One of the ironies of American culture is that, repeatedly, the South becomes known for its devotion to things it first resisted. As strange as it may seem, the South was once skeptical of organized religion, automobiles, and the Republican Party—which, at various times, seemed to be impositions from the North. But then, after resisting these imports, the South embraced them to a greater degree than the rest of the nation, even to the extent that they became definitive Southern traits.

College football follows that pattern.

Football started in the Ivy League Northeast, and through the 1880s, was a distinctively, stereotypically Northern pursuit. At a Knoxville garden party in the 1880s expressing an interest in football was a way to brag that you’d been to New York or Boston recently, and that you were probably wealthy. It had evolved by degrees from a game known in Europe by the same name, which Americans call soccer. Before it arrived as American football, it went through a stage called rugby.

Rugby was named for England’s Rugby School, where the sport evolved. Americans first heard of the peculiar sport in an extremely popular novel by British author Thomas Hughes called Tom Brown’s Schooldays, first published in 1857. Chances are, your great-great-grandfather read it. If you have lots of heirloom books in your attic, I bet you’ll find a copy. Chapter 5 of this book, well-known by the time of the Civil War, is “Rugby and Football.” It describes a warlike game that involves running with an oblong ball, and it introduced a few terms new to Americans, punt and kickoff, and describes an innovation not part of the original game of soccer—the idea of kicking the oblong ball over a lofty bar for a score.

Of course the word rugby resonates in Tennessee. In 1880, long after he wrote the book that was still in print in America, the novelist cofounded a town called Rugby in Morgan County, Tennessee. Profits from his best-seller helped Hughes purchase hundreds of acres for what was originally intended to be a utopian community for England’s unlanded gentry.

The famous author and former member of Parliament came to Tennessee several times, sometimes visiting the Knoxville home of Rugby’s attorney, Oliver Perry Temple. That name is known at UT because Temple was one of the university’s most vigorous and influential trustees. The eastern part of what we know as Volunteer Boulevard was once named Temple Avenue.

In September 1880, Hughes spent two days in Knoxville, apparently at Temple’s downtown home. Receiving an extravagant welcome at the train station, he was here to promote his rugged Cumberland community just two weeks before its grand opening. Included was a posh luncheon at the Cumberland Avenue mansion of James Cowan, near what’s now 16th Street. (The Gardener’s Cottage, now a restored UT building at the corner of White Avenue, was part of Cowan’s backyard.) On prominent display at a central spot at the party was a copy of Hughes’s famous novel—the one with the section about rugby football.

Several UT supporters were part of the party. O.P. Temple hosted the dinner for Hughes that evening, inviting UT President Thomas Humes.

Did Hughes say to UT’s leaders, “You know, chaps, you should really try this game of rugby football”? We don’t know what they discussed. But how many NCAA campuses can claim they were visited by the early popularizer of a football-like sport?

We do have some evidence that Mr. Hughes’s favorite sport was a favorite of Knoxville’s Irish-immigrant community by the early 1880s. According to one memory, at least, rugby was played by Irish on a makeshift field by the train tracks downtown at Depot and Central.

By the late 1880s, American versions of football were well established in the Northeast, suddenly trendy on the West Coast, and catching on in the Midwest. Most of the South tried to ignore this Yankee impertinence. Knoxville’s earliest sports pages covered baseball, boxing, and horse racing.

Whether we were ready or not, the new sport began closing in from several angles.

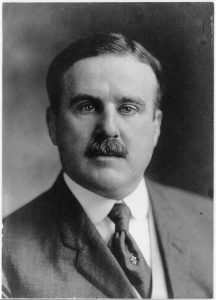

Lee McClung

One of American football’s first national heroes drew local attention. Knoxville native Lee McClung was halfback and captain of the Yale football teams that won the national championships. Even if he didn’t attend UT, McClung had connections on the Hill. One of his ancestors was among UT’s founding trustees. His older brother, Frank, was a UT baseball star in the 1870s, back when UT’s color was red. Decades later, his sister cofounded UT’s McClung Museum, which was named after their father. (Generations later, McClung’s younger cousin, Ellen McClung Berry, made the donation that built McClung Tower.) From 1888 to 1891, McClung and Yale established records so astonishing—McClung may be the highest scorer in college-football history—that even the stodgy, football-illiterate hometown press occasionally took notice.

