As the COVID-19 pandemic became more prevalent in March 2020, the Tennessee Emergency Management Agency and the US Army Corps of Engineers began to prepare for the worst, evaluating areas on campus for use in the event that local hospitals became overwhelmed. Though these preparations have not been necessary, they are reminders of the role the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, has played in times of crisis throughout history.

Caught Between Both Sides in the Civil War

A view of the Hill at East Tennessee University during the Civil War

Tennessee seceded from the Union on June 8, 1861, the 11th and last state to do so. After the battle of Fishing Creek in Kentucky in January 1862, the buildings of East Tennessee University (UT’s name at the time) were used by Confederate soldiers to lodge the wounded. That spring, after most of the students joined the military—on both sides—the university trustees voted to suspend operations.

In September 1863, Union troops forced the Confederates out of Knoxville. On the Hill, the Union Army enclosed the three buildings in an earthen fortification they named Fort Byington in honor of an officer from Michigan who had been killed in the defense of Knoxville. They used the buildings as headquarters, barracks, and a hospital.

In late November, the Confederates tried to retake the city, the climax of which was a bloody attack on Fort Sanders on November 29, 1863. During the battle, the Hill was hit with artillery fire from Confederate guns located in a trench at the present-day site of Sorority Village. Nonetheless, the Union held and occupied Knoxville for the rest of the war.

After the war, the university reopened in 1866 and operated for six months downtown—at the current site of Lincoln Memorial University’s School of Law on West Summit Avenue—while campus repairs began.

On October 1, 1918, the UT training detachment merged into the Students’ Army Training Corps.

Training Officers for World War I

The United States entered World War I on May 17, 1917. An act of Congress had established the Students’ Army Training Corps (SATC) at some 550 colleges and universities to provide coursework to prepare college men for central officers’ training schools.

The SATC was divided into two sections: Section A was the academic unit, replacing the Reserve Officer Training Corps. Section B was the vocational unit, with the Department of Engineering providing training in auto mechanics and auto driving, radio operation, electrician training, machinist training, blacksmithing, bench work, general carpentry, sheet metal working, and welding.

Between April 15 and November 1, 1918, a total of 1,580 men—some of them UT students—received eight weeks of training. Many classes were in Estabrook Hall. UT converted Old College Hall (later torn down to make way for Ayres Hall) into a dormitory and built a large two-story barracks for 200 men. Jefferson Hall (no longer standing) was enclosed to serve as a dining hall. An unused school building housed 150 more men, and a vacated factory near the university was rented to accommodate the rest.

Turning the Tide in Battle

Lawrence Tyson, owner of Brookside Mills, had taught military science at UT in the 1890s, earned a UT law degree in 1894, and served as a colonel in the Spanish–American War. When the United States entered World War I, he returned to active duty and was appointed brigadier general over all Tennessee National Guard troops. When his commission was federalized by President Woodrow Wilson, Tyson was assigned to lead the 59th Brigade of the 30th Infantry Division and helped train them at Camp Sevier near Greenville, South Carolina. They embarked for France with the 30th Division in May 1918, and in July they were among the first American troops to enter Belgium.

In September, the 30th Division was ordered to the Somme area in northern France and positioned opposite the heavily fortified Cambrai-Saint Quentin Canal section of the Hindenburg Line. On the morning of September 29, the division attacked German fortifications along this section of the line, marching in dense fog, pushing across a three-mile stretch of wire entanglements and trench defenses before crossing the canal and securing the area. Tyson’s 59th was the first Allied brigade to break through the Hindenburg Line, sparking a victory that helped turn the tide of the war.

Sadly, on October 11, Tyson’s son Charles McGhee Tyson, a Navy pilot, was lost over the North Sea while scouting for mines. (In 1927, the Tysons gave the land on Sutherland Avenue for Knoxville’s first airport, which was named in McGhee in Tyson’s memory. Their home, originally donated to St. John’s Episcopal Church, is now the Tyson Alumni Center.)

