Just a short drive from UT’s campus and Knoxville’s paved streets and city lights, an outdoor expanse provides not only a radical change of scenery but unique educational opportunities for the university’s faculty and students. Though the Great Smoky Mountains National Park is the most-visited national park in the country, it’s much more than a recreational place. Home to more than 19,000 species of living organisms, the park is one of the most ecologically diverse places in the United States, making it a classroom like no other.

“I truly believe it provides us with a perfect setting for knowledge creation,” says Jennifer Schweitzer, professor of ecology and evolutionary biology.

Schweitzer is one of many UT professors using the national park as an outdoor classroom. Together with Joe Bailey, associate professor and chair of undergraduate affairs in the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Schweitzer has taught field ecology in the Smokies five times in the past decade.

Their class is an introduction to real-life scientific research. Groups of 24 students visit a field site, make observations, and identify three research projects. They have three weeks to collect data, process samples, and write papers with their findings. They formulate hypotheses and learn new techniques that help them address their scientific questions.

All that hard work has yielded benefits. “Our students have produced a total of seven papers that have been published in international journals,” says Schweitzer.

Exploring topics such as bee colonies, deer exclosure sites, and plant invasive species, their research is particularly valuable to the university’s mission as a land-grant institution.

Brian Alford agrees with that assessment. An assistant professor of forestry, wildlife, and fisheries in the Herbert College of Agriculture, he’s been taking undergraduate and graduate students to the park since 2014 to conduct research on restoration of native species.

Among their recent research work is a mussel survey in Abrams Creek and the current status of non-native trout as an invasive species.

“The knowledge we produce helps the park utilize resources in a more efficient way,” he says. He also organizes outreach efforts with students and volunteers, offering information sessions about the quality of the water in the park’s streams.

“The park is beautiful because a lot of its natural ecosystems are still intact and undisturbed. We want to educate people about it and, hopefully, convince them to help us keep it that way,” Alford says.

ENDLESS STORIES TO TELL

In some cases, students have a chance to spend the night at the biology field station in Pittman Center, an 18-acre research and teaching facility operated by UT’s Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology next to the Greenbrier entrance to the Smokies. Those who stay there get to experience nature in a unique way.

“The Smokies are the most diverse forest in North America,” says Gary McCracken, professor of evolutionary ecology and conservation biology. His class on the natural history of the Great Smoky Mountains is a three-week seminar that explores the geology, geography, and human history of the park. “My students love going on bat walks at night and birdwatching at dawn. We also track small mammals and investigate plant communities.”

Classes in which biology plays a main role, like those of Schweitzer, Bailey, and McCracken, are a natural fit to be held in the national park. But less obviously connected disciplines find a home there as well.

“The Smokies can be very inspiring for a writer,” says Mark Littmann, the Julia G. and Alfred G. Hill Chair of Excellence in Science, Technology, and Medical Writing.

Littmann has been teaching environmental writing in the College of Communication and Information for 25 years. With the park being so close, many of his students choose to feature it in their assignments.

“They portray the park’s diversity, research, challenges, and unsung heroes. There are endless stories to tell there,” he says.

In narrating these stories, students acquire experience as outreach agents, a vital role for the conservation of the park. “If the park is struggling, a good story can get people’s attention. Suddenly they care because they are informed,” Littmann says.