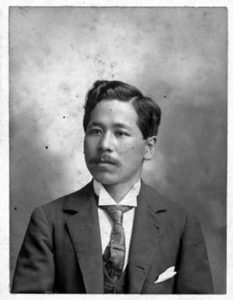

Kin Takahashi

At the same time, several miles to the south of campus, came an even unlikelier development. A Japanese student at Maryville College named Kin Takahashi put together a modern football team, probably the first one in East Tennessee. He’d picked up the American sport during a year in school in the San Francisco Bay area. Naturally, Maryville started looking around for other colleges to play against, and some UT boys began to feel the itch.

By then, word was getting around, and some town teams were popping up here and there. Knoxville had one, working at least occasionally with McClung. Even the new town of Harriman, a town that had strong Northern-industrial influences, had a team like Knoxville’s made up partly of Ivy League alumni.

UT finally fielded a team in the fall of 1891, organized just in time to play one game near the end of the season that resulted in a loss to Sewanee. It was Sewanee’s second game ever and its only win in a three-game season in which they lost to Vanderbilt twice.

If it wasn’t impressive, it’s proof that football did arrive at UT a bit earlier than in most Southern colleges, if just a few weeks before it got to Georgia, Auburn, and Alabama.

But Tennessee’s second game, and first win, was against Takahashi’s Scots in the 1892 season. It was the only season when UT lost to Sewanee twice—and to Vanderbilt twice. There weren’t many teams in Tennessee and no rules against playing one of them twice.

It was not early, but not terribly late, in the history of American football—though it was a long time before there were many spectators who weren’t personal friends of the players.

That’s the very beginning, what we might consider the prehistory of Volmania, and it’s hard to prove its association with what happened 35 years later.