On October 15, in northeastern France some 175 miles east of the Somme, Second Lieutenant Richard F. Kirkpatrick, a Knoxville native who had grown up on West Hill Avenue and graduated from UT in 1917, was killed by German fire amid the chaos of the Battle of the Argonne Forest. He was one of 12 alumni who died in the bloody Meuse–Argonne Offensive, part of the Hundred Day Offensive that brought the war to an end on November 11—a date that was celebrated as Armistice Day until it was renamed Veterans Day in 1954.

More than 2,500 UT alumni and students served on active duty during World War I, receiving more than 215 decorations. In all, 29 died in battle or in hospitals, and their names are enshrined on a plaque in Alumni Memorial Hall.

The original Reese Hall in 1920

The Flu Pandemic of 1918

The flu hit Knoxville in the fall of 1918. On October 9, 1918, the city Board of Health closed schools, churches, theaters, and pool rooms, and UT canceled classes. Some 9,500 of the city’s population of 75,000 got the sickness; 132 died from it.

Knoxville General Hospital was overwhelmed, and makeshift hospitals were set up for soldiers at Chilhowee Park and UT’s original Reese Hall. UT resumed classes in November, and the shortfall of hospital space during the outbreak hastened the construction of Fort Sanders Hospital in 1920. In 1937, UT razed Reese Hall, and a new dormitory with the same name opened in 1966.

Training and Bandage Rolling during World War II

In 1942, just a few months after the United States entered World War II, Eugenia Hamlett Curtis (’44) left her home in Ardmore, Tennessee, to become a student at UT. “I lived in Henson Hall,” she remembered. “Shortly after we moved in, we were transferred to Mattie Kain Dormitory [no longer standing] to make way for platoons of engineers and Air Force recruits who were training at UT. I still think about all those boys who went off to war.”

Like the rest of the country, UT mobilized for war after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. In January 1942, President James Hoskins established the UT Defense Council to coordinate various defense services and begin any needed new ones. All deans and directors and the president of the student body were members.

Beginning in 1939, UT had participated in the Civilian Pilot Training program, trained College of Home Economics students to serve as volunteer nurses in a project sponsored by the American Red Cross, and carried out extensive agricultural defense activities. The UT Agricultural Extension Service was designated by the national, state, and county agricultural defense boards to lead the educational phases of all programs.

A Volunteer Yearbook photo spread of training during World War II

Starting in 1942, Mortarboard, the senior honor society, sponsored a Red Cross Bandage Room in the library (named Hoskins Library in 1950). In 1943, the Red Cross established a unit at Tyson House for faculty wives and townswomen to make surgical dressings.

In spring 1943, Nathan W. Dougherty, who was coordinating training efforts for military personnel on campus, received a call asking for housing and instruction in civil, mechanical, and electrical engineering for some 300 draftees for the Army Specialized Training Program (ASTP). One hundred ninety enlisted service members arrived in November 1943. Since the residence halls were already committed to cadets training for the Army Air Corps, UT placed ASTP students in fraternity houses until it was able to acquire Tennessee Valley Authority barracks, which the ASTP students moved into in January 1944. A second cycle of some 25 ASTP students arrived in February 1944. One ASTP mechanical engineering student was Kurt Vonnegut Jr., who was captured by the Germans during the Battle of the Bulge and wrote about his experiences as a prisoner of war in the modern classic Slaughterhouse Five. The Army discontinued the program on March 25, 1944, in order to redirect participants to be trained as ground troops for European campaigns.

More than 6,800 UT men and women served in the armed forces during World War II; 954 received citations for bravery and exemplary service, and 315 lost their lives.

