Director of Garbo, Gable, Dies at 97” by Ted Thackery Jr. of the Los Angeles Times, August 19, 1987.

[vi] Brown interview in Brownlow’s “The Parade’s Gone By . . .” (1976).

[vii] Agee writes, “She strikes me, however, if I may resort to conservative statement, as being rapturously beautiful.”

Photos courtesy of Special Collections, University of Tennessee Libraries

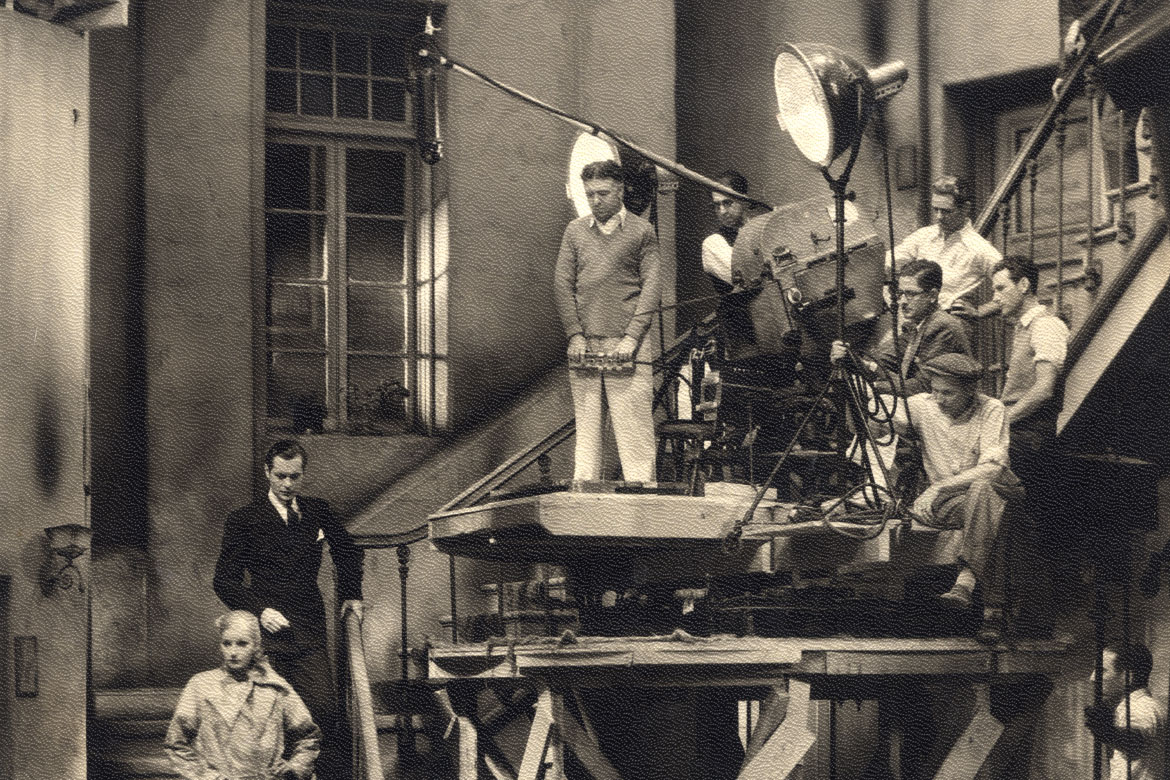

Top photo: Clarence Brown directing Gavin Gordon and Greta Garbo in Romance (1930). Clarence Brown Papers, MS.0702. Special Collections, University of Tennessee Libraries.

This story is part of the University of Tennessee’s 225th anniversary celebration. Volunteers light the way for others across Tennessee and throughout the world.

This story is part of the University of Tennessee’s 225th anniversary celebration. Volunteers light the way for others across Tennessee and throughout the world.

Learn more about UT’s 225th anniversary

3 comments

I just saw Brown’s film version of Faulkner’s “Intruder in the Dust” today and I was tremendously impressed with the film. For a man trained as an engineer Clarence Brown was wonderfully sensitive and artistic. I loved the film and the courage that it took to make in an era where Jim Crow laws still prevailed. It’s a real shame Mr. Brown is not better known today. I greatly enjoyed your essay and plan to read more about his career in my copy of “The Parades Gone By.” Thank you.

In top picture That is Garbo sitting at piano not Joan Crawford in the Movie Inspiration 1930 Director Clarence Brown and William Daniels on the camera 🎥

Hi Harriet! You are correct! The feature image on this page is Garbo. University Libraries tells me that this photo is: Clarence Brown directing Gavin Gordon and Greta Garbo in Romance (1930). However, the opening paragraph of the story is citing another movie in which Crawford is playing the piano, according to the story’s author. We will add a caption to the feature photo to make clear that it is Greta Garbo. Thank you for pointing out this coincidence!

Best,

Cassandra Sproles

Executive Editor

Comments are closed.