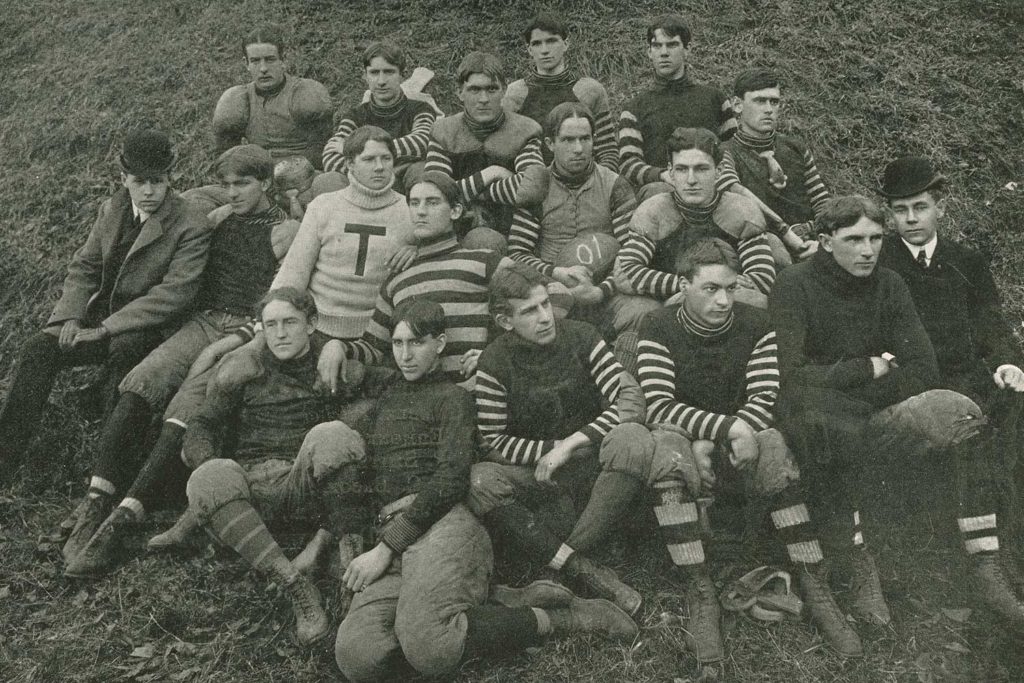

University of Tennessee Football team, 1896

University of Tennessee Football team, 1902

By 1900, most universities had football teams, and UT did, too, though it didn’t prioritize the game. The campus didn’t even have a regulation field until 1921.

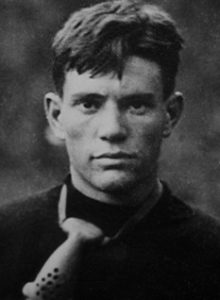

They sometimes did well, sometimes didn’t. Most folks didn’t care much. Attendance was sometimes in the hundreds, rarely in the thousands, and overwhelmingly dominated by students and recent alumni, especially fraternity brothers and girlfriends of the players. One of the few teams that got much attention starred engineering student Nathan Dougherty. Born in a log cabin in Virginia, Dougherty was a standout for UT’s 1907–08 teams and drew some new attention to the game, at least when he was playing. But his greatest inspiration to UT’s football tradition was yet to come.

Nathan Dougherty

By the early days of radio and movies, most Tennesseans had still never seen a football game. Industrial-league baseball was more popular. The Vols games were played on old Wait Field, a rocky, slopey patch right by Cumberland Avenue.

Volmania, the term, dates to the Dickey years of the mid-1960s, but the concept became obvious about 40 years earlier. What created Volmania came in the form of a former doughboy and Army captain from West Point.

Robert Neyland was born in northeastern Texas in 1892, a few weeks after Lee McClung’s last championship season at Yale. Drawn to the military, he earned a place at West Point and was a lineman for the Black Knights for three seasons. He graduated the year before his country entered World War I. He served as an officer in France, and as a combat veteran in his 20s, he served as an aide to the impressive but not-yet-legendary General Douglas MacArthur at West Point, eventually helping to coach the Army’s football team.

He became fascinated with the strategy of the game. But when Dougherty, the former football star, now a UT engineering professor and athletic chairman, first contacted Neyland, it was to interview him for the job of ROTC director with some side duties as an assistant coach.

In a short time, Neyland found himself in the driver’s seat and instantly began turning in winning seasons with a curious new strategy emphasizing defense over all other aspects of the game. Some date the birth of Volmania to his third season—specifically October 20 and November 17, 1928, the days Neyland’s Vols beat regional powerhouses Alabama and Vanderbilt, respectively, both in enemy territory.

General Robert Neyland

Neyland’s success stood out in even sharper contrast considering that during his glory years, East Tennessee and Knoxville in particular began getting some horrible press, as the city was described by one writer as the world’s dirtiest city, by another as America’s ugliest city, and yet another as one of the nation’s most sinful cities. Factories were closing, politicians were corrupt, the air was so dirty that businessmen had to change their white shirts at lunchtime. But at least we had the amazing Vols.

People who weren’t UT students and alumni, even people who’d never been to college at all and who hadn’t even quite learned the rules yet, started getting interested in attending games. In the 20 years after that 1928 season, the stadium, which was hardly distinguishable from high school bleachers when Neyland arrived, had septupled in size, to accommodate almost 50,000.

And, as you know, it didn’t stop there.

This story is part of the University of Tennessee’s 225th anniversary celebration. Volunteers light the way for others across Tennessee and throughout the world.

This story is part of the University of Tennessee’s 225th anniversary celebration. Volunteers light the way for others across Tennessee and throughout the world.

Learn more about UT’s 225th anniversary

1 comment

Always interested in UT news as I was a student there.