After World War II—Housing Returning Soldiers

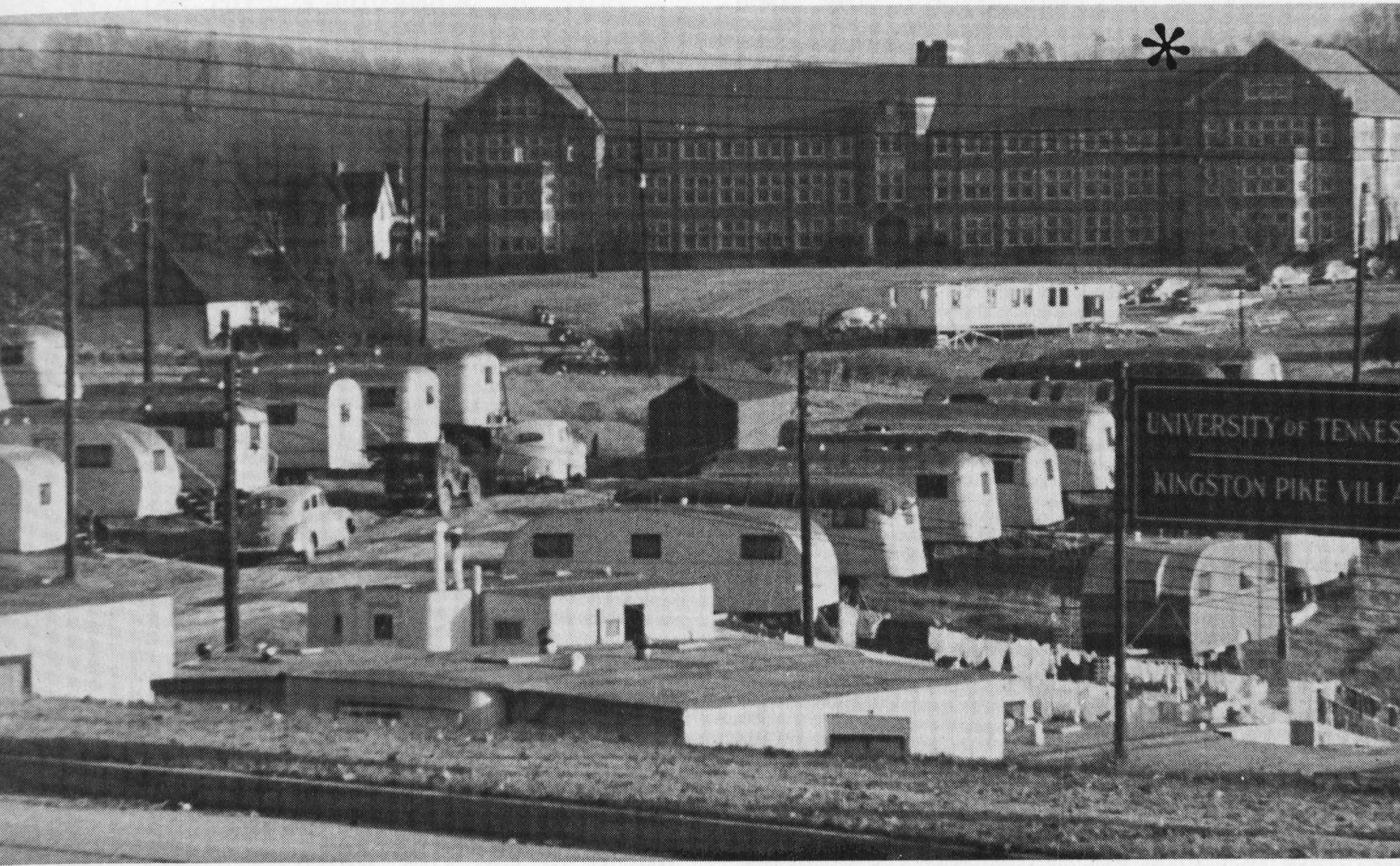

After WWII, UT established Kingston Pike Village on the agricultural campus. The trailers were across the street from Morgan Hall.

Between 1945 and 1949, UT enrollment quadrupled with returning veterans taking advantage of the GI Bill, creating a need for extra housing for students, classroom space, and facilities.

To meet the housing demand for veterans attending the university and their families, trailers were placed on the lawns of the Hill. Hillside Village, on the east side of the Hill where Dougherty Engineering now stands, grew to 75 trailers and included community laundries and bath houses—one for every 25 trailers.