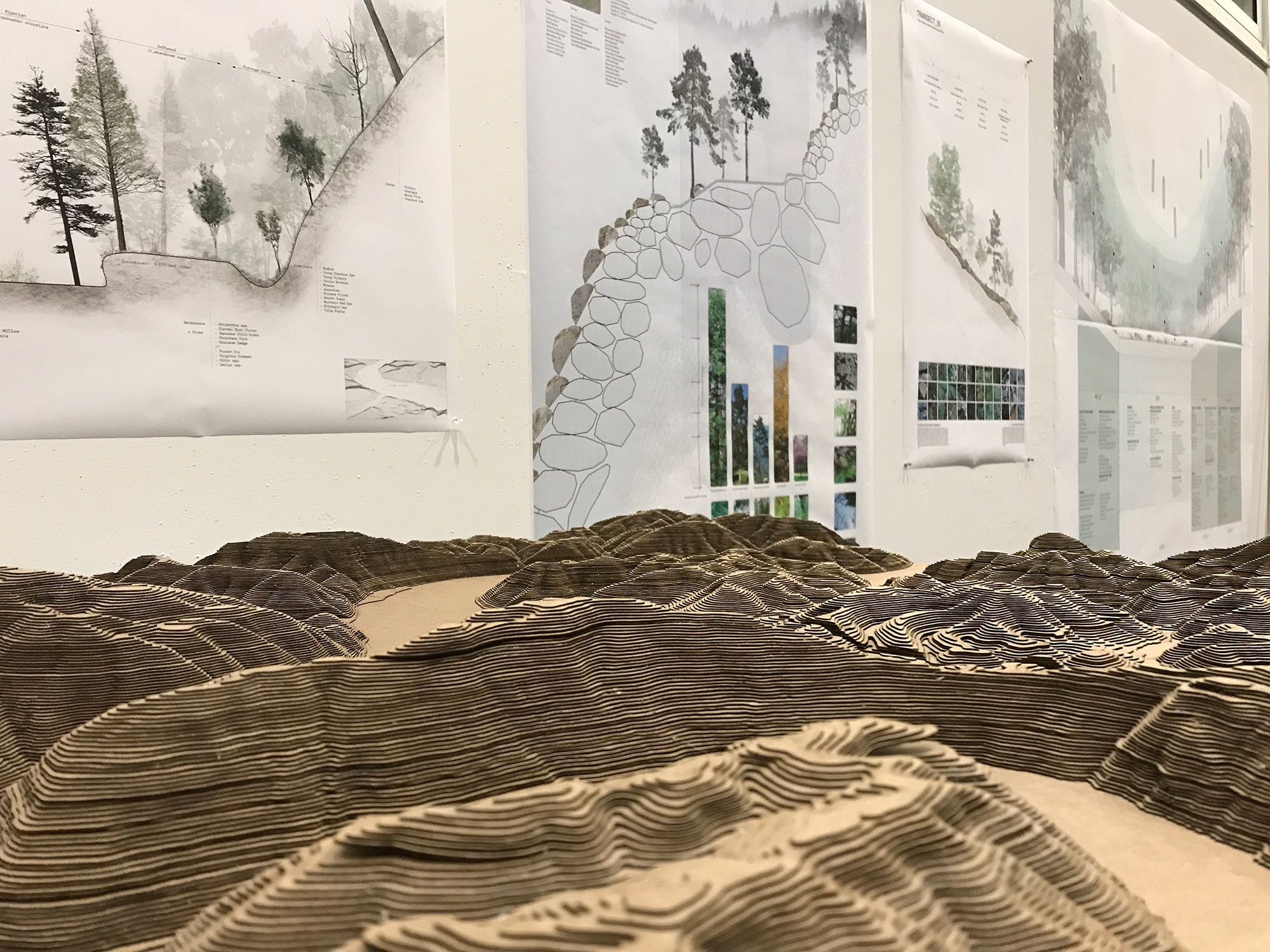

Endowed professors are also attracted to the park’s learning possibilities. In 2018, award-winning architect Billie Faircloth led the Great Smoky Mountains Studio, a workshop in which students from the College of Architecture and Design’s three schools—Architecture, Interior Architecture, and Landscape Architecture—developed three Smokies-inspired proposals: a center for ecological interpretation and land use history, a companion extraction landscape, and a material processing site.

“The studio was fully immersed in a design challenge that aimed to redefine the relationship between architecture, construction, ecology, and land-use change over time,” Faircloth says. “This was an ambitious, timely, and pressing challenge, one that provided insight into a necessary future for architectural practice and its practitioners.”

Faircloth is a partner in the Philadelphia-based architecture firm KieranTimberlake. Her time at UT was made possible by the BarberMcMurry Endowed Professorship, a $1 million endowment that promotes excellence in design taught by an internationally recognized architect, such as Faircloth.

Some projects have an immediate practical effect. In 2017, a team of students from three engineering departments worked together to help redesign and manufacture the park’s visitor donation boxes for Friends of the Smokies, a nonprofit group that helps fund a variety of projects in the park with donations. In the past, vandals were easily able to break into the less-secure boxes and steal donations—an especially harmful act since the park is one of only a few national parks that do not charge an entrance fee.

Jesse Johnson, a materials science and engineering student, told WBIR News, “All of us have a great love for the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. It’s one of our refuges where we go, so that alone was one of the best reasons we wanted to get on this project.”

To Schweitzer, the variety of UT classes is a testimony to the possibilities the park has to offer. “We take for granted our closeness to the park. We tend to complain that it is crowded and we wonder if it has any value,” she says. “And the answer is that it does: it has value as a training place for new scientists, architects, writers, and environmentally aware communities. There are still so many discoveries to be made in the Smokies, in so many fields. There are really important things to be learned. Until then, we will keep coming back.”

Great Smoky Mountains National Park

11.3 million visitors in 2016

1,300 miles of tributary rivers

730 miles of fish-bearing streams

400,000 hikers a year on 850 miles of backcountry trails

1,000 campsites

20+ active research permits for UT faculty and students

An Experience for Everyone

Part of UT’s noncredit offerings, the Smoky Mountain Field School serves as a bridge between the university and anyone eager to have an outdoor learning experience in the national park.

There are currently 32 courses scheduled for 2019. From hiking and monarch butterfly observation to campfire cooking and nature photography, the school has been offering experiences in the national park since 1978.

“The activities gave us an extensive appreciation for the history, the rich ecological diversity, the wildlife, how to use the park safely, and how to become an ambassador and advocate for the national park,” said Michele Smith, a participant in the Spirit of the Smokies Program.