Housing for 485 single students was provided by barracks-type structures—some built by UT and some relocated from Camp Crossville, a prisoner of war camp. One was west of Austin Peay, one where the College of Law complex is now located, and a third at the current site of the Haslam Business Building. Barracks from Camp Crossville were also moved to the Sutherland Avenue land that had been the first McGhee Tyson Airport (and are now RecSports fields). The program also placed three groups of housing barracks on campus—on Cumberland Avenue, on the Hill, and on the agriculture campus.

Some 125 trailers were moved from Oak Ridge, where they had provided housing for scientists during the development of the atomic bomb, to house married students. They were placed along Kingston Pike at the agriculture campus as Kingston Pike Village, next to the home of former UT President Harcourt Morgan, then a TVA director. Since they had neither wheels nor axles, they were lifted by cranes onto trucks and then onto foundations built by 32 members of the Vol Veterans Club and 40 employees of contractor Dykes and Gerhardt. All were connected for water and sewer service.

The trailers on Hillside Village began to be removed in 1950 when repairs became uneconomical. The final eight families living in the village at the close of winter quarter 1951 were relocated either to Kingston Pike Village or Sutherland Avenue.

Prefabricated structures from Camp Forrest, a prisoner of war camp in Tullahoma, Tennessee, were placed on the Hill and used as classrooms, labs, and offices. These structures and their installations were financed by the Federal Works Agency under the GI training program.The structure behind Ayres Hall was L-shaped and contained 32 offices, which were occupied by faculty members in business, education, and liberal arts. A three-unit chemistry building that contained 18 classrooms was located in the back of Science Hall (no longer standing) and across from Ferris Hall. The Chemistry Annex, also known as Splinter Hall, was used for chemistry classes until the 1954 addition to Dabney Hall was completed and then by music until a new music building opened in January 1966. The annex was still in use by psychology and continuing education until it burned in 1972.

Structures from Camp Forrest were also placed on the agricultural campus: a veterinary clinic, two laboratory buildings, a lunchroom cafeteria (Mabel’s), a blacksmith shop, and a bull barn on Cherokee Farm.

Reed and Loise Hogan in 1949

The Christian associations, which provided a partial student center function, were located in a barracks until they moved to the Carolyn P. Brown Memorial University Center at the site of the current Student Union. The student newspaper and yearbook were also located in this barracks.

Reed Hogan (’49), a Pacific battle veteran with the Marine special operations unit Carlson’s Raiders, and his wife, Loise Culp Hogan (’49), who had been a Naval Intelligence decoder, were among the thousands of veterans at UT.

A highlight of their time together was going to football games—sitting separately in the male and female sections. “There weren’t many married couples attending the same class,” said Loise on her recent 100th birthday. “When we were in the same class, we always competed to see who could get the best grades. Sometimes the instructors kidded around with us in class about that.”

In the intervening years, campus has weathered events on a smaller scale.

Meeting the Challenge of COVID-19

Even though classes went online and campus has been empty during the COVID-19 pandemic, Volunteers have stepped up during this time—making face shields for health care workers; donating protective gear and lab materials to medical facilities, raising money for students needing emergency funds, providing online tutoring support to support academic success, and delivering groceries to neighbors—to show support for one another near and far. Meanwhile other alumni and students have done essential work in hospitals and providing other needed services—on the front lines, just as they always have.

This story is part of the University of Tennessee’s 225th anniversary year. Volunteers light the way for others across Tennessee and throughout the world.

This story is part of the University of Tennessee’s 225th anniversary year. Volunteers light the way for others across Tennessee and throughout the world.

Learn more about UT’s 225th anniversary

5 comments

Proud of our Veterans. God Bless all Volunteers!

Great article! Born in Oak Ridge and grew up in Tullahoma, I am pleased that what these two small- town, Tennessee gems played and how they continue to have a huge role in the phenomenal work that UT is doing locally, nationally and globally. And, as the VERY proud daughter of a girl from 2013 bestseller, “The Girls of Atomic City”, my Mom, Jane Greer Puckett class of ’43 (August), lived 4 to a room in Strong Hall and was one of the student math and physics instructors to the ASTP soldiers as highlighted is this article.

Very informative and well-written article. I think you have covered every single point. I learned many new things. Thanks

Good Point !

NicE!